As Choice as Could Be:

Eric Gill, Harry Graf Kessler,

and The Cranach Press’s

Canticum canticorum Salomonis

Tracy C. Bergstrom

The Cranach Press’s Canticum canticorum Salomonis represents a high-

light in the history of modern book design and fine press printing;

the volume’s unusual format, combined with Eric Gill’s illustrations

and the use of Jenson antiqua type, create a striking and memo-

rable work. The publication of Canticum canticorum Salomonis also

marked a turning point in the working relationship between Gil

and the publisher of the Cranach Press, Harry Graf Kessler. Although

Kessler has been previously portrayed in scholarly publication as

the dominating force behind Canticum canticorum Salomonis, a close

examination of their personal correspondence and interactions

reveals that Gill increasingly began to assert artistic independence

in their collaboration and determined many significant aspects of the

volume’s style. Gill’s long-standing interest in the text of the “Song

of Songs” and its mixture of eroticism and spirituality, combined

with his desire to experiment with method and technique, resulted

in a project for which Gill guided the selection of text, illustration

program, and salient aspects of the book’s production.

The perception that Kessler firmly directed all creative

production of his Press artists and coaxed them into producing supe-

rior work originates with Weimar-era publications—most notably,

Rudolph Alexander Schröder’s influential 1931 assessment of the

Press’s output, “Die Cranach-Presse in Weimar.”1 Schröder claims

that Kessler’s varied intellectual ventures prepared him to guide

the work of individual artists toward his desired ends. In an exami-

nation of the typefaces designed for the Cranach Press by Emery

Walker and Edward Johnston, for instance, Schröder mentions

Kessler’s work as a student of Wil iam Morris and as the publisher

of the Art Nouveau journal, Pan, as experiences that provided him

with the artistic vision and clarity to direct the activities of Walker

and Johnston. The success of these typefaces can thus be attrib-

uted to Kessler’s oversight, in that “their rich diversity provides a

1 Rudolph Alexander Schröder, “Die

suitable foundation for the freedom and wealth of expression that

Cranach-Presse in Weimar,” Imprimatur:

are the distinguishing characteristics of all of Kessler’s prints.”2 In

Ein Jahrbuch für Bücherfreunde, (1931)

91-112.

2 Ibid., 94.

© 2011 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

3

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

Schröder’s narrative, this relationship exists not only with Walker,

Johnson, and Gill, but with all artists Kessler employed to work on

Cranach Press publications. He claims about Aristide Maillol that:

One need only remember that Maillol, the sculptor,

would probably never have emerged as the erudite and

satisfying illustrator and graphic artist whom we know

from his magnificent prints of Virgil’s Eclogues if the

founder of the Cranach Press had not encouraged him

and provided him with both a goal and clarification of

what the occasion demanded.3

Schröder’s assessment of Kessler as a master manipulator perme-

ates scholarship to the present day, as seen in Laird M. Easton’s

recent biography, The Red Count: the life and times of Harry Kessler.4

Regarding the Cranach Press’s 1926 publication, The Eclogues of

Virgil, Easton writes:

Years of patient, tenacious prodding on the part of Kessler,

gently but firmly shepherding such temperamental egos

as Maillol, Gill, the calligrapher Edward Johnston, the

letter-cutter Edward Prince, the printer Emery Walker, and

others toward the goal he had in mind, resulted in one of

the most striking printed books of the twentieth century.5

The first major book-length survey of the Cranach Press,

published by Renate Müller-Krumbach in 1969, reinforced the

notion that Kessler maintained tight control over salient artistic deci-

sions pertaining to successful publications of the press but added

explicit criticism of Gill’s involvement.6 In her analysis of Canticum

canticorum Salomonis, Müller-Krumbach compliments the aspects of

the publication overseen by Kessler, writing that the “dimensions,

binding, typeface and layout of the Song of Songs give the impression

of an exquisite bibliophile treasure.”7 Her assessment of Gill’s

contributions to the volume is not so charitable, however: “Gill’s

ornamented initials and his illustrations seem a poor fit in this

context.”8 The argument centers on the assertion that Gill’s illustra-

tions failed within the volume because they deviated from Kessler’s

specifications:

[The illustrations] are, in contrast to all previous principles

of the Cranach Press, neither linear nor flat, but plastic and

3 Ibid., 102-3.

three-dimensional, and thus serve as opposition and coun-

4 Laird M. Easton, The Red Count: The life

terpoint to the typography rather than as its complement.

and times of Harry Kessler (Berkeley: The

Velvety black areas in which the color white is largely

University of California Press, 2002).

5 Ibid., 371.

absent have been printed above a dark brown ground.

6 Renate Müller-Krumbach, Harry

White is used only to trace the contours which, since they

Graf Kessler und die Cranach-Presse

are composed of very fine cross hatching, do not mark

in Weimar (Hamburg: Maximilian-

continuous lines but rather produce a luminous iridescence.

Gesellschaft, 1969).

7 Ibid., 63.

8 Ibid.

4

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

This technique, which imitates ones more properly found in

engravings, does not meet Kessler’s original demands for

woodcut illustrations…. It remains surprising that Kessler

had these illustrations printed at such great expense…9

More recently, John Dieter Brinks’s essay, “In search of sensu-

ality: Kessler’s and Gill’s Songs of Songs,” is effusive in its praise of

the volume but seeks to establish that Kessler dictated all aspects

of Gill’s work and was thereby responsible for its success.10 Brinks

establishes the theme early on in the essay, writing:

When Eric Gill later looked back on his life he would attest

to what he had already known at the age of forty-three: that

the course of his life, both aesthetically and materially, was

in many ways connected to Kessler’s and that it was he

who had given him a vital impetus.11

In the section of the essay titled “Kessler’s Conception of the Book,”

Brinks lays out five specifications that Kessler purportedly dictated

to Gill to guide him in his work: the book’s physical dimensions, the

use of color in the illustrations, the gilding of the illustrations, the

dramatization of the text, and the shading of the illustrations.12 All

of these characteristics are present in correspondence between the

two, and all except the physical dimensions would evolve through

Gill’s independent work from Kessler’s original conception of the

volume, as preserved in his working notes.13

This present essay seeks to reexamine these perceptions

concerning Kessler and Gill’s relationship and working processes.

Their correspondence and individual diary entries document that

Kessler was quick to accept Gill’s changes in direction for the project

and that their relationship was a much more egalitarian one than is

suggested by previous critics. While their correspondence does show

that Gill’s illustrations did not follow Kessler’s initial specifications

for the project, it also records that Kessler was extremely pleased

with the images and their context within the publication. A review

of archival evidence also demonstrates that Gill exerted substantial

control over many aspects of the publication, including its textual

9 Ibid., 64.

10 John Dieter Brinks, “In Search of

contents, and that his decisions outside Kessler’s recommendations

Sensuality: Kessler’s and Gill’s Song of

led to the book’s critical acclaim.

Songs,” The Book as a Work of Art: The

The story of how Gill and Kessler decided on the “Song of

Cranach Press of Count Harry Kessler

Songs” for a Cranach Press publication is frequently recounted.

(Laubach: Triton, 2005), 146-67.

Kessler records in his diary that the two were together at Goupil

11 Ibid., 148.

12 Ibid., 152-4.

Gal ery in March 1925 to view Gil ’s statue of a sleeping Christ when

13 See the page from Kessler’s notebook

Kessler asked if Gill would be interested in illustrating a Cranach

reproduced in Brinks, “In Search of

Press volume. Gill replied that he would be pleased to create a set of

Sensuality: Kessler’s and Gill’s Song of

illustrations for a Latin edition of the “Song of Songs” or, alternately,

Songs,” 153.

illustrations to “Ananga-Ranga,” whose text he described to Kessler

14 Harry Graf Kessler, Tagebuch, March 13,

as “well, in reality: thirty-four ways of doing it.”14 Kessler wisely

1925, Deutsches Literaturarchiv,

Schiller-Nationalmuseum.

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

5

chose to pursue the first option. The informality of this exchange,

however, belies the pragmatic nature of their long relationship lead-

ing up to the project. The two were introduced in the spring of 1904,

and their first meeting occurred on September 7, 1904, according to

Gill’s diary.15 Their initial correspondence established a relationship

of Gill as contract worker and Kessler as artistic and financial advi-

sor. As early as 1908, Gill was advanced money from Insel-Verlag zu

Leipzig at Kessler’s request, in the hope that “your ancient pleasure

for working will return and that this will induce you to fill our orders

before others.”16 Their relationship took a preliminary turn in January

1910 when Kessler arranged for Gill to work as an apprentice to

Aristide Maillol in Marly-le-Roi; Gill, however, was uncomfortable

with the idea of apprenticing to someone with whom he spoke no

common language and who was located far from his residence in

Ditchling, and he backed out at the last minute.17 Kessler’s response

to Gill regarding the incident was cool, as he reiterated his belief that

Gill would have benefitted from Maillol’s experience, but Kessler

nonetheless also had to recognize Gill as a more independent and

willful artist than he had previously perceived.18 The overall tone of

their correspondence evolved to show a more equitable relationship

after this incident, with Kessler’s inclusion of Gill on major projects

in the next few years, such as his proposed Nietzsche memorial.

By the time of their joint work for the Cranach Press, Gill

had developed into a mature artist of great experience, including

previous publications and illustrations of the “Song of Songs.” Gill’s

interest in the “Song of Songs” bridged several decades. He first

published his thoughts on the text in an essay titled, “The Song of

Solomon and Such-like Songs,” which spanned several issues of The

Game in 1921. This essay was revised and published at St. Dominic’s

Press as an independent publication in 1921, under the title, Songs

Without Clothes: Being a Dissertation on the Song of Solomon and Such-

15 Eric Gill, Diary, September 7, 1904,

like Songs; it was further revised and published under the same title

M. S. Gill, William Andrews Clark

in Art-nonsense and Other Essays in 1929. In the essay’s introduction,

Memorial Library, University of California

Gill claims that, “the Song of Solomon is a love song, and one of a

at Los Angeles.

very outspoken kind, and in modern England such things are not

16 Insel-Verlag zu Leipzig to Eric Gill, March

considered polite.”19 Thus, Gill’s attraction to the eroticism of the

30, 1908, typescript letter with second

page missing, box 93, folder 9, M. S. Gill,

text and its interpretive potential was manifest, and makes his 1925

William Andrews Clark Memorial Library,

offer to Kessler of illustrating either the “Song of Songs” or “Ananga-

University of California at Los Angeles.

