Social Theory as a Thinking Tool

for Empathic Design

Carolien Postma, Kristina Lauche,

Figure 1a

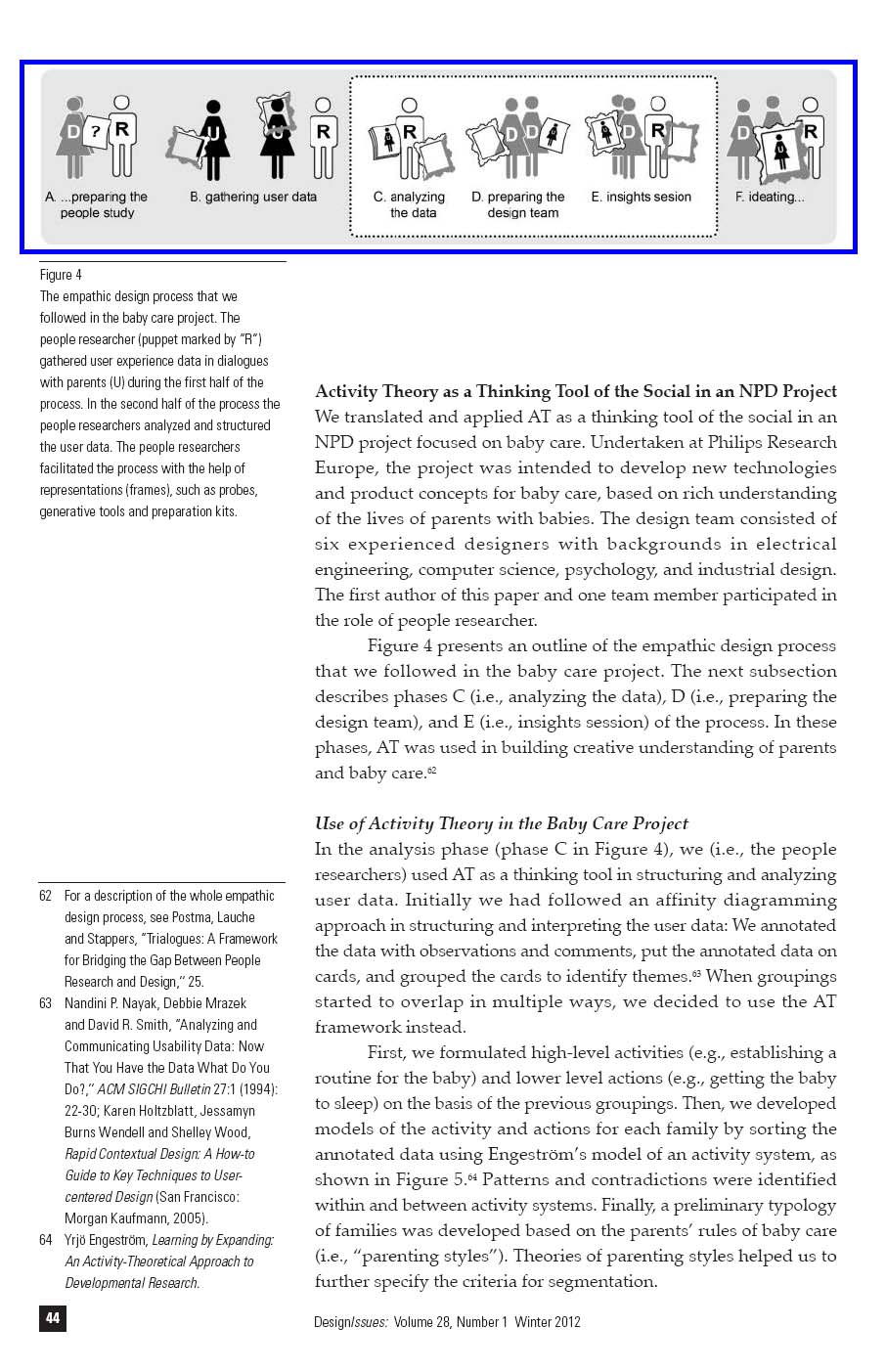

Pieter Jan Stappers

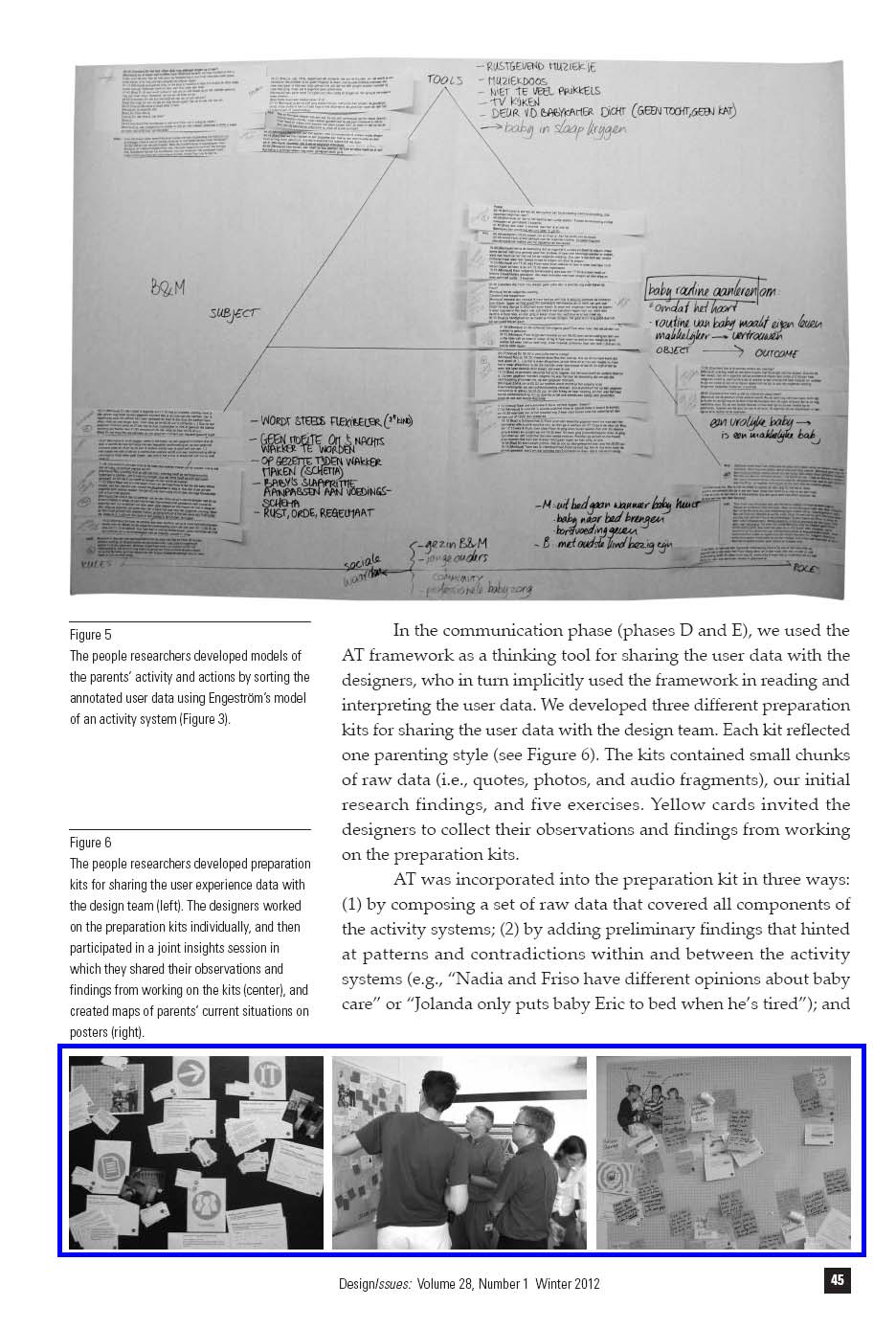

Showing a personal SMS message to a friend

is a way of communicating trust and friend-

ship. See Alex S. Taylor and Richard Harper,

“The Gift of the Gab?: A Design-oriented

Sociology of Young People’s Use of Mobiles,”

Computer Supported Cooperative Work 12:3,

(2003): 267-96.

Introduction

Figure 1b

Recent societal issues and socio-technological developments,

When faced with buying wine in the super-

including the mass adoption of real-time social media services,1 have

market, we often choose the bottle of wine

made “the social” (i.e., the relationality inherent in human existence)

from a nearly empty shelf, assuming it’s the

an essential topic for design. Despite the fundamentally social nature

best one. See Thomas Erickson and Wendy A.

Kellogg, “Social Translucence: An Approach

of life, most existing models intended to generate perspectives of

to Designing Systems that Support Social

users in design still focus on the individual. To support designers

Processes,” ACM Transactions on Computer-

in doing empathic design, we set out to find a possible conceptual

Human Interaction 7:1 (2000): 59-83.

framework that could serve as a “thinking tool” of the social. A

model that sensitizes designers toward both relationality and

Figure 1c

individuality in building creative understanding of users for

In a people study about baby care (see

section 5), dads with new-born children

design. In this paper, we review a number of possible frameworks

who were breast-fed, said they felt that

and describe our experiences in applying these frameworks in new

their bond with the child was rather remote,

product development (NPD) practice.

because they didn’t have any role in the

a

b

breast feeding. In case of bottle-feeding,

moms and dads would often feed the child in

turns, or even together.

Figure 1d

Sometimes my dad gives me a ride to the bus

station. When we are in a hurry, I jump into

the back seat of the car. My dad doesn’t like

that: He says it makes him feel as if he’s a

c

d

taxi driver.

Figure 1e

The table arrangement in a restaurant influ-

ences how guests will interact during dinner

and with whom. See William W. Gaver,

“Affordances for Interaction: The Social is

Material for Design,” Ecological Psychology

8:2 (1996): 111-29.

e

f

Figure 1f

In a previous people study, a senior couple

explained that every week, their friends would

put six eggs up for raffle during their dancing

classes. It was an exciting event, and all the

people would bring their empty egg boxes,

just in case...

© 2011 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

30

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

In this paper we use “the social” to denote the idea that

1 Contagious, “Most Contagious 2009,”

human activity is fundamental y social, as opposed to individual.

Contagious, www.contagiousmagazine.

