Trashion: The Return of the Disposed

Bahar Emgin

That objects lead “social lives” of their own as they move

through their biographies and undergo successive shifts in their

commodity status has already been acknowledged.1 Igor Kopytoff,

a professor of anthropology, introduced the notion of commod-

itization “as a process of becoming rather than as an all-or-none

state of being.”2 The idea that objects do not enjoy an unending

commodity status but that their lives are marked by the ebb and

flow between a commodity and non-commodity was central to

Kopytoff’s argument. As such, Kopytoff wrote, the biography of

an object was considerably similar to that of a person: occupying

different positions, leading diverse careers in the course of different

periods between a beginning and an end, being defined by

different regimes of value that are both economically and culturally

inscribed.3

In light of this argument, one could claim that the end of the

life of an object corresponds to the moment in which it is disposed

of. This disposal might take place in different forms and for

different reasons; however, in the most literal and common sense,

the life of an object ends in a trashcan in the form of waste. In this

1 The idea that objects lead social lives

moment, the object is left valueless in all the possible meanings of

was elaborated and discussed in detail

the term value: It can no more serve a function, it can on no account

in Arjun Appadurai (ed.). The Social

be exchanged for anything else, and it can by no means engage in

Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural

the processes of signification to connote and endow its user with

Perspective, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press, 2003).

specific social values.

2 Igor Kopytoff, “The Cultural Biography of

This article is about those objects that are recreated from

Things: Commoditization as Process,” in

trash through the process of upcycling. Upcycling is a term used by

The Social Life of Things: Commodities in

architect and designer William McDonaugh and chemist Michael

Cultural Perspective, ed. Arjun Appadurai

Braungart and refers to “the process of converting an industrial

(Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press, 2003), 73.

nutrient (material) into something of similar or greater value, in its

3 Kopytoff, “The Cultural Biography of

second life.”4 I argue that design, in this instance, acts as a tool of

Things,” 66.

transformation and reintroduces into certain orders what was once

4 “Upcycle,” The Dictionary of Sustainable

deemed waste. This theory counters the argument that an object is

Management, http://www.sustainability-

dead once it is disposed of.

dictionary.com/u/upcycle.php, (accessed

Such a conceptualization of waste as “the degree zero of

January 6, 2010.)

5 Gay Hawkins and Stephen Muecke,

value” has been contested for some time in different disciplines,

“Introduction: Cultural Economies of

ranging from economics to environmental studies, but most partic-

Waste,” in Culture and Waste: The

ularly by those studying consumerism or material culture.5 To give

Creation and Destruction of Value, ed.

an example, recycling has been endowed with a wide variety of

Gay Hawkins and Stephen Muecke

economic, environmental, and moralistic claims. Gay Hawkins

(Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers,

2003), ix.

© 2011 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

63

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

elaborates on the changing meanings of waste disposal and the

evolving attributions of recycling in her article titled “Plastic Bags:

Living with Rubbish.” Referring to the work of Susan Strasser,

Hawkins argues that disposal was central to the logic of mass

production and hence should not be assessed as only particular to

consumerism in the twentieth century: “Mass production of objects

and their consumption depends on widespread acceptance of, even

pleasure in, exchangeability; replacing the old, the broken, the

out of fashion with the new. The capacity for serial replacement is

also the capacity to throw away without concern.”6 What Strasser

underlines in Waste and Want, and what Hawkins agrees with in

her article, is the idea that “the ethos of disposability” was fostered

by the “desire for possession or convenience” as early as the 1860s,

leaving behind all concerns for the afterlife of the trash.7 According

to this idea, the emergence of a consumer society in the 1950s

only made the joy of disposing, which was once a privilege of

the upper classes, accessible to the masses. Within the regimes of

value of mass production, disposal was coded as an act directed

toward renewal, restoration, and purification; thus, the process of

disposing was not yet loaded with moral or ethical connotations.8

On the contrary, with respect to the issue of disposability,

waste was handled merely “as a technical problem, something to

be administered by the most efficient and rational technologies of

removal.”9 Only through the rise of environmental movements in

the 1960s did the disposal of waste come to be loaded with negative

meanings and viewed through a moral framework. The enormous

quantities of waste accumulating in urban centers, Hawkins

writes in “Plastic Bags,” were not only taken as a threat to the

environment, but also as a sign of an individualistic, insensitive,

and hedonistic consumer society.10 Waste now became evil. If the

environment is to be saved from our destructive power, then waste

should be “managed,” Hawkins asserts.11 Consequently, recycling

gained its contemporary prominence “as virtue-added disposal . . .

disposal in which the self is morally purified, disposal as an act of

redemption.”12 Disposal in the form of recycling is now a moralistic

attitude through which we pay the debt we owe to the world.