Ranga” less incongruent than it initial y appeared. The essay contin-

17 Eric Gill, Autobiography (New York:

ues with Gill’s thoughts on the intrinsically religious nature of the

Devin-Adair, 1941), 178-82.

“Song of Songs,” providing Gill with a platform to develop his

18 Harry Graf Kessler to Eric Gill, January

beliefs on the symbiotic nature of sexuality and spirituality:

24, 1910, box 93, folder 9, M. S. Gill,

William Andrews Clark Memorial Library,

But everything is religious by which God is praised, and

University of California at Los Angeles.

in this sense the Song of Solomon is a religious poem indeed.

19 Eric Gill, Songs Without Clothes: Being a

Not only is God praised in it, and by it, but His praises are

Dissertation on the Song of Solomon and

Such-like Songs (Ditchling: St. Dominic’s

Press, 1921).

20 Ibid., 3.

6

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

sung in the strongest of all symbolic terms. The love of man

and woman is made the symbol of God’s love for man, and

of Christ’s love for the Church.20

These principles, expressed in numerous other writings by Gill,

had been in formation for some time and also manifested them-

selves visually in the 1925 Golden Cockerel Press publication, The

Song of Songs: Called by many the Canticle of canticles. [see Figure 1]

One source for Gill’s initial artistic interest in the “Song of Songs”

may be a manuscript prepared by Edward Johnston. This vellum

model contains portions of the “Song of Songs” text, arranged and

hand-lettered by Johnston.21 Of the five passages from the “Song of

Songs” selected by Johnston, portions of three were later included

and illustrated by Gill in either his Golden Cockerel Press or his

Cranach Press treatments of the text. Johnson and Gill had enjoyed

a close relationship since their time as roommates in 1902-03, and

their influence on one another continued throughout the next

two decades.22

Critics have argued that Gill wished to illustrate the “Song

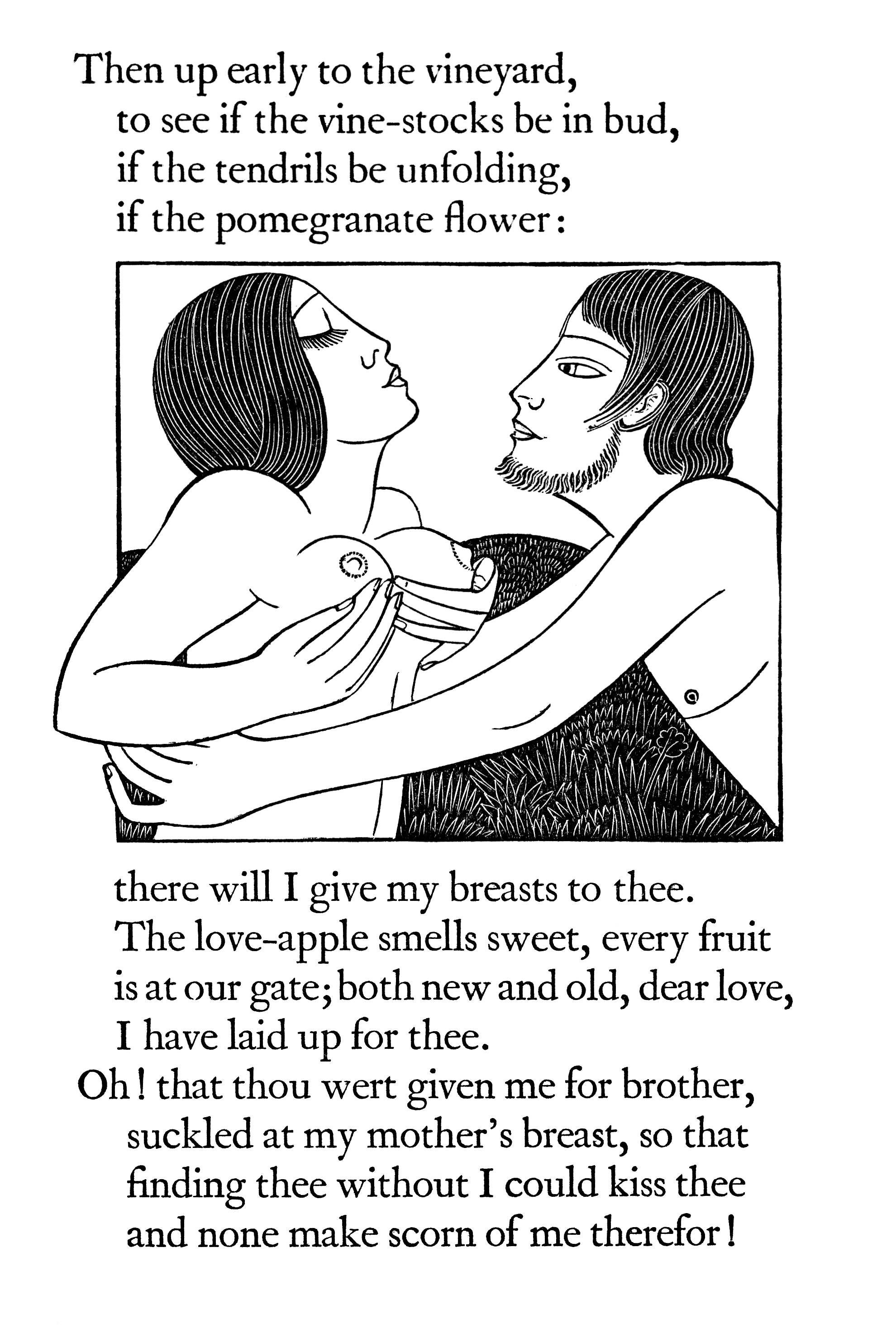

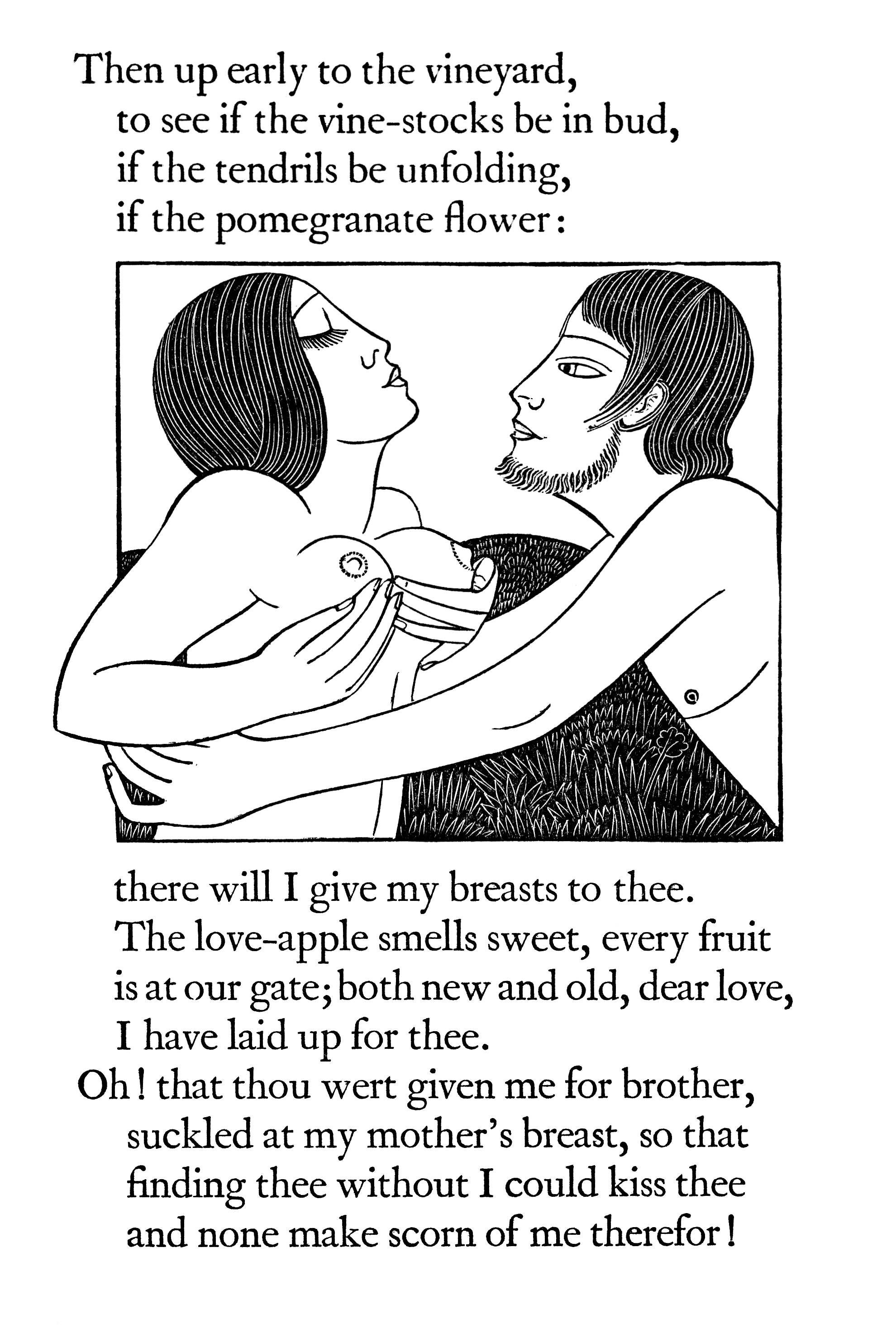

Figure 1

Page 39: “Ibi dabo tibi.” Eric Gill, The Song

of Songs” to redeem himself from the failure of the 1925 Golden

of Songs: Called by Many the Canticle of

Cockerel Press edition, but this perception is not supported by

Canticles. Waltham St. Lawrence, (Berkshire:

contemporary evidence.23 Reviews of the Golden Cockerel Press’s

Golden Cockerel Press, 1925.) Reproduced

The Song of Songs: Called by many the Canticle of Canticles expressed

from the original held by the Department of

admiration of Gill’s contributions to the volume. The Times Literary

Special Collections of the University Libraries

Supplement stated:

of Notre Dame.