Figure 1 presents six cases from daily life. A closer look at these

com (accessed December 19, 2009).

cases reveals that the social plays an important role in each of these

2 David Benyon, Phil Turner and

six cases, and that the social is more than just another flavor of

Susan Turner, “Designing Interactive

Systems: People, Activities, Contexts,

context: The social permeates our lives. This idea has been at the

Technologies” (Harlow: Pearson

core of computer-supported cooperative work but is only peripheral

Education Ltd, 2005).

in design and design research.2 The suggestion has been made in

3 Examples are: Richard Buchanan, “Design

the design research literature that design teams need to establish

Research and the New Learning,” Design

creative understanding of the social to develop products and

Issues 17:4 (Autumn, 1999): 3-23; Alison

Black, “Empathic Design, User Focused

services that delight users.3 However, most frameworks of user

Strategies for Innovation,” Proceedings

experience in design place the individual at the center and merely

of New Product Development, IBC

hint at the social, leaving design teams rather empty-handed,

Conferences, (1998): 1-8; and Jane Fulton

or at least ill-informed. Therefore, a theoretical framework is

Suri and Matthew Marsh, “Scenario

needed to sensitize designers toward the social in designing for

Building as an Ergonomics Method in

Consumer Product Design,”Applied

user experience.4

Ergonomics 31 (2000): 151-7.

Our work is situated in the context of empathic design in NPD

4 Katja Battarbee and Ilpo Koskinen,

practice.5 Empathic design approaches often suggest that members

“Co-experience: Product Experience as

of a design team (who may or may not be educated in design) adopt

Social Interaction,” Product Experience,

the role of people researchers and directly interact with users to

ed. Hendrik N. J. Schifferstein and

ensure that the user perspective is included in design. However,

Paul Hekkert (San Diego: Elsevier Ltd,

2008), 461.

in NPD practice, this interaction is not always feasible because

5 Jane Fulton Suri, “Empathic Design:

people research is often outsourced or conducted by experienced

Informed and Inspired by Other People’s

people researchers. Alternatively, design teams might be engaged

Experience,” Empathic Design, User

in analyzing and structuring the user experience data that have

Experience in Product Design, ed. Ilpo

been gathered in people research.6 Such an approach means that

Koskinen, Katja Battarbee and Tuuli

Mattelmäki (Edita: IT Press, 2003), 51;

designers need conceptual tools that enable them to think about

Ilpo Koskinen and Katja Battarbee,

the social without having to become social scientists themselves. To

“Introduction to User Experience and

guide multi-disciplinary design teams in making sense of user data

Empathic Design,” Empathic Design,

for design, we searched for a thinking tool of the social. We dove into

User Experience in Product Design, ed.

social theory, aiming not to develop a new model of the social, but

Ilpo Koskinen, Katja Battarbee and Tuuli

Mattelmäki (Edita: IT Press, 2003), 37;

to find a theoretical framework that design teams in practice could

and Elizabeth B.-N. Sanders and Uday

use as a thinking tool of the social in analyzing and structuring user

Dandavate, “Design for Experiencing:

experience data.

New Tools,” Proceedings of the First

The paper proceeds in three parts. First, we explain the

International Conference on Design

context of our search and identify search criteria. Second, we review

and Emotion (Delft: Delft University of

five types of existing frameworks: special effect theories, relational

Technology, 1999): 87-91.

6 Carolien E. Postma, Kristina Lauche

frameworks, catalogues, metaphors, and scaffolds of context. In the

and Pieter Jan Stappers, “Trialogues:

third part, we focus on activity theory as having the best fit with

A Framework for Bridging the Gap

design teams’ needs, and show how we used it within an empathic

Between People Research and Design,”

design project in industry.

Proceedings of Designing Pleasurable

Products and Interfaces (2009): 25-34.

7 Fulton Suri, “Empathic Design:

Criteria for Assessing Frameworks for Empathic Design in Practice

Informed and Inspired by Other People’s

Empathic design is a relatively new branch of user-centered

Experience,” 51; Koskinen and Battarbee,

design approaches that support design teams in building creative

“Introduction to User Experience and

understanding of users and their everyday lives for NPD.7 The

Empathic Design,” 37; Sanders and

approach is considered most valuable in the fuzzy front end of

Dandavate, “Design for experiencing:

New Tools,” 87-91.

NPD, when product opportunities need to be identified and product

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

31

concepts developed.8 Empathic design uses a variety of methods

8 Koskinen and Battarbee, “Introduction

and techniques, including design probes,9 generative techniques,10

to User Experience and Empathic

context-mapping,11 and experience prototyping.12 These methods

Design,” 37.

9 Tuuli Mattelmäki, Design Probes,

and techniques are typically design-led (as opposed to research-

Doctoral Thesis (Helsinki: University

led) in that they focus on understanding and transforming users’

of Art and Design Helsinki, 2006).

experiences.13 The idea is not to find the ultimate truth about people

10 Elizabeth B.-N. Sanders, “Generative

and their environment, but to build an understanding that enables

tools for codesigning,” in Collaborative

designers to propose possible new futures.14

Design, ed. Stephen A. R. Scrivener,

Based on a literature review, Postma, Zwartkruis-Pelgrim,

Linden J. Ball and Andree Woodstock

(London): Springer-Verlag, 2000), 3.

Daemen, and Du identified four principles of empathic design:

11 Froukje Sleeswijk Visser and others,

1. Addressing people’s rationality and their emotions in

“Contextmapping: Experiences from

product use in a balanced way by combining observations

Practice,” CoDesign 1:2 (2005): 119-49.

of people’s actions with interpretations of their thoughts,

12 Marion Buchenau and Jane Fulton Suri,

feelings, and dreams.

“Experience Prototyping,” in Proceedings

of Designing Interactive Systems (New

2. Making empathic inferences about prospective users, their

York: ACM Press, 2000): 424-33.

thoughts, feelings, and dreams, and their possible futures of

13 Katja Battarbee, Co-experience, Doctoral

product use.

Thesis (Helsinki: University of Art

3. Involving users as partners in NPD, so that researchers

and Design, 2004); Marc Steen, The

and designers can continually develop and check their

Fragility of Human-Centered Design,

creative understanding in dialogue with users.

Doctoral Thesis (Delft: Delft University of

Technology, 2008).

4. Engaging the design team members as multi-disciplinary

14 Esko Kurvinen, Prototyping Social Action,

experts in people research, thus encouraging researchers

Doctoral Thesis (Helsinki: University of

and designers to join forces in designing and conducting

Art and Design Helsinki, 2007).

people research to ensure that the users’ perspectives are

15 Carolien E. Postma and others, “Doing

included in NPD.15

Empathic Design: Experiences from

Industry” (under review, 2011).

16 Jane Fulton Suri, “The Experience

The first two principals have implications for the qualities of the

Evolution: Developments in Design

intended thinking tool of the social. The third and fourth principles

Practice,” The Design Journal 6:2

determine the context in which the thinking tool of the social will

(2003): 39-48; Peter Wright and John

be used. In NPD practice, direct interaction between users and all

McCarthy, “Empathy and Experience in

members of a design team is often not feasible. People research is

HCI,” in Proceedings of Human Factors

in Computing Systems (New York:

often either outsourced or conducted by experts who may not be

ACM Press, 2008): 637-46; Froukje

part of the design team; or it happens long before a design team is

Sleeswijk Visser, Remko Van der Lugt

formed. As a result of these approaches, the user experience data

and Pieter Jan Stappers, “Sharing User

need to be conveyed to the design team. The “rich” and “personal”—

Experiences in the Product Innovation

qualities of user data that are required for building creative

Process: Participatory Design Needs

Participatory Communication,” Creativity

understanding—are often lost in this process.16

and Innovation Management 16:1 (2007):

A possible solution to sharing rich user data in design research

35-45.

practice is to engage the design team in analyzing and structuring

17 Postma, Lauche and Stappers,

the data after they have been pre-structured and pre-analyzed by the

“Trialogues: A Framework for Bbridging

people researchers. By reading, interpreting, and explaining users’

the Gap Between People Research and

stories, team members make the data their own and build creative

Design,” 25-34.

18 Hugh Beyer and Karen Holtzblatt,

understanding of users’ experiences.17 To facilitate this process for

Contextual Design: Defining Customer-

designers, we searched for a conceptual framework as a thinking

centered Systems. (San Francisco):

tool of the social.

Morgan Kaufmann, 1998).

Five criteria formed the starting point of our search. The

19 Veesa Jääskö and Tuuli Mattelmäki,

first criterion was informed by empathic design’s objective that

“Observing and Probing,” in Proceedings

of Designing Pleasurable Products

understanding users’ experiences should drive the development of

32

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

people-centered products and services. Sensitizing design teams to

the social is not enough, however; designers also need to obtain a

Footnote 19 continued

sense of how their designs relate to the social in envisioning possible

and Interfaces (2003), 126-31; Froukje

futures of product use and in developing products and services that

Sleeswijk Visser, Bringing the everyday

life of people into design, Doctoral

fit into people’s social lives. Therefore, the framework needs to

Thesis (Delft: Delft University of

address the social in relation to the materiality of product use.

Technology, 2009).

The second criterion was informed by the constraints of

20 Benjamin B. Bederson and Ben

empathic design in NPD practice, in which not every design team

Shneiderman, The Craft of Information

Visualization: Readings and Reflections

member is experienced in people research. Because we potentially

(San Francisco): Morgan Kaufmann, 2003);

want to engage all team members in analyzing and structuring

Ben Shneiderman, “Foreword,” in Human-

user data, the framework should provide experienced people

computer Interaction and Management

researchers with (new) perspectives of the social, while also offering

Information Systems: Foundations.

designers “handles” for the social. Such “handles” include Beyer &

Advances in Management Innovation

Systems, Volume 5, ed. Ping Zhang, Ben

Holtzblatt’s work models in the contextual design approach.18 They

Shneiderman and Dennis F. Galletta

provide a limited set of concrete themes or perspectives along which

(Armonk): M. E. Sharpe, Inc., 2006), ix.

findings from people research can be organized. However, their

21 Postma, Lauche and Stappers, “Trialogues:

models fall short as a thinking tool of the social in empathic design

A Framework for Bridging the Gap

because contextual design mainly focuses on examining the rational

Between People Research and Design,”

25-34; Sleeswijk Visser, Bringing the

domain.19 Moreover, contextual design does not offer a theoretical

Everyday Life of People Into Design.

framework that designers (and researchers) may use as a thinking

22 Michael A. Hogg and Graham M.

tool in interpreting and explaining social practices.

Vaughan, Social Psychology, fourth

Three further criteria were taken from Bederson and

edition (London: Pearson Prentice

Shneiderman’s classification of theories and frameworks.20 They

Hall: 2005).