6 Gay Hawkins, “Plastic Bags: Living

with Rubbish,” International Journal of

The new, growing trend of trashion can be assessed within

Cultural Studies 4:1 (2001): 9. For the

this framework of recycling. Trashion is defined in Wikipedia as

history of rubbish, see Susan Strasser,

“a term for art, jewelry, fashion, and objects for the home created

Waste and Want: A Social History of

from used, thrown-out, found, and repurposed elements. The

Trash (New York: Metropolitan Books,

term was first coined in New Zealand in 2004 and gained in usage

Henry Holt and Company, 1999).

through 2005.”13 The term is made from the combinations of the

7 Hawkins, “Plastic Bags,” 9.

8 Ibid., 10.

words “trash” and “fashion,” and its creation can be counted as

9 Ibid.

an example of upcycling. In short, “trashion is a philosophy and

10 Ibid.

an ethic encompassing environmentalism and innovation. Making

11 Ibid., 11.

traditional objects out of recycled materials can be trashion, as

12 Ibid., 14.

can making avant-garde fashion from cast-offs or junk. It springs

13 “Trashion,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Trashion (accessed January 6, 2010).

64

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

from a desire to make the best use of limited resources.”14 The most

outstanding examples of trashion can widely be found among the

booming fields of green or eco-friendly design or the do-it-yourself

(DIY) movement. Trashion emerges first and foremost as a claim to

fulfill the aforementioned moral and ethical responsibility, in the

same way that recycling or waste management are promoted as a

means of “assuaging our guilt about the planet, being virtuous for

the neighbors and engaging in a form of disciplinary individualism

that is both voluntary and coercive at the same time,” according to

Hawkins.15 By means of upcycling or trashion, waste can experience

a rebirth and therefore a second chance of being used and reinte-

grated into exchange or identification processes. Thus, not only

is the environment purified by upcycling, but people involved in

trashion, as both designers and users, are also ennobled by virtue of

their commitment to nature and humanity.

However, to consider either recycling or upcycling merely

as moral issues would be misleading. On the other side of the coin

is the business stemming from these practices; recyclers not only

ease their conscience through recycling; they also make a profit.

Recycling, as “the huge tertiary sector devoted to getting rid of

things, is central to the maintenance of capitalism; it doesn’t just

allow economies to function by removing excess and waste—it

is an economy, realizing commercial value in what’s discarded,”

Hawkins and Muecke write in Culture and Waste.16 In the same

manner, upcycling has already been turned into a business:

Certain designers labeled eco-friendly are earning money through

upcycling, competitions are organized around trashion, numerous

websites are devoted to promoting and selling upcycled objects,

and online and print resources explain how to upcycle at home. In

short, there is a whole sector of upcycling now.

Only mentioning the moral and economic aspects of upcy-

cling and arriving at a conclusion regarding the consequences of

it for consumer culture would be cutting corners. There is still

more complexity to the issue than appreciating upcycling for its ethi-

cal stance or blaming it for being only another means of commoditiz-

ing. What is left untouched in this account, Hawkins and Muecke

point out, and what is more promising for an analysis of trashion, is

the “cultural economy of waste” that “can work on different strata:

symbolic, affective, historical and linguistic.”17 First, as Hawkins

and Muecke point out, this approach requires an emphasis on the

“hierarchical, ordered, and systematic determinations of value.”18 In

addition, a new conception of waste, which does not handle rubbish

as valueless and evil, is required. Only from this perspective can we

acknowledge waste as an active agent in the regimes of value. For

14 Ibid.

this reason, I introduce in the following section the changing concep-

15 Hawkins, “Plastic Bags,” 12.

tions of waste that are central to my analysis of trashion.