And Mr. Eric Gill’s woodcuts, seventeen in all, perform the

21 Edward Johnston, [Canticum cantico-

triple function of being beautiful in themselves, of forming

rum], England, Wing MS ZW 945.J654,

a part, not an interruption, of the page, and of helping the

Newberry Library. Penciled on Johnston’s

reader’s imagination into the heart of this love-story.24

manuscript is “3 Hammersmith Terrace,”

which dates the manuscript to the time-

Subsequent assessments of the Golden Cockerel Press’s publication

frame between 1905 and 1912, when

Johnston resided at this address.

recognize it as a “definite advance in style” within Gill’s oeuvre.25

22 Eric Gill, Autobiography, 130.

Reviews contemporary to the publication of the Golden Cockerel’s

23 See Brinks, “In Search of Sensuality:

The Song of Songs demonstrate that Gill’s experiments with woodcut-

Kessler’s and Gill’s Song of Songs” (150)

ting and engraving techniques were also noted and valued. In an

for this argument.

article titled “On the appreciation of the modern woodcut,” Herbert

24 Harold Hannyngton Child, “Prints and

pictures,” Times Literary Supplement,

Furst cites Gill’s output as demonstrating the zenith of modern wood

November 26, 1925, 793.

engraving techniques:

25 R. A. Walker, “Engravings of Eric Gill,”

… to crown it all, Mr. Eric Gill uses the block of hard wood

The Print-Collector’s Quarterly, 15:2 (April

and engraves it in black-line as if it were a steel engraving—

1928), 162.

with the result that such cuts of his as “The Shepherdess”

26 Herbert Furst, “On the appreciation of

recently shown at the Redfern Gallery, look like, and are in

the modern woodcut,” Artwork, 2:6,

January to March 1926, 91. Reproduced

fact outline engravings—intaglio prints, but from wood

in the article is an unused print produced

instead of metal.26

for Golden Cockerel Press’s The Song

of Songs: “Swineherd,” 1925; see J. F.

Physick, The Engraved Work of Eric Gill

(London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office,

1963), catalog number 337.

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

7

These reviews and knowledge of Gill’s longstanding interest in the

text provide explanation as to why Gill would wish to illustrate the

“Song of Songs” twice in less than a decade and also offer insight

into factors that contributed to the design of the Cranach Press

publication. His previous work with the “Song of Songs“ allowed

Gill to enter into conversations with Kessler with firmly established

views about the content of the text and its interpretative potential.

The reviews demonstrate that Gill was being praised both for his

treatment of the text and for his willingness to experiment in tech-

nique and output—the latter of which would come to fruition in the

Cranach Press publication.

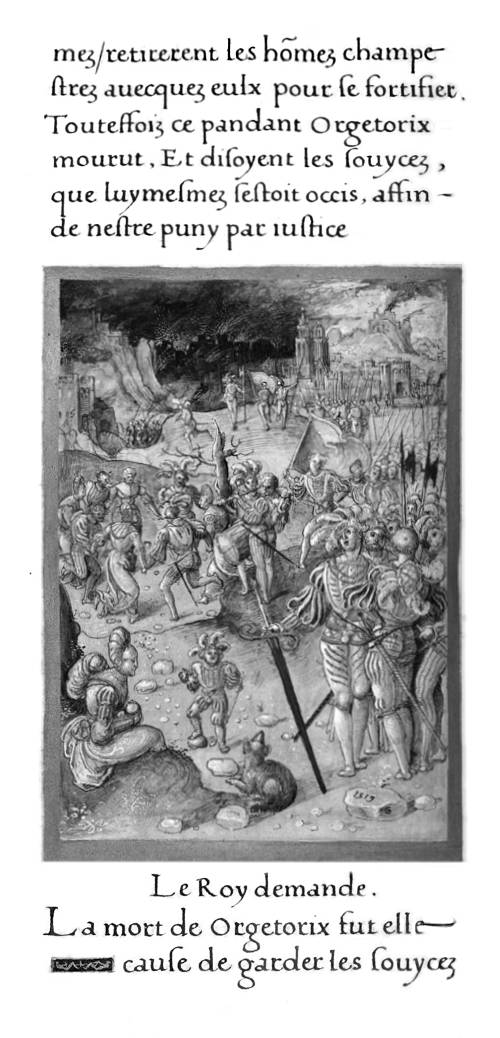

Kessler and Gill began focused discussions of the design

of the Cranach Press volume in September 1927. Both recorded in

their personal diaries a visit to the British Museum on September 21,

1927, during which they looked at several objects, including what

I believe can be identified as Les Commentaires de la guerre gallique,

Harley MS 6205, illuminated by Godefroy le Batave and dated to

1519.27 [see Figure 2] This manuscript is illuminated in semi-grisaille,

using a palette of grays and blues, with added highlights of gold.

Subsequent correspondence confirms that Kessler took note of both

the unusual dimensions (240 x 120mm) and the coloring of the

manuscript. He wrote to Gill on October 23, 1927:

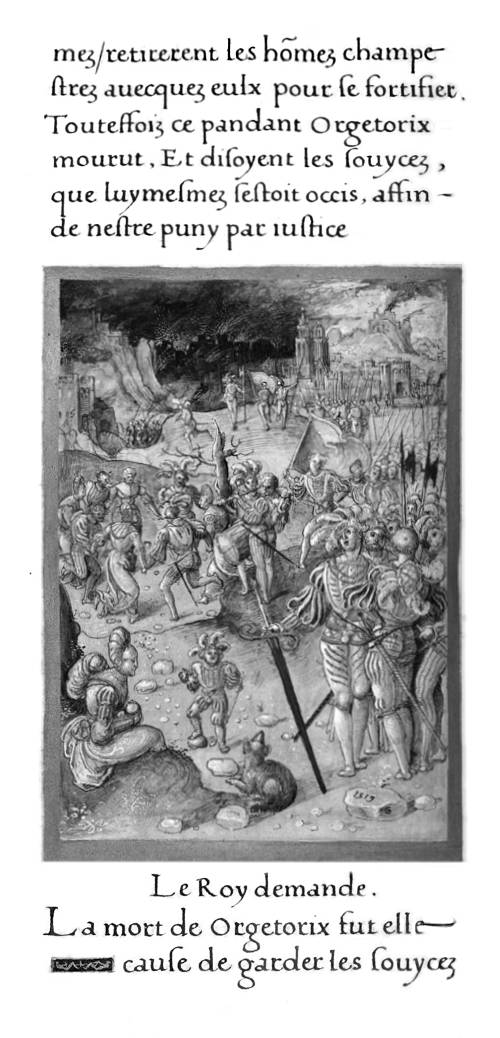

Figure 2

I also enclose proofs of the “Song of Songs.” There are

F. 9v: Swiss burning their villages. François

three different proofs. No 1. exactly the size of the British

du Moulin and Albert Pigghe, Commentaires

Museum manuscript, No. 2. one line longer and No. 3 two

de la guerre gallique, France, Central, 1519.

lines longer… If you could cut one illustration in three

London, British Library, Harley MS 6205,

blocks to be printed in black, grey and blue, I could have

saec. xvi1. Image © The British Library Board,

Harley MS 6205.