23 Ibid.

identify five categories: (1) descriptive frameworks that identify key

24 Hall (1966) introduced the term

concepts; (2) explanatory frameworks that explain relationships and

“proxemics” to refer to the study of

processes; (3) predictive frameworks that help predict performance

how people unconsciously structure their

of people, organizations, or economies; (4) prescriptive frameworks

immediate surroundings. One type of

that provide guidelines based on best practice; and (5) generative

spatial organization is “informal space,”

or “interpersonal distance.” Interpersonal

frameworks that support generating new ideas by providing ways of

distance is one way people use to

seeing what is missing and what needs to be done. The thinking tool

establish and maintain a desired level of

we propose requires a framework that is descriptive of the social and

involvement in social interaction, e.g., in

material, explanatory of relationships and processes, and generative

greeting, caressing or conversing. Hall

in terms of facilitating the identification of patterns and trends in

distinguished four distance zones, ranging

from very close to the individual to further

user data and of opportunities for NPD. The framework also might

away: An intimate zone, a personal zone,

be prescriptive in that it suggests ways of studying user experience

a social zone, and a public zone. Which

data; however, these ways should not interfere with designers’

zone people adopt depends on the context

established practices and cultures to such a degree that they keep

of the social encounter; the setting, social

designers from using the framework.21

relationship and environmental conditions.

In some situations, people are not able

to adopt their preferred social distance,

Examination of Possible Frameworks

for example, in an elevator or crowded

On the basis of the criteria identified, we examined frameworks in

train, which may lead to discomfort.

the literature and tried out candidate frameworks in NPD projects

See John R. Aiello, “Human Spatial

in industry. We began our search in social psychology and environ-

Behavior,” in Handbook of Environmental

Psychology, ed. Daniel Stokols and

mental psychology literature and then expanded the search to

Irwin Altman (New York: John Wiley &

the human-computer interaction (HCI) and computer-supported

Sons, 1987), 359; and Robert B. Bechtel,

cooperative work (CSCW) literature, where social frameworks

Environment and behavior: An introduc-

are commonly used in studying collaborative work. Frameworks

tion (Thousand Oaks): Pearson Prentice

Hall, 1997).

that, in terms of the criteria, appeared to be useful as a thinking

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

33

Table 1 Overview of the criteria that evolved in the search process.

Group

List of Criteria

1. The framework needs to address the social in relation to the material;

2. The framework needs to provide experienced people researchers with (new) perspectives of the

social, and offer designers handles to the social in analyzing and structuring user experience data;

Relational frameworks

2.1. The framework needs to provide handles of the social in terms of variables or ingredients that design

teams may use as anchor points in reading and interpreting user data;

3. The framework needs to point out key concepts of the social and material that design teams need to

pay attention to in building creative understanding of users’ experiences;

Special effect theories

3.1 The framework needs to be holistic in scope to support design teams in building broad understanding

of users’ experiences in the early phases of NPD;

4. The framework needs to offer design teams ways of interpreting and explaining user experience data

by revealing relationships and processes of the social and material;

5. The framework needs to facilitate seeing patterns and trends in user data, supporting design teams

in generating user insights and identifying opportunities for design.

Metaphors of the social

5.1 The framework needs to support teams in taking user experience data to a higher level of

understanding for identifying themes, patterns and trends in the data;

Metaphors of the social

6. The framework needs to offer multiple levels of description and explanation to support analysis of

user experience data in different phases of an empathic design process;

Catalogues of the social

7. The framework needs to be generally applicable to support design teams in transforming as well as

understanding users’ experiences;

Metaphors of the social

8. The framework should allow for use in a half-day session;

tool of the social in empathic design were tried out together with

Footnote 24 continued

multi-disciplinary design teams in industry. The researchers’ and

Tajfel and Turner (1979) introduced

the teams’ experiences in applying these frameworks led to new

Social Identity Theory, a theory of social

change that has been very influential in

criteria, which in turn focused the search process.

social psychology. The theory focuses on

The frameworks included in our study can be categorized

how social context affects self-concept

into five groups: (1) special effect theories, (2) relational frameworks,

and social behavior. People describe

(3) catalogues of the social, (4) metaphors of the social, and (5)

themselves differently and sometimes

scaffolds of context. An overview of the groups and our findings in

also behave differently in different

social contexts, for example, in front of

terms of new search criteria is presented in Table 1 and discussed

colleagues at work, or with family at

in the following paragraphs. The sequence in which the groups are

home. Social identity theorists distin-

discussed more or less delineates our search process.

guish two different classes of identity:

personal identity and social identity.

Special Effect Theories

Personal identity is the individual’s self-

The first category covers special effect theories that highlight one

concept derived from his/her attitudes,

memories, behaviors and emotions.

or a few concepts regarding behavior in social or material contexts.

Social identity is the individual’s

We found many of these theories in environmental psychology and

self-concept derived from perceived

in social psychology, ranging from mini-theories, which apply to

membership of social groups. People

specific phenomena, to more general theories, which apply to classes

have as many personal identities as

of behavior.22 An example of a mini-theory is the Ringelmann effect,

they have interpersonal relationships

that they feel engaged in. And they

which holds that an individual’s effort in a task decreases when

have as many social identities as

group size increases.23 Two examples of more general theories are

groups they feel they belong to. The

proxemics and social identity theory.24

34

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

Footnote 24 continued

In HCI and design, special effect theories have been

personal or social identity that is most

successfully used to envision how products and services might

salient at a given time shapes our

affect social practices and to confirm findings from people

concept of self and corresponding

research.25 In a design project about teens’ cliques, for example, the

behavior. See Hogg and Vaughan,

Social Psychology, fourth edition.

people researchers consulted literature about group structures to

25 Benyon, Turner and Turner, “Designing

determine whether they had overlooked roles in teens’ cliques.26

Interactive Systems: People, Activities,

In a project about baby care, the people researchers used literature

Contexts, Technologies.”

about parenting styles to develop criteria for segmentation of

26 Carolien E. Postma and Pieter Jan

families. However, we found that special effects theories were not

Stappers (2006), “A Vision on Social

particularly helpful thinking tools of the social in developing a

Interactions as the Basis for Design,”

CoDesign, 2:3, 139-55.

broad understanding of users’ experiences as a starting point for

27 Situated action studies the relation

identifying opportunities for product and service development,

between acting individuals and their

because they only address part of human behavior in context. This

changing environment. The term “situ-

finding led to a new search criterion: The framework should be holistic

ated action” was first introduced by Lucy

in scope to support design teams in building broad understanding of users’

Suchman in her book “Plans and Situated

Actions” (1987) to stress the emergent,

experiences in the early phases of NPD (criterion 3.1).

improvisatory character of people’s activi-

ties. The book is a critical response to the

Relational Frameworks

information-processing paradigm, which

Relational frameworks describe the nature of the relationships

models people as cognitive systems

between people and their environment. They are generic frameworks

that pursue action after having set goals

and having developed plans. Suchman,

in the sense of conceptual approaches or theoretical perspectives.

taking an ethnomethodological stance,

Three examples of relational frameworks are situated action,27

argued that the structure of activity is

behavior settings theory,28 and Gibson’s theory of affordances.29

not planned, but evolves in response to

In addition, actor network theory and Battarbee & Koskinen’s

real-world situations that are inherently

framework of co-experience may be seen as falling into this

dynamic. Suchman does recognize the

category.30

existence of plans, but merely as one

of several resources within the situa-

For social scientists, relational frameworks have provided

tion that may shape an activity. Goals,

new perspectives on studying and interpreting human behavior.

she argues, are defined in retrospect.

Stressing the improvisational nature of human action, situated action

Suchman uses the example of canoe-

invited researchers to study the moment-by-moment organization

ing in explaining the idea of Situated

of an activity in real settings. Behavior settings theory introduced

Action: “In planning a series of rapids in

a canoe, one is very likely to sit above

the idea of environmental units that direct human behavior and

the falls and plan one’s descent. (…) But,

prompted researchers to identify and study relations between extra-

however detailed, the plan stops short

individual patterns of behavior and settings that are specified in

of the actual business of getting your

time and place. The concept of affordances provided a lens to look

canoe through the falls. When it really

at relations between properties of an environment and individuals’

comes down to the details of responding

to currents and handling a canoe, you

history, abilities, and intentions.

effectively abandon the plan and fall

For designers, however, these relational frameworks are

back on whatever embodied skills are

generally more difficult to apply because they typically do not offer

available to you.” See Lucy A. Suchman,

“handles” of the social. They provide only very limited guidance as

Plans and situated actions: The problem

to what aspects of behavior and environment should be considered

of human machine communication

in studying social phenomena because the frameworks do not

(New York): Cambridge University Press,

1987); and Bonnie Nardi, “Studying

specify variables or ingredients of the social. That designers seek

Context: A Comparison of Activity Theory,

this guidance is nicely illustrated by the shift of meaning of Gibson’s

Situated Action Models and Distributed

concept of affordances in HCI and design, where an operational

Cognition,” Context and Consciousness:

redefinition has evolved that sees affordances as “opportunities

Activity Theory and human-computer

for action suggested by an object,” which is far removed from its

interaction, ed. Bonnie A. Nardi

(Cambridge: MIT Press, 1996), 69.

original meaning. We therefore concluded that the thinking tool of

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

35

the social should provide “handles” of the social, which are the variables

28 Behavior Settings theory focuses on the

or ingredients that design teams may use as anchors in reading and

relationship between extra-individual

interpreting user data (criterion 2.1).

behavior and environmental units.