16 Hawkins and Muecke, “Introduction,” x.

17 Ibid. xvi.

18 Ibid.

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

65

1. Re-considering Waste

Contributions to the reconsideration of the notion of waste have, to

a great extent, come from the field of anthropology. Ethnographic

studies on gift and potlatch, burial rites and sacrifice, as well as

studies of consumption itself, influenced certain scholars and gave

rise to the questioning of old notions of waste and disposal. Kevin

Hetherington is one scholar who has considered the subject in light

of the studies on disposal by Mary Douglas, Roland Munro, and

Michael Thompson. Hetherington begins his analysis with a refusal

to see the concept of disposal as “the last act that leads inexorably

to a closure of a particular sequence of production-consumption

events.”19 Disposal for him lies at the heart of consumption and is as

central as the accumulation of objects to “managing social relations

and their representation around themes of movement, transforma-

tion, incompleteness, and return.”20 In this respect, Hetherington

writes that a spatial dimension is added to the issue of disposal,

and it becomes a matter of “placing” rather than discarding:

[D]isposal is a continual practice of engaging with making

and holding things in a state of absence, [with] any notion

of return (beyond simple equations of return with green

recycling), or [with] any notion of understanding how

something can be in a state of abeyance or “at your

disposal” and what the effects of that might be.21

Once the linear passage from production to consumption and lastly

to disposal is broken, the role of disposal in the processes of both

individual and social ordering becomes apparent. Disposal is not an

end to these processes in succession, but a matter of putting things

in a state of absence, invisibility, or remoteness—either metaphori-

cally or literally—through a process of valuation, and in this manner,

disposal—keeping certain things as “matter out of place”—func-

tions to stabilize the processes of ordering, Hetherington writes.22

However, the discussion at this level is quite structuralist, according

to Hetherington, and is directed toward maintaining a definite and

stable social order. The significance of disposal for consumption can

only be assessed if disposal is viewed “as a recursive process.”23 That

19 Kevin Hetherington, “Secondhandedness:

Consumption, Disposal, and Absent

is, disposal is never complete; objects can never be disposed of 100

Presence,” Environment and Planning D:

percent, but they fluctuate between a state of absence and a state

Society and Space 22 (2004): 159.

of presence. The disposed always carries with it the possibility of

20 Hetherington, “Secondhandedness,” 157.

coming back: “Its capacity for translation remains as an absence just

21 Ibid., 159.

as much as when a presence is encountered.”24

22 Ibid.

In

Culture and Waste: The Creation and Destruction of Value, John

23 Ibid.

24 Hetherington, “Secondhandedness,” 162.

Frow deals with the issue of waste by opposing the theories that

25 John Frow, “Invidious Distinction: Waste,

handle it as “the degree zero of value” or “the opposite of value”

Difference, and Classy Stuff,” in Culture

or “whatever stands in excess of value systems grounded in use.”25

and Waste: The Creation and Destruction

He refers to the role of waste in constructing value in this way: “On

of Value, ed. Gay Hawkins and Stephen

Muecke (Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield

Publishers, 2003), 25.

66

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

the one hand it is residually a commodity . . . On the other hand, the

category of waste underpins any system of social distinction, as the

principle of uselessness that establishes a non-utilitarian symbolic

order.”26 Similar to that of Hetherington, the symbolic order or

the systems of value that Frow defines are far from being definite,

closed, and static structures. On the contrary, value is always referred

to as a “process, a movement, a cycle” being defined, contested, and

redefined over and over again.27 Within such a value system, waste

or rubbish retains its chance of return and is even bestowed with the

chance to define a completely new regime of value, disturbing the

orderings and classifications that are based on the preceding one.

For both Hetherington and Frow, waste—or the valueless—

can always reach a totally adverse state of high value, and even over-

value, and they both elucidate this possibility through references

to Michael Thompson’s Rubbish Theory. As Hetherington explains,

Thompson in his study defines three different classes of objects:

durable, transient, and rubbish. Durable objects are marked by their

high status and hence they are, in a manner of speaking, dignified;