a number of different trial proofs printed and that would

give us something to start from.28

27 François du Moulin and Albert Pigghe,

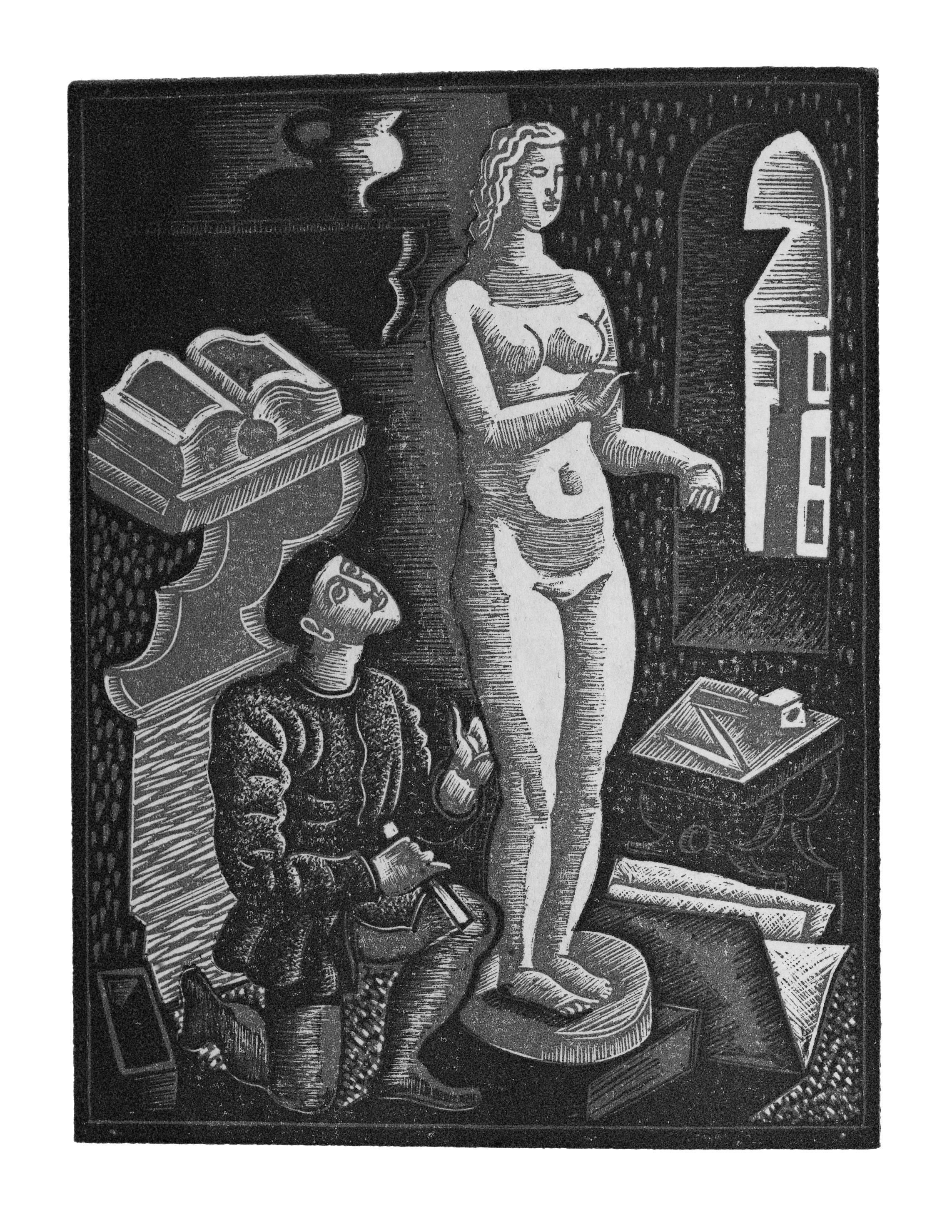

Despite these instructions, sketches record that Gill explored the use

Commentaires de la guerre gallique,

(France, Central, 1519). London, British

of a more liberal color palette as he began to work on initial designs

Library, Harley MS 6205, saec. xvi1;

for the project. An early sketch for “Nigra sum sed Formosa,”

details recorded in Kessler, Tagebuch,

preserved in an album labeled “orig. designs & first proofs of

Wednesday, September 21, 1927,

engravings,” reveals one of Gill’s first attempts at the visualization

Deutsches Literaturarchiv, Schiller-

of this pivotal text.29 [see Figure 3] While the sketch is undated, its

Nationalmuseum, as: “Ich gieng mit

beiden [Gill and Douglas Cockerell]

characteristically elongated format, which mimics the proportions

dann ins British Museum u. besah

of the Harley manuscript, strongly suggests that it was executed

mit Gill das schöne Manuscript eines

after their visit. It uses a subdued and judicious palette of pink and

Dialogs zwischen Caesar und Franz I von

green and includes several additional figures that are peripheral to

Frankreich, das für diesen von Albert

the central figural grouping, all of which would subsequently be

Pigghe geschrieben und mit Miniaturen

dropped by Gill. Another early sketch perhaps illustrates portions

geschmückt worden ist.”

28 Harry Graf Kessler to Eric Gill, October

of the “Song of Songs” included by Gill in his 1925 Golden Cockerel

23, 1927, Wing Modern M. S. Kess,

Press treatment of the text: “Come, love, let us fare forth into the

Newberry Library.

fields, and in the hamlet lodge. Then up early to the vineyard, to

29 Eric Gill, Canticum Canticorum Album,

see if the vine-stocks be in bud, if the tendrils be unfolding, if the

1930, 92.1.2799, Eric Gill Collection,

pomegranate flower: there I will give my breasts to thee.”30 It uses

Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas

at Austin.

the same color palette as the design for “Nigra sum sed Formosa,”

8

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

but integrates figures into a stylized landscape that would come to

be distinctive in all of the finished prints for the volume.31 Although

Gill did not develop either of these sketches for inclusion in the final

publication, his variation in approach and palette demonstrate that,

with the exception of the size parameters Kessler had provided, Gill

experimented profusely in his initial designs. Gill’s independent

thinking about the volume’s design would not ultimately result in

the use of color, but it did engender designs much more radical than

Kessler envisioned.