From detailed field observations Barker

(1968) found that human behavior is

Catalogues of the Social

not randomly distributed across time

“Catalogues” in this case means the maps of people’s behavior in

and space; “the inhabitants of identical

their social and material contexts. Such maps often are developed on

ecological units exhibit a characteristic

the basis of personal experience and/or empirical research. Seminal

overall extra-individual pattern of

work in this regard is the concept of pattern language proposed by

behavior,” he argued (Barker, 1968). In

a school class, for example, teacher

Alexander, Ishikawa, and Silverstein.31 The book offers a typology

and students behave “school class.”

of solutions that architects might incorporate in the development

In the supermarket people, including

of towns and buildings. The typology is presented as a system

the teacher of the school class, behave

of patterns that describe relationships between people and their

“supermarket.” And during a meeting of

surroundings and that were developed based on years of experience

the teachers of the school, the teachers

behave “staff meeting.” Barker called

with building and planning. Each pattern, in essence, reports a

the physical-behavioral units “behavior

problem, the context in which the problem occurs, and a solution to

settings.” Behavior settings are “stable,

the problem. For example, in the context of designing a family home,

extra-individual units with great coercive

Alexander et al. suggest that architects may address the problem of

power over the behavior that occurs

creating quiet and private spaces for parents by designing the family

within them.” See Roger G. Barker,

home in such a way that the continuum of spaces where children live

Ecological Psychology: Concepts and

methods for studying the environment

and play does not include the parents’ realm.32

of human behavior (Stanford: Stanford

In HCI and CSCW, social scientists have seized the idea of a

University Press, 1968).

pattern language as a way to structure and document ethnographic

29 Gibson proposed an ecological

field data and to produce guidelines for design that transcend the

approach to perception. In his book

particularities of the data, but that are still grounded in the real

‘The Ecological Approach to Perception’

(1979), he described a new paradigm for

world.33 Crabtree, Hemmings, and Rodden, for example, have

understanding human activity in context,

developed a framework for identifying patterns of social action and

focusing not on the actor and (part of)

technology use in domestic settings.34 Martin, Rodden, Rouncefield,

his/her environment as independent

Summerville, and Viller have used patterns from ethnographic user

things, but rather on the relations

research to inform the development of computer systems.35

between actor and environment. He

For our goal of developing patterns for considering the

introduced the term “affordances” to

mean the full set of potential actions

social in empathic design, we had neither decades of experience

that an environment holds in store for a

from practice nor extensive field data to rely on. In addition,

particular actor. For example, a ladder

because patterns are context-specific, they might not be helpful in

affords an adult to climb up and down,

envisioning radically new situations of product and service use in

but it does not afford a baby to climb up

empathic design. A framework for the social in empathic design

and down. Information about affordances

is available to the actor’s senses.

needs to be generally applicable to various situations of product and

The actor’s attunement to particular

service use, including situations that do not yet exist.

affordances is determined by his/her

A possible solution to both issues is to take a “top-down”

needs and intentions, personal history

approach, rather than a “bottom-up” approach in developing

and context. See James J. Gibson, The

patterns. Kelley, Holmes, Kerr, Reis, Rusbult, and Van Lange’s “An

ecological approach to visual perception

atlas of interpersonal situations” is a good example of a pattern

(Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1979); and

Gerda Smets, Vormleer: De paradox

language that was developed using a top-down approach.36 They

van de vorm (Amsterdam: Uitgeverij

developed patterns by describing and analyzing common social

Bert Bakker, 1986). Several people

situations using one theoretical framework: interdependence theory.

have elaborated on Gibson’s concept of

The resulting atlas presents both the framework and the patterns.

affordances for understanding the social.

Kelley et al.’s atlas does not address the social in relation to the

Gaver, for example, introduced the term

“Affordances for Sociality” to

material, but the idea of combining both a framework and patterns

36

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

is interesting because it provides both the perspectives and the

Footnote 29 continued

handles to the social that we are looking for: It offers a thinking tool

refer to the possibilities offered by the

of the social that enables design teams to envision radically new

physical environment for social activity.

An example of affordance of sociality is

situations of product and service use that go beyond the scope of the

the table setting presented in figure 1.

context-specific patterns, as well as concrete examples of the social in

See Gaver, “Affordances for Interaction:

terms of patterns that help design teams think about the framework.

The Social is Material for Design,”

Such patterns could be developed once a suitable framework has

111-29. Valenti and Good used Gibson’s

been found.

ecological approach to perception as a

As a new search criterion, we conclude that the framework

framework for studying social interaction.

They introduced the term “Social

needs to be generally applicable to support design teams in both

Affordances,” meaning the possibilities

understanding and transforming users’ experiences (criterion 7).

for action that people offer one another,

and the role of other people in pointing

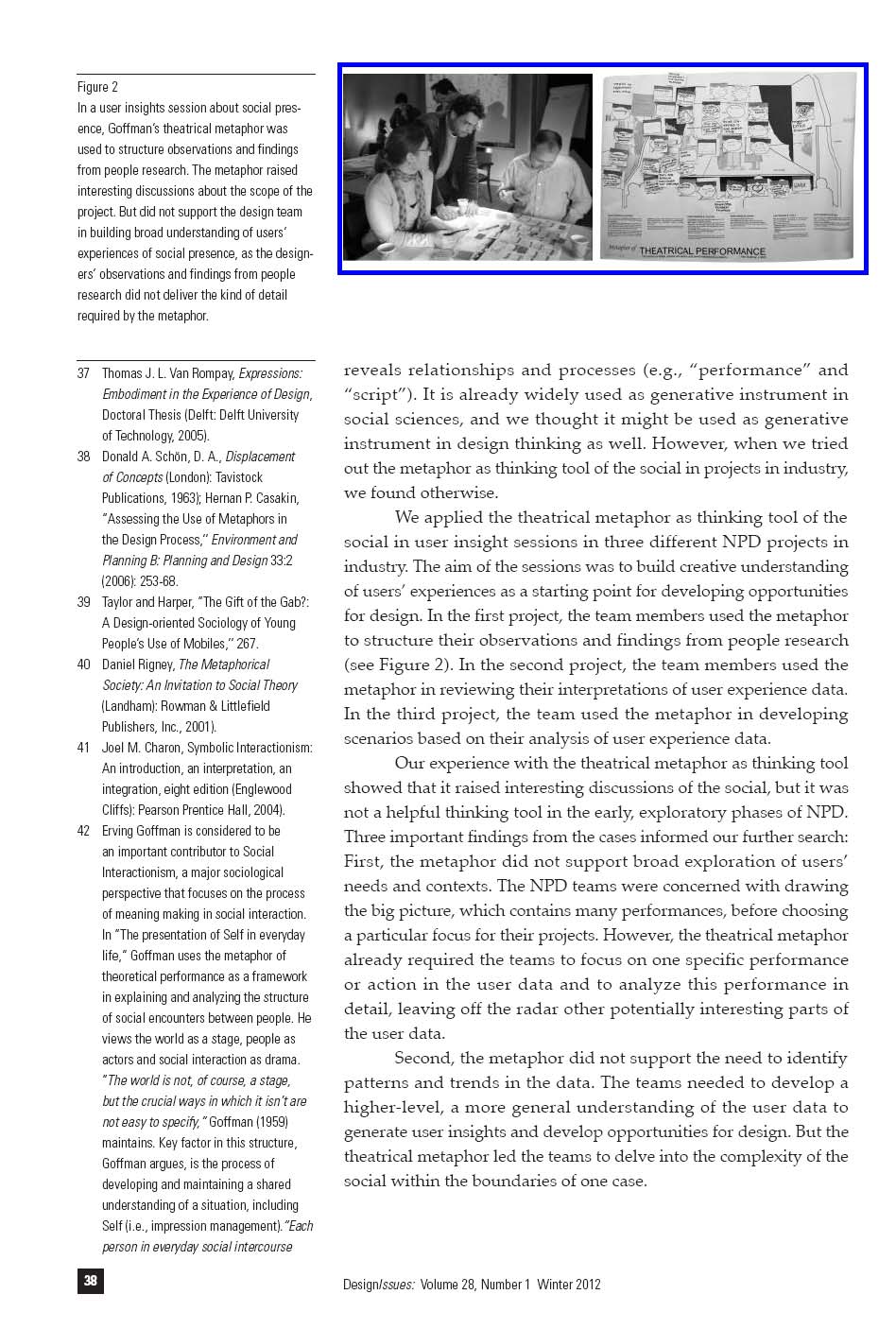

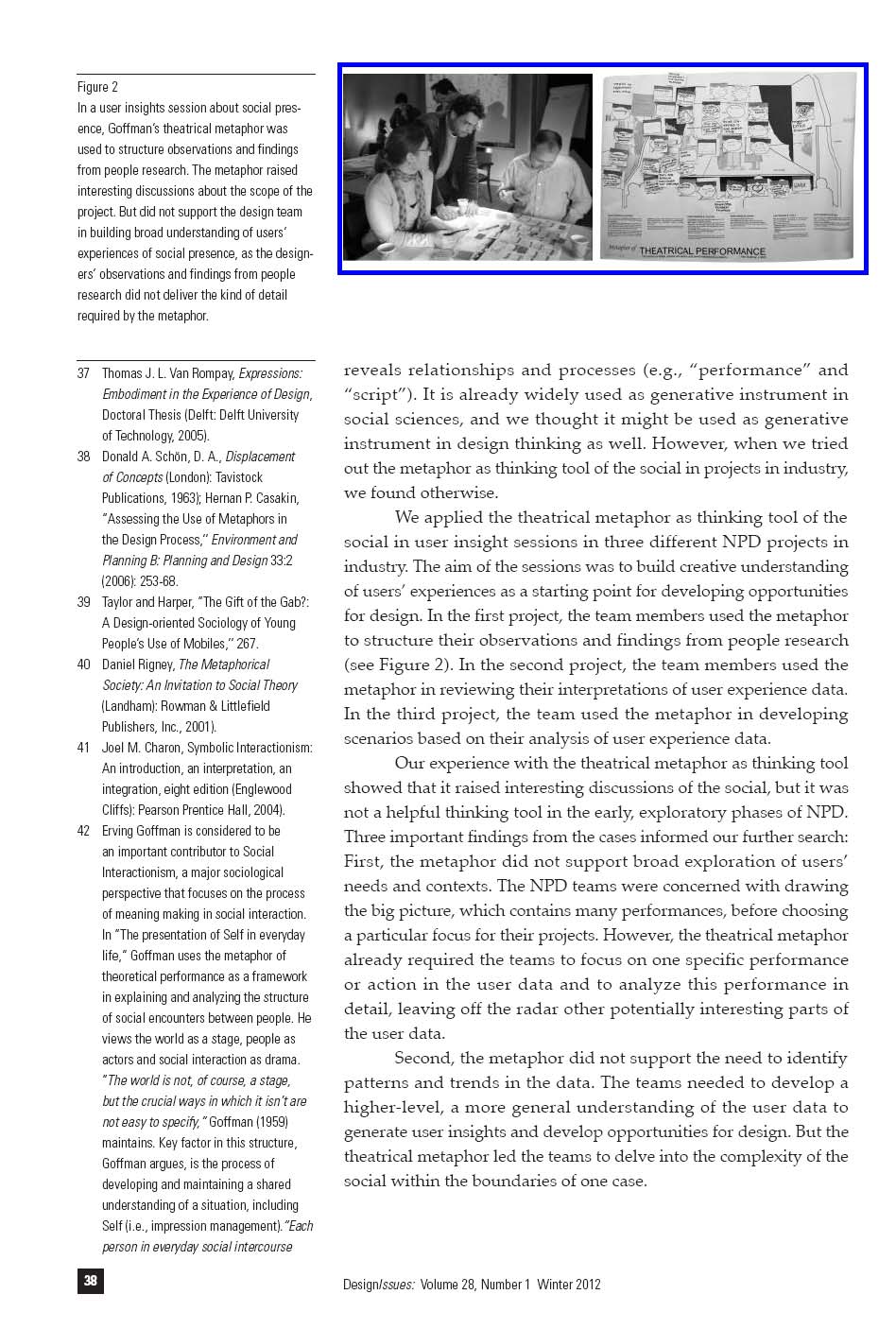

Metaphors of the Social: The Theatrical Metaphor

out new affordances. People may, for

The third category is metaphors. Metaphors are used for

example, afford one another comforting,

fighting, or play. See Stavros S.