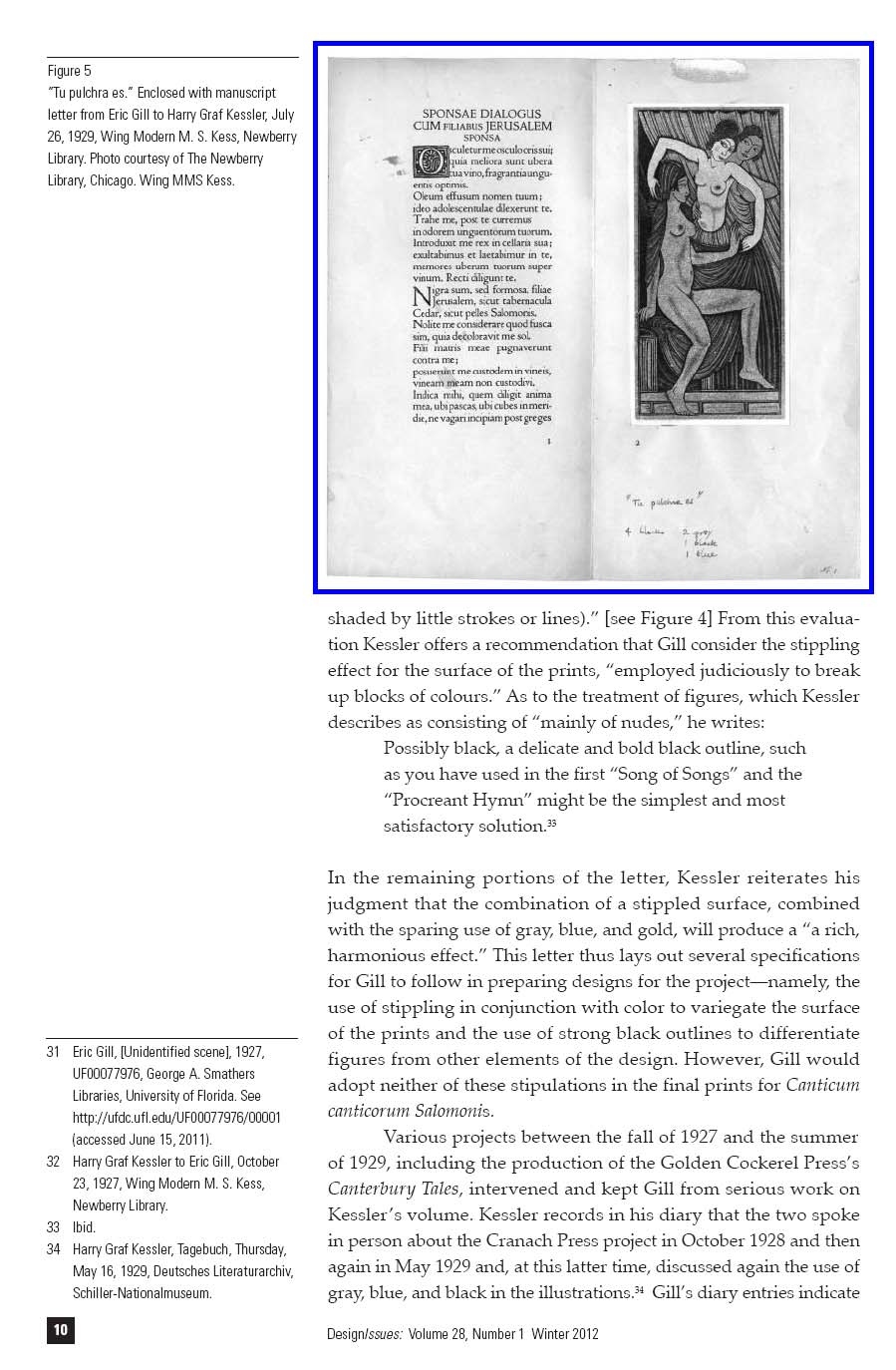

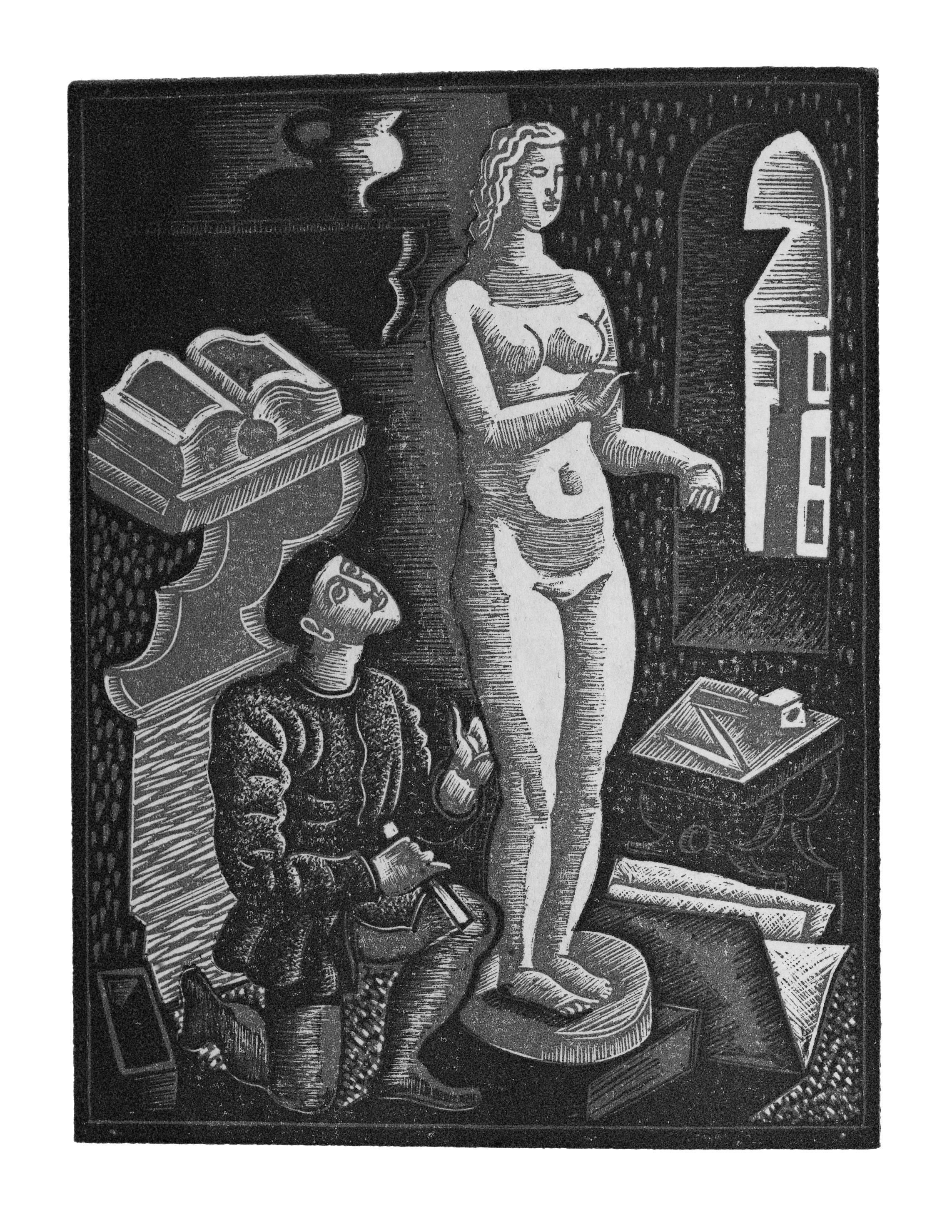

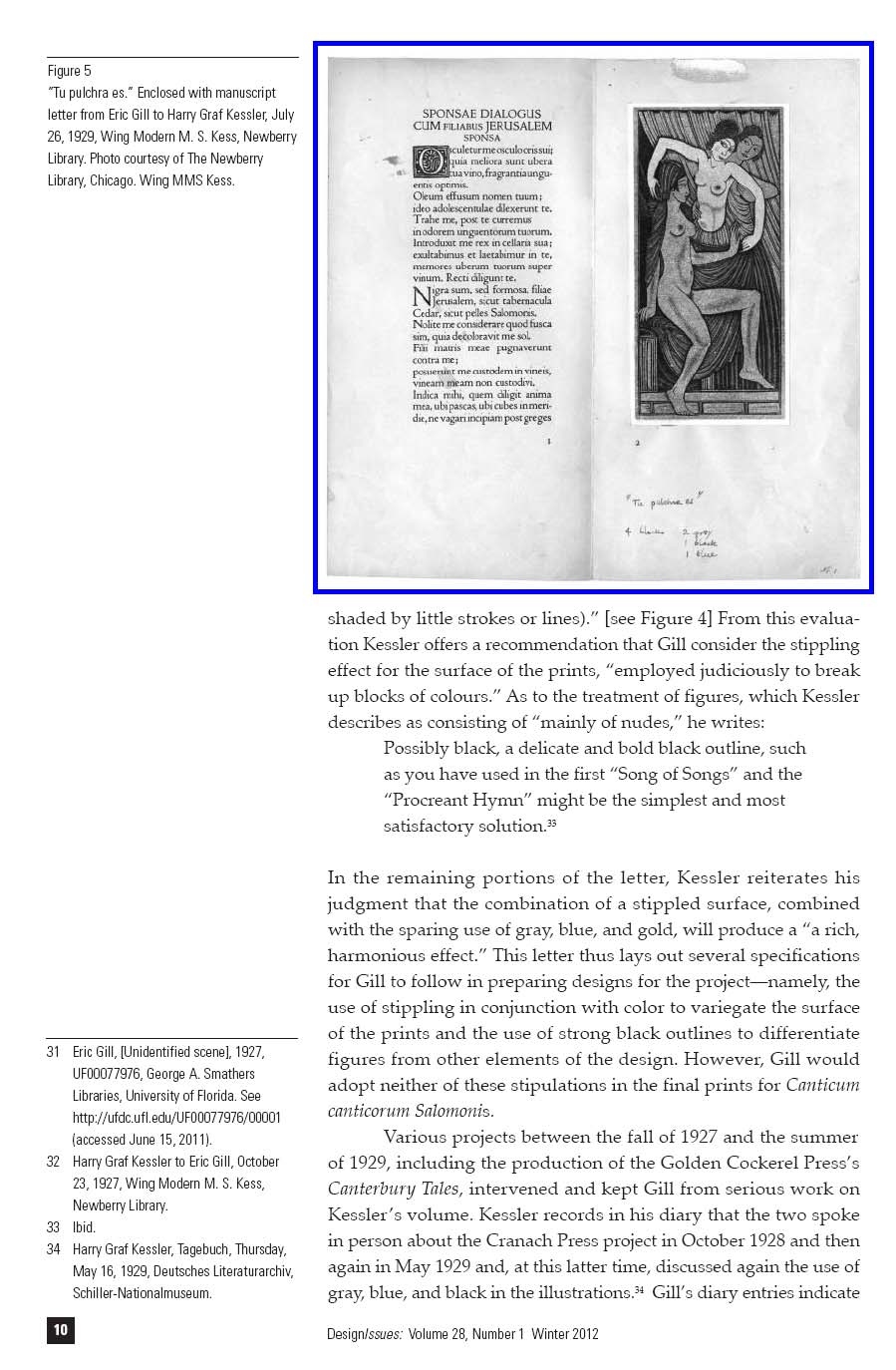

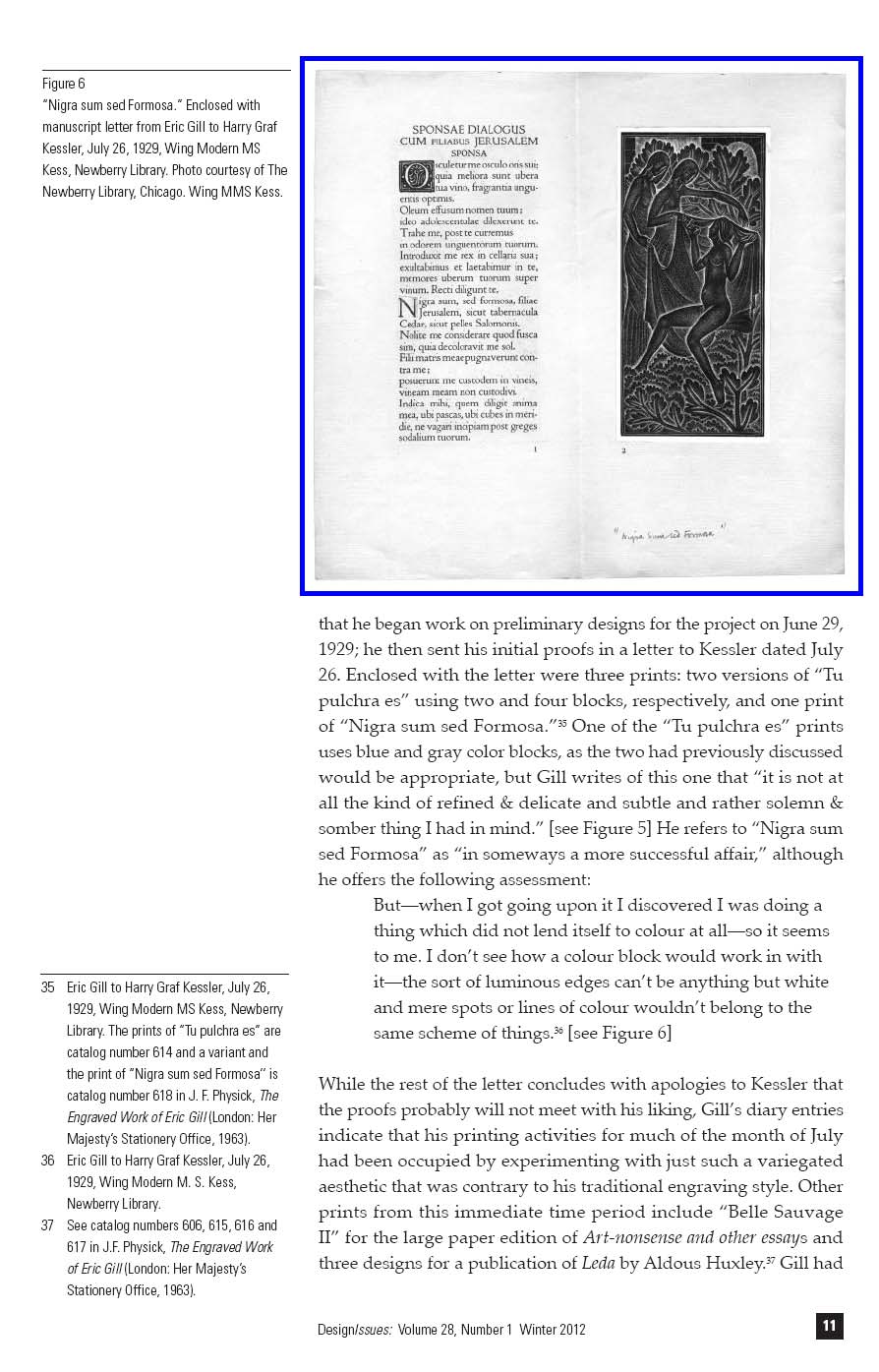

Kessler’s letter to Gill on October 23, 1927, also addressed the

potential technique of the prints to be used by Gill in the Cranach

Press publication. In the time between their visit to the British

Museum in September and the date of the letter, Gill had sent Kessler

a copy of Golden Cockerel Press’s The Metamorphosis of Pigmilions

Image, with engravings by Rene Ben Sussan—presumably as an

example of a contemporary volume using a muted color palette.