understanding one concept in terms of another. In the field of

Valenti and James M. M. Good,

design, two important uses of metaphor may be distinguished: (1)

“Social Affordances and Interaction I:

metaphor as an expressive tool,37 of which the desktop metaphor

Introduction,” Ecological Psychology 3:2

in computing is a well-known example; and (2) metaphor as a

(1991): 77-98.

generative instrument, which means transferring the structure of one

30 Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social:

concept to the other to develop new ways of seeing both concepts.38

An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005);

The latter sense of metaphorical thinking is also used in social

Katja Battarbee and Ilpo Koskinen,

sciences in interpreting and explaining social phenomena. Taylor

“Co-experience: User experience as

and Harper, for example, used Mauss’s metaphor of gift-giving to

interaction,” CoDesign 1:1 (2005): 5-18.

interpret their observations of teenagers’ text messaging practices.39

31 Christopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa

Other examples of metaphors used as generative instruments in

and Murray Silverstein, A Pattern

Language (New York: Oxford University

social sciences are game metaphors, such as the prisoner’s dilemma

Press, 1977).

and the theatrical metaphor.40 For us, Goffman’s use of the theatrical

32 Ibid.

metaphor is of particular interest.

33 John Hughes and others, “Patterns

Gof man, a sociologist and important contributor to symbolic

of Home Life: Informing Design for

interactionism, is renowned for his dramaturgical analysis of social

Domestic Environments,” Personal and

encounters.41 In “The presentation of Self in everyday life,” he used

Ubiquitous Computing 4:1 (2000): 25-38.

34 Andy Crabtree, Terry Hemmings and

the theatrical metaphor as a framework in analyzing and explaining

Tom Rodden, “Pattern-based Support for

the structure of social encounters, viewing the world as a stage,

Interactive Design in Domestic Settings,”

people as actors, and social interaction as drama.42 The metaphor

in Proceedings of the 4th Conference

prompts questions such as: Who is the performer, and who is the

on Designing Interactive Systems (New

audience? What is front stage, and what is back stage? What does

York: ACM Press, 2002): 265-76.

35 David Martin and others, “Finding

the décor look, hear, smell, and feel like? What are the plot outline

patterns in the fieldwork,” in Proceedings

and the run time of the performance? Which tools of expression are

of the 7th Conference on European

used in the performance, and for which goal? What are the (social)

Conference on Computer Supported

roles of the performers? What are the performers’ motivations,

Cooperative Work (Norwell:

emotions, beliefs, and attitudes in relation to the performance?

Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2001),

How are the performers’ behaviors on stage different from their

39-58; David Martin and others,

“Patterns of Interaction: A Pattern

behaviors backstage?

Language for CSCW,” www.comp.

Examining metaphors on the basis of literature suggests

lancs.ac.uk/research/projects (accessed

that Goffman’s framework would be an excellent thinking tool of

August 4, 2010).

the social for empathic design: The framework is holistic in scope;

36 Harold H. Kelley and others, An atlas of

identifies key concepts and ingredients of the social and material

interpersonal situations (Cambridge UK:

Cambridge University Press, 2003).

(e.g., “front stage-back stage” and “tools of expression”); and

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

37

Third, the theatrical metaphor required too much time to

Footnote 42 continued

understand and apply in the context of a user insights session. The

presents himself and his activity to

team members of the third project indicated that they preferred not

others, attempts to guide and control

the impressions they form of him, and

to use the metaphor because they thought it was too difficult to

employs certain techniques in order to

grasp within the time frame of an insights session. Similarly, in the

sustain his performance, just as an actor

first project, the metaphor often put team members out of their depth

presents a character to an audience,”

in a way that paralyzed the creative process. Three new criteria were

he explains. See Erving Goffman, The

drawn from these findings:

presentation of Self in everyday life

• The framework needs to offer multiple levels of description

(New York): Anchor Books Doubleday,

1959); and Joel M. Charon, Symbolic

and explanation to support analysis of user experience data in

Interactionism: An introduction, an

different phases of an empathic design process (criterion 6).

interpretation, an integration, eight

• The framework should support teams in taking user experience

edition (Englewood Cliffs): Pearson

data to a higher level of understanding for identifying themes,

Prentice Hall, 2004. Important concepts

patterns, and trends in the data (criterion 5.1).

of the metaphor include:

• Performance – In their performance, the

• The framework should be applicable within a limited time, such

performers consciously or unconsciously

as a half-day session (criterion 8).

project their roles and their definition

of the situation to the audience. The

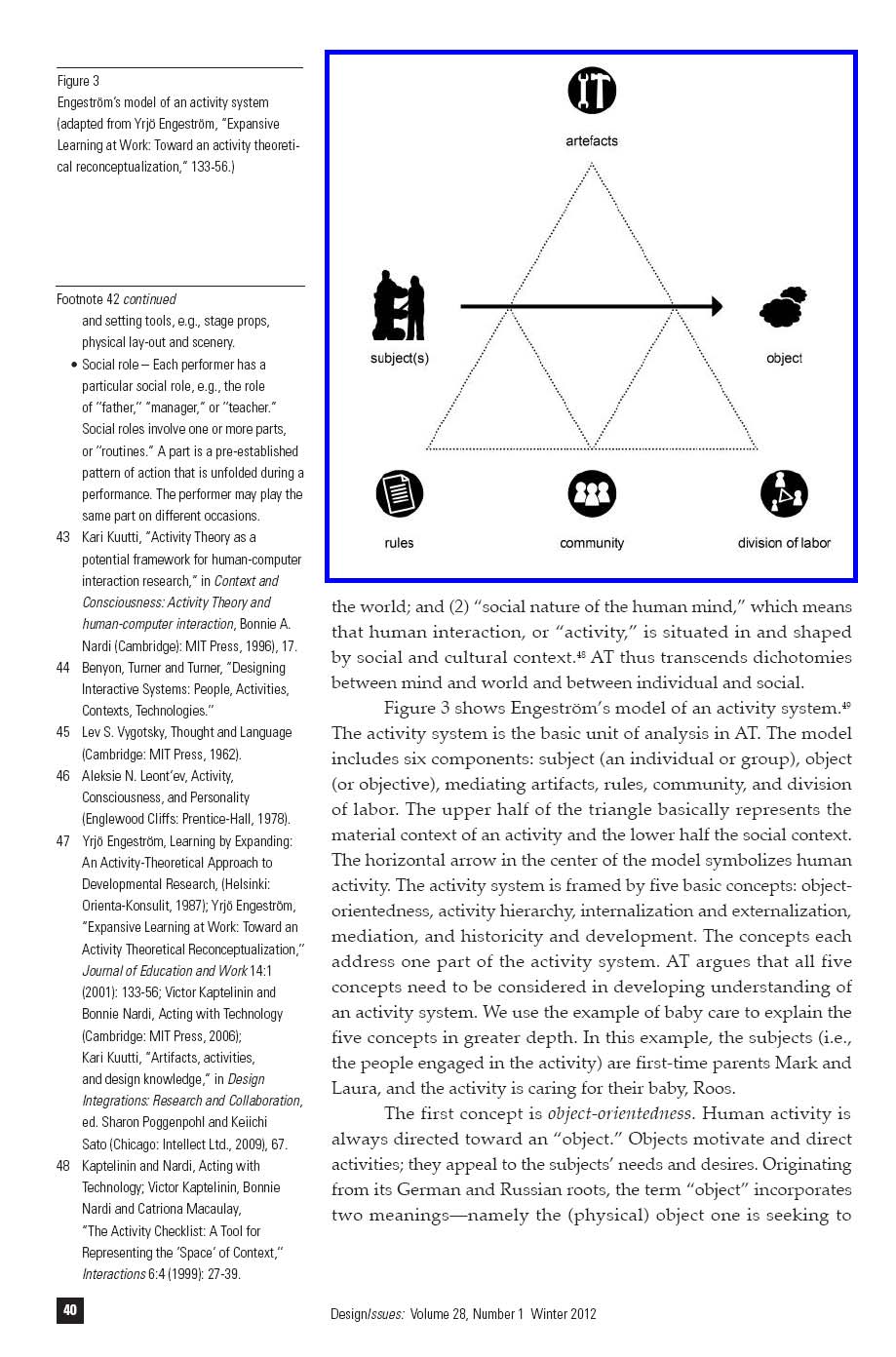

Scaffolds of Context: Activity Theory

audience observes the performance and

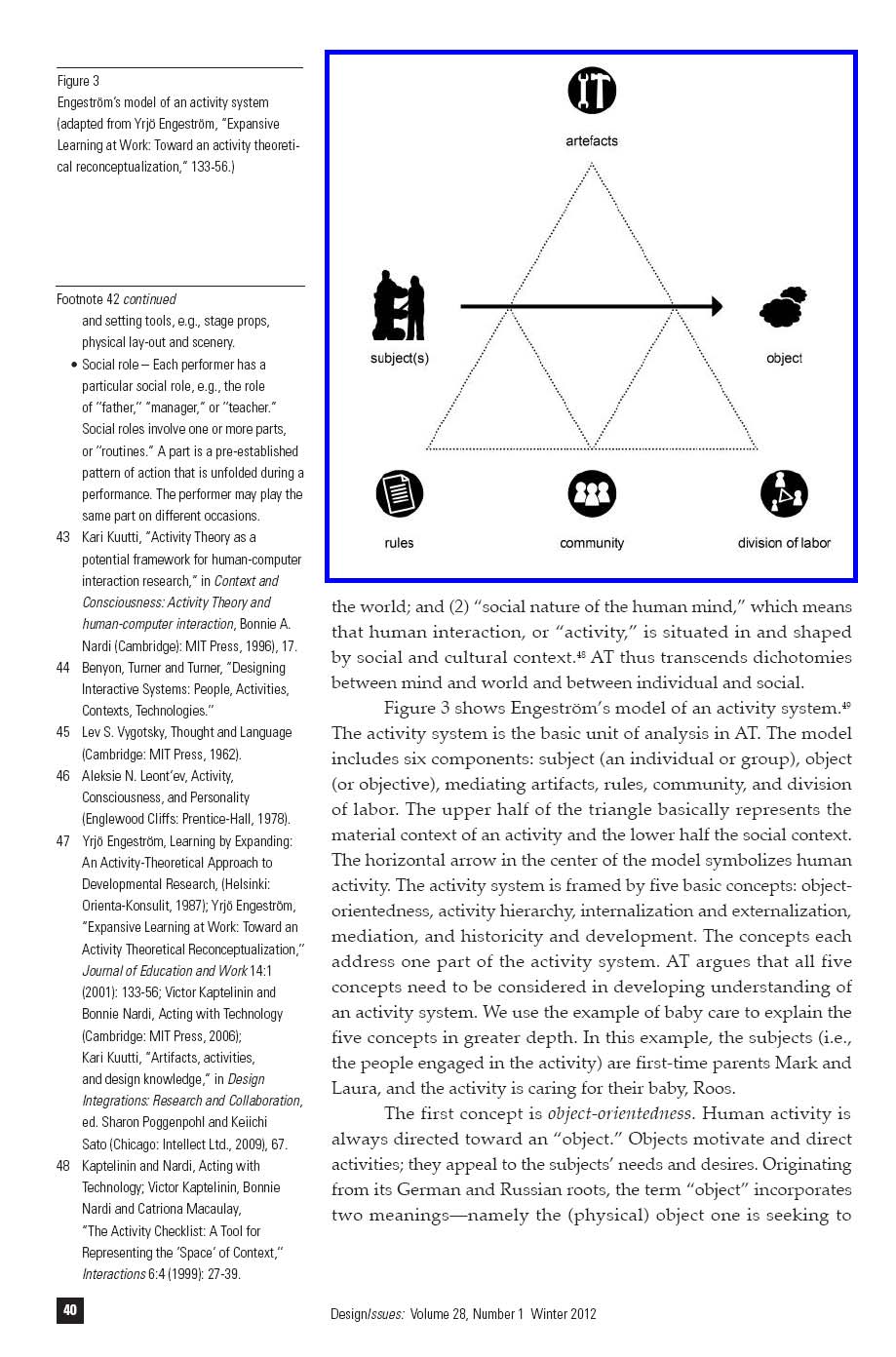

Our search concluded with activity theory (AT). AT is a framework

makes inferences about the performers

for describing and explaining the structure, development, and

(e.g., their motives, emotions, beliefs,

attitudes) and the performers’ definition

social-cultural context of people’s activities. The framework points

of the situation. The roles of performer

out concepts of the social and the material that we need to take into

and audience may switch continuously.

account in developing an understanding of the what, how, and

• Location – Front stage is where the

why of people’s behavior in their social-cultural context.43 It spurs

performance takes place and both

questions such as: What is the activity? Who are the people involved

performers and audience are present.

Back stage is where the performers are

in the activity? Why do they do the activity (i.e., what is their

present, but the audience is not. Here

objective)? What actions and operations do they do in pursuing the

the performers can relax and behave out

objective? What tools do the people use in achieving the objective?

of character. The waiter of a restaurant

How do these tools mediate their activity? What roles do the people

(i.e., performer), for example, may be

have in pursuing the objective? How do the people work together in

very polite and charming in front of the

the activity; what are their rules, norms, and procedures? How does

customer who complains about the food

(i.e., audience). But once back in the

the activity develop over time?

kitchen (i.e., back stage), the waiter and

his colleague may imitate the customer

Activity Theory in a Nutshell

and make fun of him. Note that the back

Although called a theory, AT is best described as paradigm of human

stage in one performance could be the

activity.44 AT has its roots in early twentieth century Russia, where

front stage in another performance.

In the example, the waiter and his

its first foundations were laid by Lev Vygotsky in developing his

colleague in the kitchen also perform in

cultural-historical psychology.45 AT was further developed into a

front of each other.

conceptual framework by his colleague, Alexei Leont’ev.46 Only in the

• Script – Prescribes the performance:

early 1980s, after seminal work on AT had been published in English,

What happens to whom, when, where,

did the conceptual framework become known internationally. In

how and why? How is tension built up?

1987, Yrjö Engeström presented a framework of human activity in a

When does the scenery change?

• Tools of expression – Vehicles for

social-cultural context that builds on Leont’ev’s AT.47

conveying signs that the performers,

Two fundamental ideas lie at the heart of AT: (1) ”Unity of

either or not consciously, use in their

consciousness and activity,” which is the idea that the human mind

performance. There are three types of

can only be understood in the context of people’s interaction with

tools: appearance tools, e.g., clothing,

posture, age; behavior tools, e.g., facial

expressions, attitude and gestures;

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

39

transform in the activity (e.g., the stone that a sculptor is shaping)

and the objective that one is aiming to achieve (e.g., the sculpture

that the artist has in mind while shaping it).50 Mark and Laura’s

object of baby care is a healthy and happy baby Roos. Mark and

Laura’s community of baby care includes their parents, their close

friends Bram and Marije, the daycare center, and the child health

center. The concept of object-orientedness helps us to develop

understanding of the ultimate “why” of their actions in caring for

baby Roos.

Note that from an AT perspective, exploratory design

research should not be about uncovering people’s latent needs,

but about following objects that motivate people’s activities. This

perspective may shed a different light on the development of

tools and techniques that are frequently used in empathic design,

such as design probes,51 generative techniques,52 and experience

prototyping.53

The second concept is activity hierarchy. An activity can be

deconstructed into actions and lower-level operations. Actions

(similar to “tasks” in HCI) are directed toward goals (e.g.,

constructing a sentence to convey a message). Actions and goals

are conscious. Operations, meanwhile, are routinized or automated

behavioral routines and are typically unconscious (e.g., typing, or

switching gears when driving). Caring for baby Roos involves both

actions and operations, including singing a lullaby, changing her

diapers, taking her to the health center, and getting up at night to

feed her.

The levels of an activity are not fixed. Actions may become

automatic operations, and operations may become conscious actions.

In the case of Mark and Laura, for example, changing diapers used

to be a conscious action, but then it gradually turned into a routine

operation with practice. At one point, the operation of changing

diapers had become a conscious action again when Mark had

mistakenly bought diapers that are fastened in a different way.

The third concept is internalization and externalization. AT

distinguishes between internal, mental activities and external

49 Engeström, “Expansive Learning at

activities and argues that one cannot be understood without the

Work: Toward an Activity Theoretical

Reconceptualization,” 133.

other because they transform and influence one another.54 External

50 Victor Kaptelinin, “The Object of Activity:

activities become internalized when people learn to do an activity

Making Sense of the Sense-Maker,”

in the head without using any physical aids. To illustrate, Mark

Mind, Culture and Activity 12:1 (2005):

and Laura initially needed to figure out what made Roos cry. After

4-8; Yrjö Engeström and Frank Blackler,

a few weeks, they started to recognize and distinguish her cries

“On the Life of the Object,” Organization

12:3 (2005): 307-30.

and immediately knew what action to take. Internal activities are

51 Mattelmäki,

Design Probes,

externalized when an activity is too difficult to do without physical

Doctoral Thesis.

aids, when the activity does not turn out right, or when people need

52 Sanders, “Generative tools for

to coordinate the activities in working together. For example, Roos

codesigning,” 3-12.

was ill and wouldn’t stop crying, despite all efforts to comfort her.

53 Buchenau and Fulton Suri, “Experience

Prototyping,” 424-33.

54 Vygotsky, Thought and Language.

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

41

At first, Mark and Laura did not understand what was wrong; they

again needed to figure out why Roos was crying and what action

to take.

55 Kaptelinin and Nardi, Acting with

Technology 2006; Kaptelinin, Nardi

The fourth concept is mediation. People’s activities are

and Macaulay, “The Activity Checklist:

mediated by artifacts, the division of labor, and rules. All three form

A tool for representing the ‘space’

more durable structures that persist across activities, time, and place.

of context,” 27-39; Kuutti, “Activity

The durable structures shape activities and at the same time are

Theory as a potential framework for

developed and transformed in activities. They reflect the experiences

human-computer interaction research,”

17; Engeström, “Expansive Learning at

of others who have pursued similar objectives or goals. Artifacts, or

Work: Toward an Activity Theoretical

“tools,” are thinking tools as well as physical tools that the subject

Reconceptualization,” 133-56; Nardi,

uses in pursuing his/her object. Mark and Laura’s tools of baby care

“Studying Context: A Comparison of

include a comforting lullaby, Roos’ bedroom, her favorite teddy

Activity Theory, Situated Action Models

bear, and a playpen. Rules refer to implicit and explicit norms and

and Distributed Cognition,” 69-102.

conventions that govern the relationship between the subjects and

56 Susanne Bødker, “Applying Activity

Theory to Video Analysis: How

their community. For example, the child health care center, which

to Make Sense of Video Data in

is part of Mark and Laura’s community of baby care, advised Mark

Human-computer Interaction,” in Context

and Laura to build up a strict day routine for the baby that follows a

and Consciousness: Activity Theory

sequence of four actions: feeding, playing, sleeping, and taking time

and Human-computer Interaction, ed.

for yourself. Mark and Laura are now trying to develop and adhere

Bonnie A. Nardie (Cambridge: MIT

Press, 1996), 147; Kuutti, “Activity

to such a routine. Division of labor is the organization of the subjects

Theory as a Potential Framework for

and their community in terms of roles and responsibilities. Laura

Human-computer Interaction Research,”

usually brings Roos to bed. She tries to establish a bedtime routine

17; Bonnie Nardi, “Activity Theory and

by feeding Roos upstairs just before bedtime. Mark thinks it is too

Human-computer Interaction Research,”

much trouble to feed Roos upstairs, so he leaves this up to Laura. In

in Context and Consciousness: Activity

the meantime he does some household activities.