However, Kessler was not impressed with Ben Sussan’s technique

or use of color, describing the prints as “barbarous.”32 Kessler’s only

exception to this assessment was the doublet of Pigmalion found in

the frontispiece of the volume, which he describes as “stippled (not

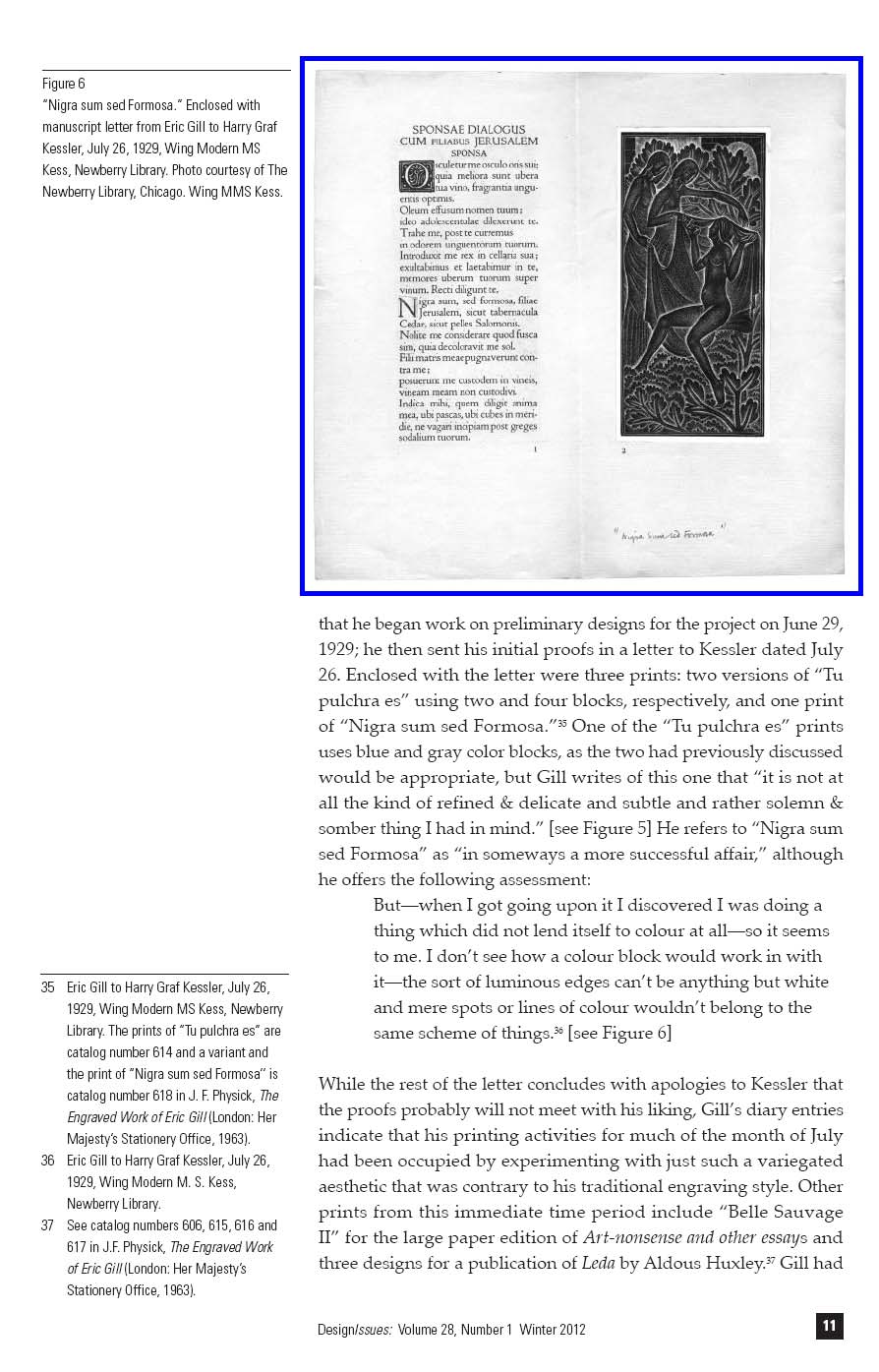

Figure 3 (above)

“Nigra sum sed Formosa.” Eric Gill, Canticum

Canticorum Album, 1930, 92.1.2799.

Eric Gill Collection, Harry Ransom Center,

The University of Texas at Austin. Photo

reproduced courtesy of the Harry Ransom

Center, The University of Texas at Austin.

Figure 4 (right)

Frontispiece. John Marston, illustrated by

Rene Ben Sussan, The Metamorphosis of

Pigmalions Image. Waltham St. Lawrence,

Berkshire: Golden Cockerel Press, 1926.

Reproduced from the original held by the

Department of Special Collections of the

University Libraries of Notre Dame.

30 A comparison of the Golden Cockerel

Press and Cranach Press editions shows

that eight of the same verses were

used in both editions, so Gill’s choosing

to experiment with a text that he had

treated in the past would not have been

unlikely; the verses used in common

are 1:12, 1:14, 2:8, 4:12, 5:2, 5:7, 7:12,

and 8:2 as numbered in the Douay-

Rhiems edition.

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

9

adopted Kessler’s suggestion to convey depth through stippling but

ultimately decided that such a technique and the use of color were

not compatible.

Although Kessler’s response to these initial prints has not

been located, Gill sent a letter to Kessler on August 2, 1929, that

states, “I was very glad to get your letter last evening … I am very

glad indeed that you like the prints I sent.”38 The two discussed

the project intermittently throughout the months of August and

September, and both recorded a meeting on September 25, 1929,

at Gill’s home at Pigotts near High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire.

At this meeting, they decided on a November delivery date for the

initial designs. Gill wrote to Kessler on October 26 that he was “now

about to begin designs for the S of Songs,” and his diary entries

indicate that he worked on the project throughout the early part of

November.39 Efforts stalled as both individuals worked on other proj-

ects during the following months, but they resumed efforts on this

project in March 1930. Gill worked throughout much of the spring

on prints and paste-ups; on June 4, he sent Kessler a note that read,

“I have now finished all the Engravings for the S. of S. except the

initials and am now starting on these. I enclose some rough proofs

which I hope you will like.”40 Gill and Kessler began making plans

for Gill to travel to Weimar for the printing of text proofs soon after.

Gill wrote on June 9:

38 Eric Gill to Harry Graf Kessler, August 2,

I am most glad that you are pleased with the Engravings, and

1929, Wing Modern M. S. Kess,

that Maillol also thinks well of them. I will bring the blocks

Newberry Library.

39 Eric Gill to Harry Graf Kessler,

when I come which will be towards the end of next week if

October 26, 1929, Wing Modern M. S.

that will be convenient to you.41

Kess, Newberry Library.

40 Eric Gill to Harry Graf Kessler, June 4,

Gill’s time in Weimar, while successful for the objectives

1930, Wing Modern M. S. Kess,

at hand, can also be read as a prelude to the difficult times ahead.

Newberry Library.

Gill records in his diary that he arrived at Weimar on June 30, 1930,

41 Eric Gill to Harry Graf Kessler, June 9,

1930, Wing Modern M. S. Kess,

with the sentiment, “Count Kessler met me at train station - most

Newberry Library.

kind.”42 Kessler describes the arrival somewhat differently: “Gill was

42 Eric Gill, Diary, June 30, 1930, M. S. Gill,

immediately visible in the station in his odd garb: knee stockings,

William Andrews Clark Memorial Library,

a short black cassock, and brightly colored scarf. He said that all of

University of California at Los Angeles.

Cologne was looking at his legs—was this perhaps because his stock-

43 Harry Graf Kessler, Tagebuch, Monday,

June 30, 1930, Deutsches Literaturarchiv,

ings were so thin? I think he likes the attention as an eccentric.”43

Schiller-Nationalmuseum.

Regardless, the two began work in the press almost immediately.

44 Eric Gill, Diary, June 30, 1930 to July 10,

Gill’s diary entries reveal that they spent the first few days of his

1930, M. S. Gill, William Andrews Clark

11-day visit engaged in printing trials at the press and the remaining

Memorial Library, University of California

time experimenting with gilding.44 Although the two had exchanged

at Los Angeles.

detailed letters and proofs by mail throughout the previous year, Gill

45 See the proof belonging to the St. Bride

Printing Library, London, reproduced in

had only recently begun the engraving of initial letters and other

Brinks, “In Search of Sensuality: Kessler’s

detail work. Early proofs of the first page of the Latin version of the

and Gill’s Song of Songs,” 155. The

text, for example, use initial letters that Gill had created in 1926 for

initial letters are catalog number 314 in

the Cranach Press’s The Eclogues of Virgil.45 Their time together in

J. F. Physick, The Engraved Work of Eric

Weimar thus represented their only chance to combine all of their

Gill (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery

Office, 1963).

individual contributions.

12

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

However, Kessler and Gill’s diverging aesthetic visions kept

them at odds about the finished product. Two issues in particular

concerning the production of the volume remained to be resolved

during Gill’s stay in Weimar: the use of colored inks for the running

title heads and initial letters and the gilding of engravings and

initials. Gill had written to Kessler that before his departure he

would go to London and procure colored inks to experiment with

while in Weimar.46 Their correspondence that took place immedi-

ately after Gill’s visit continued the discussions; on July 27, 1930,

Gill wrote: “I think Green (a bluish green) would look very well

with the blue & black but fear it might destroy the rather delicate

somberness we are aiming at.”47 Kessler continued his attempts

to integrate blue into the volume in the manner of the Harley Les

Commentaires de la guerre gallique manuscript, writing on December

30, 1930, of “… the letter C itself being printed in pure Lapislazuli

ultramarine. The effect I think magnificent.”48 Kessler also favored

the use of slender golden frames around the illustrations, in addition

to the other gilding.49 Kessler’s position both on the use of color and

on gilding imply that he wished for the finished volume to possess

an antiquated aesthetic, including rubricated and gilded initials set

off from the text frame. Gill, on the other hand, clearly had a more

46 Eric Gill to Harry Graf Kessler,

avant-garde effect in mind. His written comments always remained

June 9, 1930, Wing Modern M. S. Kess,

noncommittal about both color and gilding; for instance, he writes at

Newberry Library.

one point that, “[w]ith regard to the question of gilding, I will keep

47 Dated manuscript reply, in Gill’s hand,

this in mind and we wil make experiments when the engravings

written on Harry Graf Kessler to Eric Gill,

July 19, 1930, box 93, folder 9, M. S. Gill,

are done.”50 In the end, however, the changing state of finances both

William Andrews Clark Memorial Library,

for Kessler and for the Cranach Press did not allow either of these

University of California at Los Angeles.

luxuries to be carried out in production. Initial letters were gilded in

48 Harry Graf Kessler to Eric Gill, December

many of the deluxe copies, but no additional gilding or supplemental

30, 1930, box 93, folder 9, M. S. Gill,

ink colors, other than for the running titles, were used.

William Andrews Clark Memorial Library,

By the time the book was printed the following spring, the

University of California at Los Angeles.

49 Undated page from Kessler’s notebook,

distribution and sale of such luxury items was becoming increasingly

published in Brinks, “In Search of

difficult. Announcements were printed specifying that the Latin

Sensuality: Kessler’s and Gill’s Song of

edition would be sold in England at 3½ guineas each for copies on

Songs,” 153.

handmade paper, of which 200 were produced; at 7 guineas each

50 Eric Gill to Harry Graf Kessler, March 31,

for morocco-bound copies on Japanese paper, of which 60 were

1930, Wing Modern M. S. Kess,

Newberry Library.

produced; and at 30 guineas each for morocco-bound, hand-gilded

51 The Song of Songs in Latin publication

copies, of which 8 were produced.51 The prices for the first two cate-

announcement, box 26, folder 15,

gories were lowered almost immediately to 3 and 6 guineas, respec-

M. S. Gill, William Andrews Clark

tively; a letter to Gill from the Cranach Press, dated June 2, 1931,

Memorial Library, University of

clarified that, “[t]he price has for certain reasons appurtaining [sic] to

California at Los Angeles.

continental sale been reduced.”52 An agreement to handle sales was

52 Cranach Press to Eric Gill, June 2, 1931,

box 93, folder 9, M. S. Gill, William

struck with Douglas Cleverdon, who had worked extensively with

Andrews Clark Memorial Library,

Gill to publish and distribute The Engravings of Eric Gill. Although

University of California at Los Angeles.

disagreements surfaced as to the conditions of rebate that would

53 Harry Graf Kessler to Eric Gill, October

be offered to Cleverdon, his initial sales looked promising; he sold

5, 1931, box 93, folder 9, M. S. Gill,

three copies on vellum in advance of the month of October alone.53

William Andrews Clark Memorial Library,

University of California at Los Angeles.

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

13

As a result of both this encouraging start and the worsening financial

conditions in Germany, Kessler dispatched the whole Latin edition

to Gill on November 2. Their arrangement specified that Gill would

then provide copies to Cleverdon, upon Kessler’s direction, as they

were sold. Included in the agreement letter is Kessler’s assessment

of the volume and the situation as a whole:

I think it is one of the most beautiful series of illustrations

produced in modern times and that the book will appeal to

everybody and all interested in fine illustration and book

making. Of course, times are hard and difficult, but still one

must hope that a sufficient number of people and fortunes

have survived the crisis and will continue to buy fine books

and thus make their production possible.54

The books themselves were received by Gill at High Wycombe on

November 13, essentially removing Kessler from further control of

the sale.55 Thus, Kessler, who had at one time ef ectively dictated

every financial operation of the press, now depended on others for

the success of the publication.

The initially promising purchasing figures proved mislead-

ing, and sales of the book were dismal. Douglas Cleverdon halted

all communications with Kessler after November 1931 and sold

only a small number of the copies he had initially received. Sales

were so poor that Kessler was unable to pay Gill the sum of £55 for

work completed on the project. In a letter dated July 6, 1932, Kessler

explained that, “[i]t is practically impossible for me to send them

[£55] from Germany, and unfortunately, the way in which Cleverdon

has handled the “Song of Songs” business, has not made it possible

for me to pay you in England.”56 In addition, correspondence docu-

ments that Kessler tried to redeem the book’s reputation and sales

54 Harry Graf Kessler to Eric Gill,

over the next year by commissioning other booksellers to take over

November 2, 1931, box 93, folder 10,

M. S. Gill, William Andrews Clark

all transactions in England.57 However, the damage had already been

Memorial Library, University of California

done, and the publication did not receive the widespread acclaim

at Los Angeles.

and distribution that Kessler and Gil desired for it. Kessler contin-

55 Shipping receipt, dated November

ued to promote the volume, writing to Gill from exile in Palma de

13, 1931, box 93, folder 10, M. S. Gill,

Mallorca in May 1935 that Gill should send “a few copies of this

William Andrews Clark Memorial Library,

University of California at Los Angeles.

most beautiful book” to be displayed in an exhibition there.58 The

56 Harry Graf Kessler to Eric Gill, July

letter makes clear that, while Kessler was forced to occupy himself

6, 1932, box 93, folder 10, M. S. Gill,

in Spain in reminiscence, mounting an exhibition of Cranach Press

William Andrews Clark Memorial Library,

books and working on his memoirs, Gill had moved on to other

University of California at Los Angeles.

work and new commissions. Kessler begins the letter:

57 Harry Graf Kessler to Eric Gill, September

I have not heard from you for so long, that I am beginning

20, 1932, box 93, folder 10, M. S. Gill,

William Andrews Clark Memorial Library,

to feel rather anxious, lest you should have entirely forgotten

University of California at Los Angeles.

me. I think of you often, and am glad sometimes to hear about

58 Harry Graf Kessler to Eric Gill, May

you through the papers.59

6, 1935, box 93, folder 10, M. S. Gill,

William Andrews Clark Memorial Library,

University of California at Los Angeles.