Theory and human-computer interaction,

ed. Bonnie A. Nardi (Cambridge: MIT

The fifth concept is historicity and development. Activities

Press, 1996), 7.

change and develop over long periods of time, and understanding

57 Examples are: Patricia Collins, Shilpa

an activity requires tracing how the activity has developed in the

Shukla and David Redmiles, “Activity

past. Contradictions (or tensions) within or between activity systems

Theory and System Design: A View From

are sources of change and development.55 In Mark and Laura’s case,

the Trenches,” Computer Supported

Cooperative Work 11:1 (2002): 55-80;

a contradiction between subjects and community led to a change of

Morten Fjeld and others, “Physical

action: Mark and Laura changed Roos’ sleeping routine after friends

and Virtual Tools: Activity Theory

pointed out that Roos may get used to sleeping in her parents’

Applied to the Design of Groupware,”

bedroom and may not learn to sleep on her own.

Computer Supported Cooperative Work

11 (2002): 153-80; and Kristina Lauche,

AT as Thinking Tool of the Social for Empathic Design

“Collaboration Among Designers:

Analysing an activity for system

Prominent researchers in HCI and CSCW, including Suzanne Bødker,

development,” Computer Supported

Kari Kuutti, Victor Kaptelinin, and Bonnie Nardi, have propagated

Cooperative Work 14 (2005): 253-82.

AT as a framework for HCI research and interaction design.56 AT

58 For example: Mervi Hasu, Critical

has been used in a number of cases to analyze ethnographic data

Transition from Developers to Users,

and formulate design requirements for social computing.57 Some

Doctoral Thesis (Helsinki: University

of Helsinki, Department of Education,

colleagues of Engeström have also used AT to study design practice

Center for Activity Theory and

and the effect of products on people.58 In both design research

Developmental Work Research, 2001);

and design practice, however, AT is still relatively unknown. Yet

and Sampsa Hyysalo, Uses of innovation:

our examination of the literature suggests that AT could be a very

Wristcare in the practices of engineers

powerful thinking tool of the social for doing empathic design in

and elderly, Doctoral Thesis (Helsinki:

NPD practice:

University of Helsinki, Faculty of

Behavioral Sciences, 2004).

42

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

• AT addresses the social in relation to the material (criterion

1). Unlike most theories in psychology, the framework

accounts for artifacts. And unlike many approaches in

the human factors discipline, the framework addresses

social practice, as well as individual behavior.59 Using AT

could therefore help design teams to get a sense of how the

products they design relate to people’s social practices.

• The framework identifies components of the social and

the material (e.g., division of labor and rules) that design

teams can use as anchors in reading and interpreting user

experience data (criterion 2.1). As studies in HCI and

CSCW have demonstrated, AT also provides experienced

people researchers with (new) perspectives of the social in

analyzing and structuring user data (criterion 2).60

• AT provides a comprehensive framework that emphasizes

key concepts of the social and the material that design

teams need to pay attention to in structuring and analyzing

user experience data (e.g., mediation and object-orient-

edness) (criteria 3 and 3.1).

• The framework offers design teams ways of interpreting

and explaining user experience data by revealing

relationships and processes, such as the dynamic levels of

an activity, historicity and development, and internalization

and externalization (criterion 4).

• AT supports design teams’ efforts to take user experience

data to a higher level of understanding and to identify

themes, patterns, and trends in the data. The idea of contra-

59 Frank Blackler, “Knowledge, Work

dictions can also help to identify opportunities for product

and Organizations: An Overview and

and service design (criteria 5 and 5.1).

Interpretation,” Organization Studies 16:6

• AT offers three levels of description and explanation (i.e.,

(1995): 1021-46; Yrjö Engeström, “Activity

theory as a framework for analyzing and

activity level, action level, operation level), supporting

redesigning work,” Ergonomics 43:7

design teams in building broad understanding of users’

(2000): 960-74.

experiences in the early phases of NPD, as well as more

60 Examples are: Bødker, “Applying

in-depth understanding in later phases of NPD (criterion 6).

Activity Theory to Video Analysis:

• Design teams can apply AT in building creative

How to Make Sense of Video Data in

understanding of various activities and contexts, including

Human-computer Interaction,” 147-74;

Collins, Shukla and Redmiles, “Activity

future situations of product and service use (criterion 7).

Theory and System Design: A View From

the Trenches,” 55-80; and Phil Turner,

The only criterion that AT does not meet is that of allowing for use

Susan Turner and Julie Horton, “From

under the time constraint of a half-day session (criterion 8). AT is

Description to Requirements: An Activity

often considered hard to learn and difficult to put into practice.61

Theoretic Perspective,” Proceedings

of the International ACM SIGGROUP

Given this reputation, we cannot expect design teams in practice

Conference on Supporting Group Work

to understand and use AT in a way that social scientists do. Thus,

(New York: ACM Press, 1999), 286-95.

the framework needs to be translated into more intuitive ways of

61 Nardi, “Activity Theory and Human-

building creative understanding of users’ experiences for design. In

computer Interaction Research,” 7;

the next section, we present an example of how we applied AT in

Benyon, Turner and Turner, “Designing

an NPD project.

Interactive Systems: People, Activities,

Contexts, Technologies.”

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

43

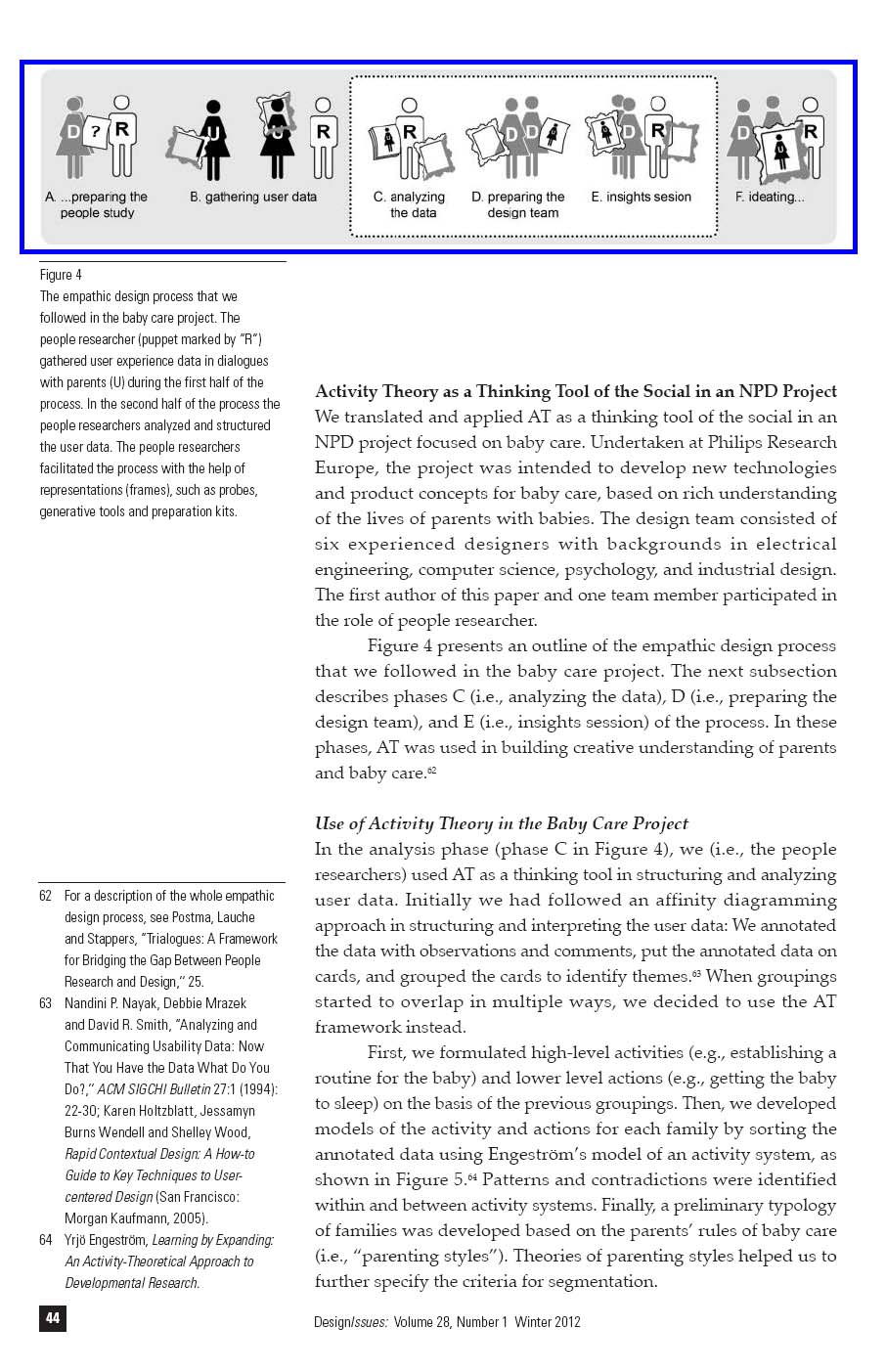

(3) by developing exercises that addressed concepts and components

of the activity system. For example, in one exercise about mediation,

the designers were asked to compare the things (or “artifacts”) that

used to help them fall asleep when they were young with the things

that helped the baby fall asleep. Each of the five exercises in the kit

addressed different concepts and components of AT.