59 Ibid.

14

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

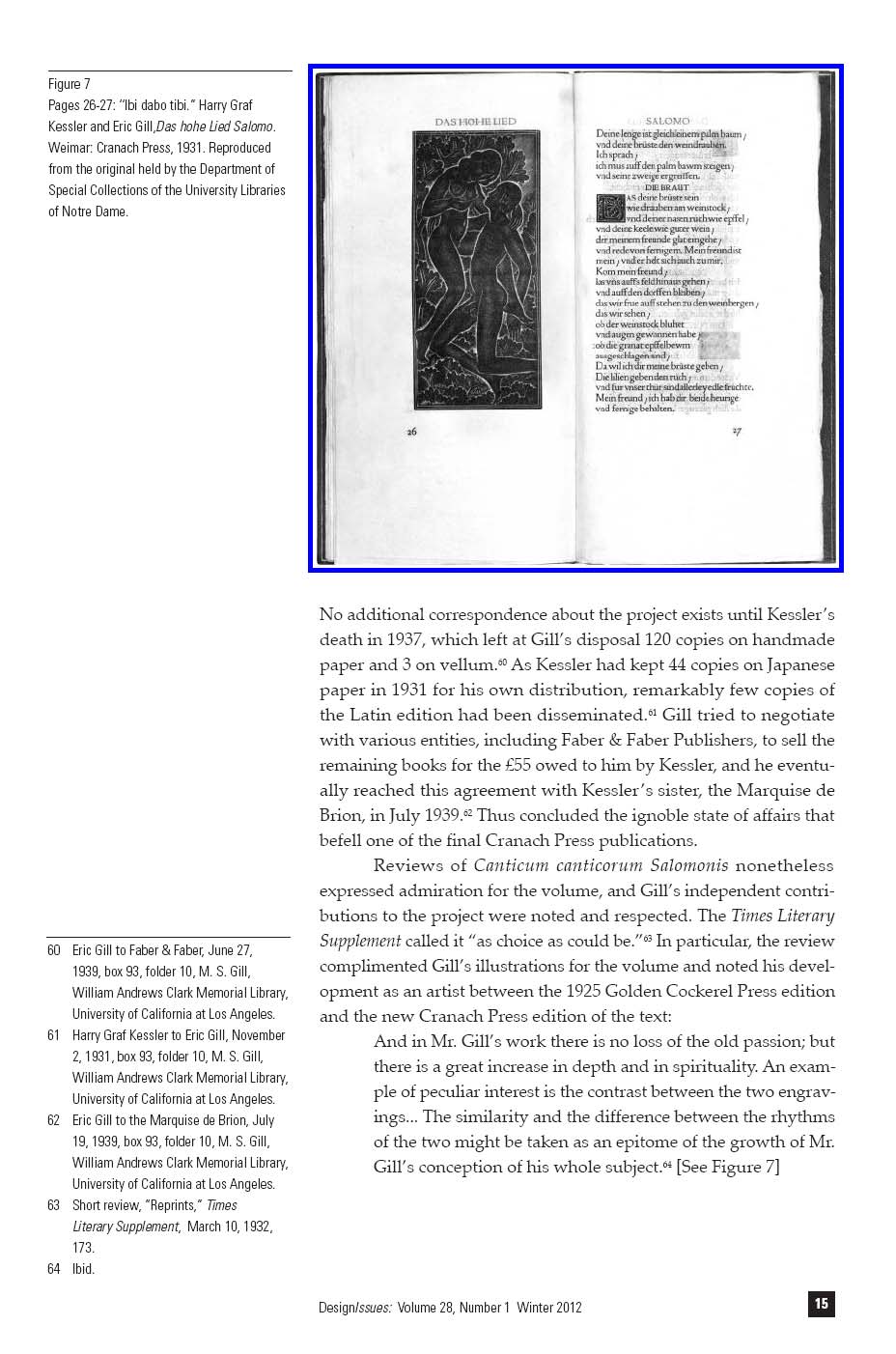

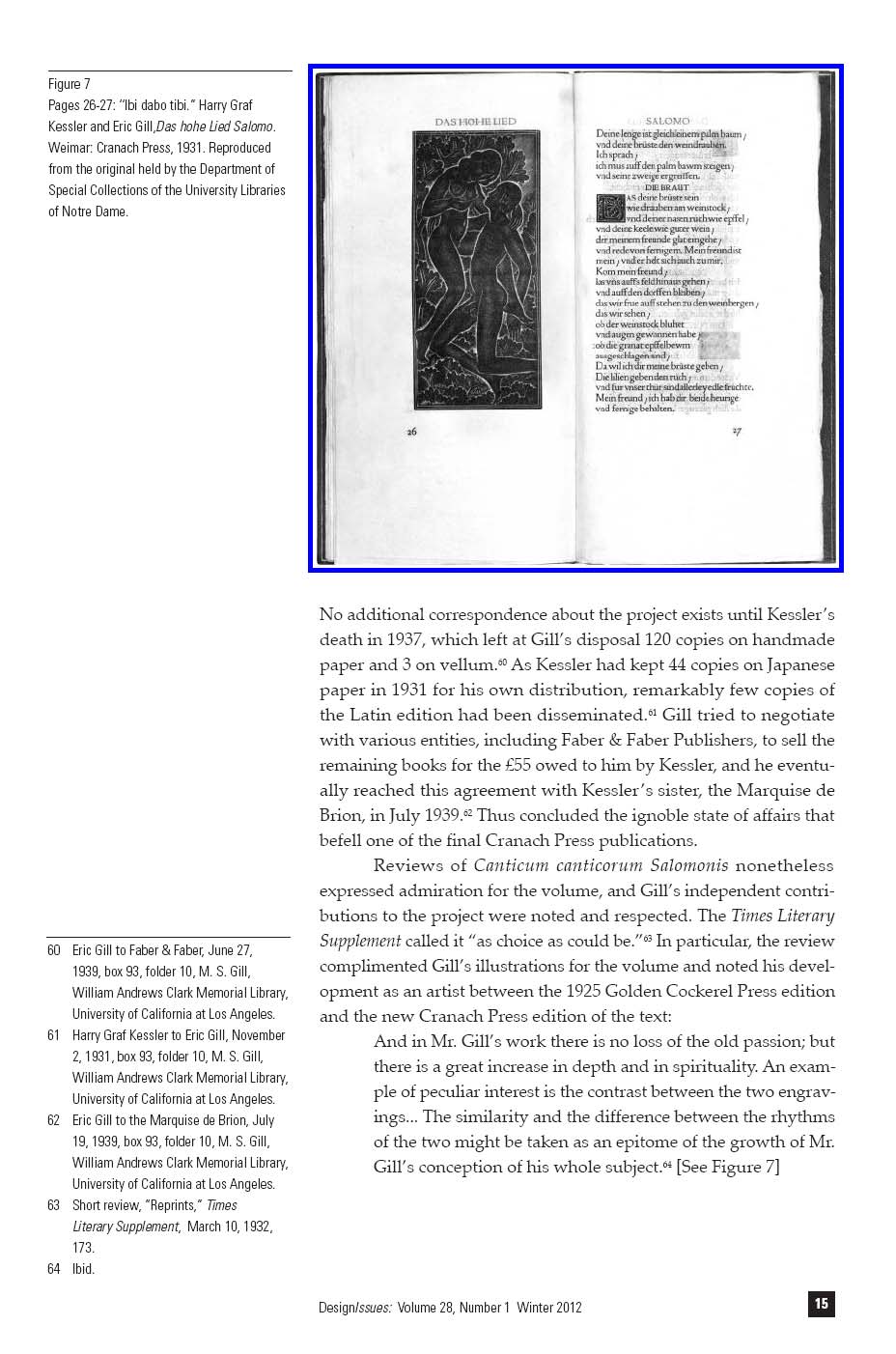

Gill’s own bookkeeping records indicate that individual prints

sold well; in fact, all prints except for “Invenerunt me custodes” and

“Dilecti mei pulsantis” sold out.65 Reviews outside of England also

praised Gill’s efforts. Rudolph Alexander Schröder, who previewed

the volume before it was available for general sale, wrote:

Gill will present himself as an illustrator and illuminator who

here, in his very first attempt, reaches an inventiveness and

technical mastery that is absolutely incomparable. His prints

will combine the hieratic splendor of the most opulent works

by Morris with a totally new sensuous life and with a unique

style that, in my opinion, raise this unfinished book into an

example of the spiritual essence and the conceptual free-

dom that make the products of the Cranach Press, which

in so many ways seem directed against the taste and tendency

of their times, in truth works that speak to the highest needs

of their age.66

More modern assessments of the volume also express admira-

tion but frequently overlook Canticum canticorum Salomonis in favor

of Gill’s Four Gospels among his illustration cycles.67 The former’s

prints are often described as “luminous” or “sensuous,” but little of

depth has been written about the shift in style in their technique and

their avant-garde appearance in relation to Gill’s earlier prints. This

essay aims to promote Gill’s innovations and contextualize them

within the final product of Canticum canticorum Salomonis. The tech-

nique and content of the illustrations, which in the past have been

tied to Kessler’s oversight, instead rest firmly with Gill, as do the

selection of the text and the volume’s production details. Although

Kessler held the upper hand throughout much of their long, collab-

orative working relationship, Gill’s emotional connection to the text

of the “Song of Songs” and his confidence in his technique and artis-

tic vision for the text provided him with the maturity and authority

to guide the production of Canticum canticorum Salomonis.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank David T. Gura, John F. Sherman, Dennis

65 Eric Gill, List of work, 1910-1940, series

7.1, M. S. Gill, William Andrews Clark

Doordan, and Tobias Boes for insightful comments on early drafts

Memorial Library, University of California

of this article. Special gratitude is owed to Ruth Cribb, whose disser-

at Los Angeles. These are catalog

tation research on Eric Gill’s daily working habits facilitated the

numbers 665 and 668 in J. F. Physick, The

archival research of this project immeasurably.

Engraved Work of Eric Gill (London: Her

Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1963).

66 Rudolph Alexander Schröder, “Die

Cranach-Presse in Weimar,”

Imprimatur: Ein Jahrbuch für

Bücherfreunde, 1931, 103.

67 See, for example, John Harthan, The

History of the Illustrated Book: the

Western tradition (London: Thames

and Hudson), 269.

16

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

Bibliography

Brinks, John Dieter, “In Search of Sensuality: Kessler’s and Gill’s Song of Songs,” The Book as

a Work of Art: The Cranach Press of Count Harry Kessler. Ed. John Dieter Brinks. (Laubach:

Triton, 2005). 146-169.

Child, Harold Hannyngton, “Prints and pictures,” Times Literary Supplement, November 26, 1925:

793.

Gill, Eric, Autobiography, (New York: Devin-Adair, 1941).

Gill, Eric, Art-nonsense and Other Essays, (London: Cassell & Co., Ltd., 1929).

Gill, Eric, Canticum Canticorum Album, 1930, Eric Gill Collection, Harry Ransom Center, University

of Texas at Austin.

Gill, Eric, Engravings by Eric Gill: a selection of engravings on wood and metal representative of

his work to the end of the year 1927: with a complete chronological list of engravings and a

preface by the artist, (Bristol: D. Cleverdon, 1929).

Gill, Eric, “The Song of Solomon and such-like songs,” The Game, (Ditchling: D. Pepler, 1921).

Gill, Eric, Eric Gill Archive, 1887-2003, M. S. Gill, William Andrews Clark Memorial Library,

University of California at Los Angeles.

Gill, Eric, Eric Gill Collection, George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida.

Gill, Eric, The Song of Songs: Called by many the Canticle of canticles. (Waltham St. Lawrence:

Golden Cockerel Press, 1925).

Gill, Eric, Songs Without Clothes: being a dissertation on the Song of Solomon and such-like

songs, (Ditchling: St. Dominic’s Press, 1921).

Easton, Laird M. The Red Count: the life and times of Harry Kessler, (Berkeley: The University of

California Press, 2002).

Harthan, John, The History of the Illustrated Book: the Western tradition, (London: Thames and

Hudson, 1981).

Johnston, Edward, [Canticum canticorum], Wing MS ZW 945 .J654, Newberry Library.

Kessler, Harry Graf and Eric Gill, Canticum canticorum Salomonis quod Hebraice dicitur Sir

hasirim. (Weimar: Cranach Press, 1931).

Kessler, Harry Graf, Count Harry Kessler papers 1898-1937, Wing Modern MS Kess,

Newberry Library.

Kessler, Harry Graf, Das Tagebuch 1880-1937, (Stuttgart: Cotta, 2004).

Marston, John, with illustrations by Rene Ben Sussan, The Metamorphosis of Pigmalions Image,

(Waltham St. Lawrence, Berkshire: Golden Cockerel Press, 1926).

Moulin, François du and Albert Pigghe, Commentaires de la guerre gallique, London, British

Library, Harley MS 6205, saec. xvi1.

Müller-Krumbach, Renate, Harry Graf Kessler und die Cranach-Press in Weimar, (Hamburg:

Maximilian-Gesellschaft, 1969).

Physick, J. F. The Engraved Work of Eric Gill. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1963.

“Reprints.” Times Literary Supplement, March 10, 1932: 173.

Schröder, Rudolph Alexander. “Die Cranach-Presse in Weimar.” Imprimatur: Ein Jahrbuch für

Bücherfreunde, (1931): 91-112.

Walker, R. A., “Engravings of Eric Gill,” The Print-Collector’s Quarterly, 15.2 (1928): 162.

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

17