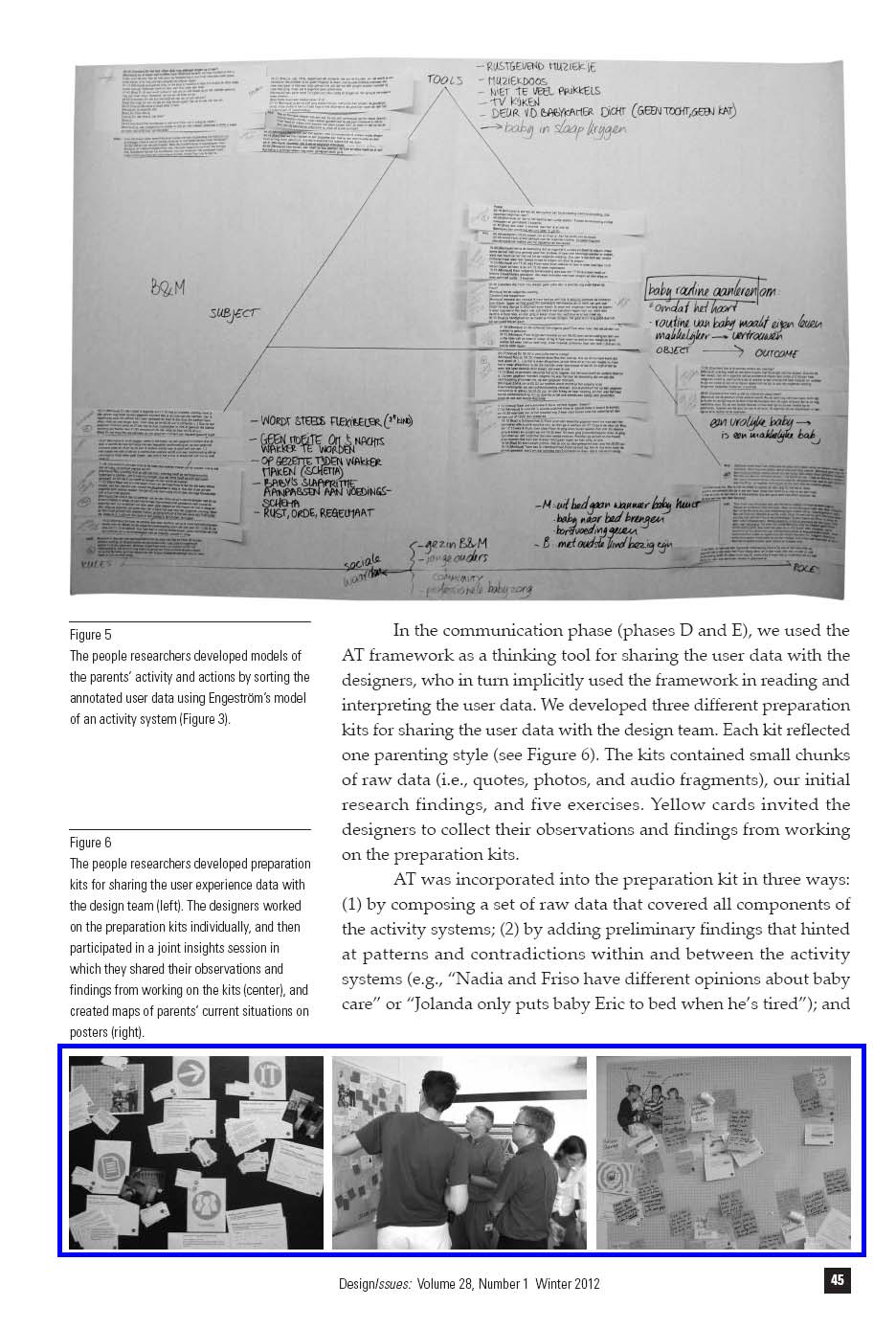

The designers worked on the preparation kits individually

for five days (phase D). A week later, the team members partic-

ipated in a collective insights session aimed at developing shared

understanding of baby care as a starting point for identifying

opportunities for technology and concept development. During the

session, the designers first discussed their observations and findings

from working on the preparation kits. Then they created maps of

parents’ current situations by structuring their observations and

findings on posters, and labeling groups of findings with themes.

Finally, they used the maps in generating ideas about possible

futures of baby care.

Findings from Using Activity Theory in the Baby Care Project

Trying out AT as a thinking tool of the social in the baby care project

revealed four important findings. In this section, we discuss these

findings and the implications for future projects.

Finding 1 – AT gave the designers, as well as the people researchers,

a platform for structuring, discussing, and sharing the rich user experience

data. In the analysis phase, using AT as a thinking tool in structuring

and analyzing the user data did not lead to many new or different

insights from the affinity diagramming approach. However,

we in the people researcher role felt that the framework greatly

enhanced the analysis process. We identified three advantages of

using AT: First, the basic concepts of the framework provided fresh

perspectives on how the data could be structured and interpreted.

For example, the concept of activity hierarchy raised questions of

where baby care and the actions involved in it begin and end. The

concept of object-orientedness required considering the parents’

long-term objectives of caring for their babies. And the idea of

contradictions prompted us to discuss the essence of the dilemmas of

baby care that parents face in everyday life. Second, the framework

provided a structured approach to organizing the user data. Having

structured the data using Engeström’s model of an activity system

facilitated identifying patterns and trends in the user data, and

sharing the user data with the design team. And third, AT offered a

structure for bringing in special effect theories, enabling us to specify

findings and insights.

In the communication phase, the design team implicitly used

AT as a thinking tool in reading and interpreting the user data.

The first success was that nearly all the designers worked on the

preparation kit. During the insights session, the components of the

46

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

activity system model were frequently used as anchor points in

discussing and structuring observations and findings. Components

were reflected in themes that were generated by the design team,

such as “Rituals help us to handle things we don’t like” (artifacts). And

in discussing the themes, team members noticed, for instance, how

parents’ communities could play a central role in positioning their

future product.

Finding 2 – It was difficult to implement and use AT in an integral

way. We agree with Kaptelinin that the strength of AT is in its

integration of concepts and components: When a design team uses

only part of the framework (e.g., the components of AT) and simply

ignores the rest, the team’s chances of overlooking opportunities and

constraints for design are likely to increase.65 But implementing and

using AT in an integrated way was difficult in the baby care project.

In the analysis phase, one concept was not used, and one

principle was used differently. As people researchers, we did not

use the concept of internalization and externalization. Internalization

and externalization processes were touched upon in parents’ stories

about baby care, but detailed analyses of these processes were

not needed at this stage for understanding the overall “what”

and “why” of baby care, and thus were omitted to save time.

We expect the concept of externalization and internalization to be

more useful in later stages of NPD, when product or service concepts

are developed.

The concept of historicity and development was used

differently. Rather than conducting a longitudinal field study,

which would not have been possible given the constraints of the

project, changes of activity systems were traced through how people

experienced them. However, the design team was able to learn about

development of baby care in later phases of the project, when people

studies were conducted that involved the same parents who had

participated in the exploratory people study.

In the communication phase, only one of five concepts of AT

surfaced in the designers’ observations and findings—namely, the

idea of contradictions within and between activity systems. One

designer observed that a couple had different parenting styles (or

rules): “Gert is rational. He reads books about baby care. Jolanda is more

intuitive, non-scientific,” he explained. And, looking at the division

of labor, another designer noted, “Laura has difficulties sharing tasks

with Mark.” The other four concepts, however, were not explicitly

addressed in the designers’ findings and discussions. Either the

designers did not use these concepts in generating findings, or they

65 Victor Kaptelinin, “Computer-mediated

used them implicitly.

Activity: Functional Organs in Social and

In future projects, designers and people researchers could

Developmental Contexts,” Context and

collaborate in a similar way as in the baby care project to ensure that

Consciousness: Activity Theory

the concepts and components of AT are integrally used in building

and Human-computer Interaction, ed.

creative understanding. However, the risk of this approach is that

Bonnie A. Nardi (Cambridge: MIT Press,

1996), 45.

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

47

designers might start using only part of the framework (e.g., the

components of the framework) in the belief that this one part is

the framework. A more profound approach would be to introduce

the components and the concepts of AT as inseparable parts of a

whole. This means that AT needs to be translated as an integrated

system for design, and not as a set of individual components and

concepts, as done here. The challenge is to find such a translation

of AT for design.

Finding 3 – The structure of the preparation kit did not support

drawing “the big picture.” In evaluating the insights session, the

team applauded the overall process followed in sharing the user

experience data. The team members were happily surprised by

both the quality and number of themes they had generated, in

comparison to their normal professional practice. They thought the

themes were “concrete” in that the themes provided clear starting

points for ideation. Most of the critical comments concerned the

preparation kit. The team members explained that the components

of the activity system had been useful in organizing the raw data

in the kit, but that it had been difficult to “get the full picture” of the

families and baby care because the components had been revealed

over time. The “full picture” had emerged only in discussing and

structuring observations and findings during the insights session.

In future projects, the team members would prefer an overview of

the families and baby care as an introduction to the preparation kit.

Finding 4 – Emotions are at the forefront of empathic design

but are rather obscured in AT. A more general concern that as people

researchers we noticed was the framework’s lack of attention to

the emotional domain. Empathic design stresses that rationality

and emotions both need to be addressed in building creative

understanding, but in AT, emotions are only implicitly addressed

in the concept of object-orientedness.66 When introducing AT as a

thinking tool in future projects, the role of emotions in object-orient-

edness must be further explicated to ensure that they are sufficiently

addressed in the analysis and communication of user data.

Conclusion

This paper reported our search for a theoretical framework that

people researchers and designers could use as a thinking tool of

the social in structuring and analyzing user experience data in

empathic design practice. We examined a variety of frameworks on

the basis of existing literature and then experimented with candidate

frameworks in NPD practice.

We identified eight criteria for assessing the usefulness

of frameworks for empathic design practice. Although the list of

criteria is not exhaustive, it does help us to draw attention to aspects

that researchers and designers need to consider when selecting a

framework for analyzing user experience data.

66 Kaptelinin and Nardi, Acting

with Technology.

48

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

The search process yielded five groups of frameworks: special

effect theories, relational frameworks, catalogues, metaphors, and

scaffolds of context. We found activity theory, as a scaffold of context,

to be the best fit between design teams’ needs and the frameworks’

offerings. AT is different from many other frameworks we studied

in that it transcends dichotomies between mind and world, and

between individual and social. Moreover, AT provides “handles” of

the social, as well as perspectives of the social, enabling designers

and experienced people researchers to join forces in analyzing user

experience data.

Testing AT as a thinking tool of the social in NPD practice, we

found that it provides designers, as well as people researchers, with

a platform for structuring, discussing, and sharing user experience

data. The study also revealed two findings that pose important

challenges for future research. First, AT addresses emotions merely

implicitly, whereas emotions are at the forefront of empathic design.

Thus, the role of emotions in AT needs to be further explicated when

using AT as a thinking tool in future empathic design projects. And

second, we translated AT for design in terms of a set of individual

concepts and components, but the actual strength of AT is in its

integration of concepts and components. In future projects, the

framework needs to be translated as an integrated system so that

designers can use the framework to its full potential.

Acknowledgements

This research was partly funded by Philips Research Europe. We

thank Elly Zwartkruis-Pelgrim and Boris de Ruyter for valuable

comments and advice. We also express our thanks to the project

teams for collaborating in the case studies, and to the families for

participating in our people research.

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

49