transient objects cannot enjoy a life-long high status, and their value

decreases gradually over time; and rubbish, as the last category, can

by no means be valued: “They become blanks that can address not

only the question of value in the singular instance but also value

as a general category.”28 The status of objects in the categories of

both durable and transient is clearly defined; the codes that assign

these objects to their categories are fixed; and their value is under the

control of social agents who strive to maintain the existing ordering.29

However, the case for rubbish objects is different; they are free from

the control exerted on the other two categories. Hetherington writes

that they stand on “a blank and fluid space between the other two

categories, helping to maintain their separateness while also provid-

ing a conduit for objects to move back and forth into the regions of

fixed assumptions.”30 Hetherington criticizes Thompson’s classifica-

tion for its stress merely on exchange, which he says overlooks other

possible ways of valorizing an object (e.g., a sentimental valoriza-

tion). Nevertheless, for both Hetherington and Frow, the value of

Thompson’s classification lies in the manner in which it opens up a

dynamic space that allows a transition between categories and thus

transformations in status, which in turn introduces fluidity to value

systems. In light of Thompson’s classification, it becomes possible

to conceptualize rubbish as the “conduit of disposal rather than that

which is placed in the conduit.”31

At this point, Hetherington introduces a new metaphor and

places the door, rather than the dustbin, as the proper exemplar of

26 Frow, “Invidious Distinction,”26.

the conduit of disposal. “Not only do doors allow traffic in both

27 Ibid., 35.

directions when open, but they can also be closed to keep things

28 Hetherington, “Secondhandedness,” 164.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid., 165.

31 Hetherington, “Secondhandedness,” 164.

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

67

outside/inside, present/absent, at least temporarily and provision-

ally.”32 Thus, not only is the process of disposal flexible, but the

conduits of disposal are themselves fluid, undermining through

the process of transfer any possibility of stability in the regimes of

value used.

The passage of the objects through these conduits can end

either in de-commoditization, namely in prolonging the priceless

state of being—not at the level of zero value this time, but at the

level of such a high value that there can be no equivalent for it in

any exchange system or in commoditization. Commoditization, here,

would rather be referred to as re-commoditization since the object in

question had once been a commodity before it moved through the

conduit of disposal. Collection constitutes an example of the former,

while trashion provides an example of the latter. Hetherington also

refers to collection as a conduit of disposal:

Still, much collecting derives its meaning precisely from

this dynamic—the making of the reputation of an object

(and thereby its status and value) by making it visible,

recognisable, and “respectable” (including cult or subcul-

tural respectability with respect to kitsch). A cheap,

contemporary, utilitarian object can be disposed of by one

generation only to return later and be claimed as a design

classic by the next.33

Valorization through the conduit of collection is not performed at

the level of exchange value because the object of collection does not

gain an extensive exchangeability; on the contrary, its exchange-

ability for anything else is substantially restricted. Through this

process, the act of “singularization” can be pointed to as the creator

that counteracted the object’s commoditization. Singularization, as

defined and elucidated by Kopytoff, is a process by which things

are deprived of their commodity status through a withdrawal from

the sphere of exchange.34 The struggle between singularization and

commoditization begins at the very moment that the actual exchange

is accomplished— when the thing is stripped of its unquestionable

commodity status.35 From this moment on, the thing is vulnerable to

several processes of individual or collective singularizations, which

in turn deactivate it as a commodity and cause shifts in its biography.

For the waste, which has been left valueless, singularization

would not come to mean decommoditization but would mean that

the object is prevented from being commoditized; valorization occurs

in the form of sacralization.36 In this manner, the object is given value

at the level of symbolic exchange, as explicated by Jean Baudrillard

in For a Critique of the Political Economy of Sign; these objects of collec-

32 Ibid.

tion come to be valued—not within the exchange system itself but

33 Ibid., 165.

34 Kopytoff, “The Social Life of Things,” 74.

35 Ibid., 83.

36 Kopytoff, “The Social Life of Things,” 80.

68

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

personally with regard to the place it occupies within social relations;

it thus becomes invested emotionally rather than monetarily.37

In the following section, I concentrate on the issue of trashion

as a conduit of disposal and, offering examples, elaborate on the

consequences of such transformation for the issue of consumption.

Design as a Conduit of Disposal

Design has now turned into an indispensable aspect of market-

ing strategies, whereby products are inculcated with added value.

Thus, products can be differentiated in the market, tailored to the

presumed tastes and choices of socially and culturally differentiated

target groups. In this respect, it is not surprising that the world of

rubbish has become a treasure for design—a profession consider-

ably involved in the generation of value through a creative process.

In this treasure, we find not only objects that are disposed of, but

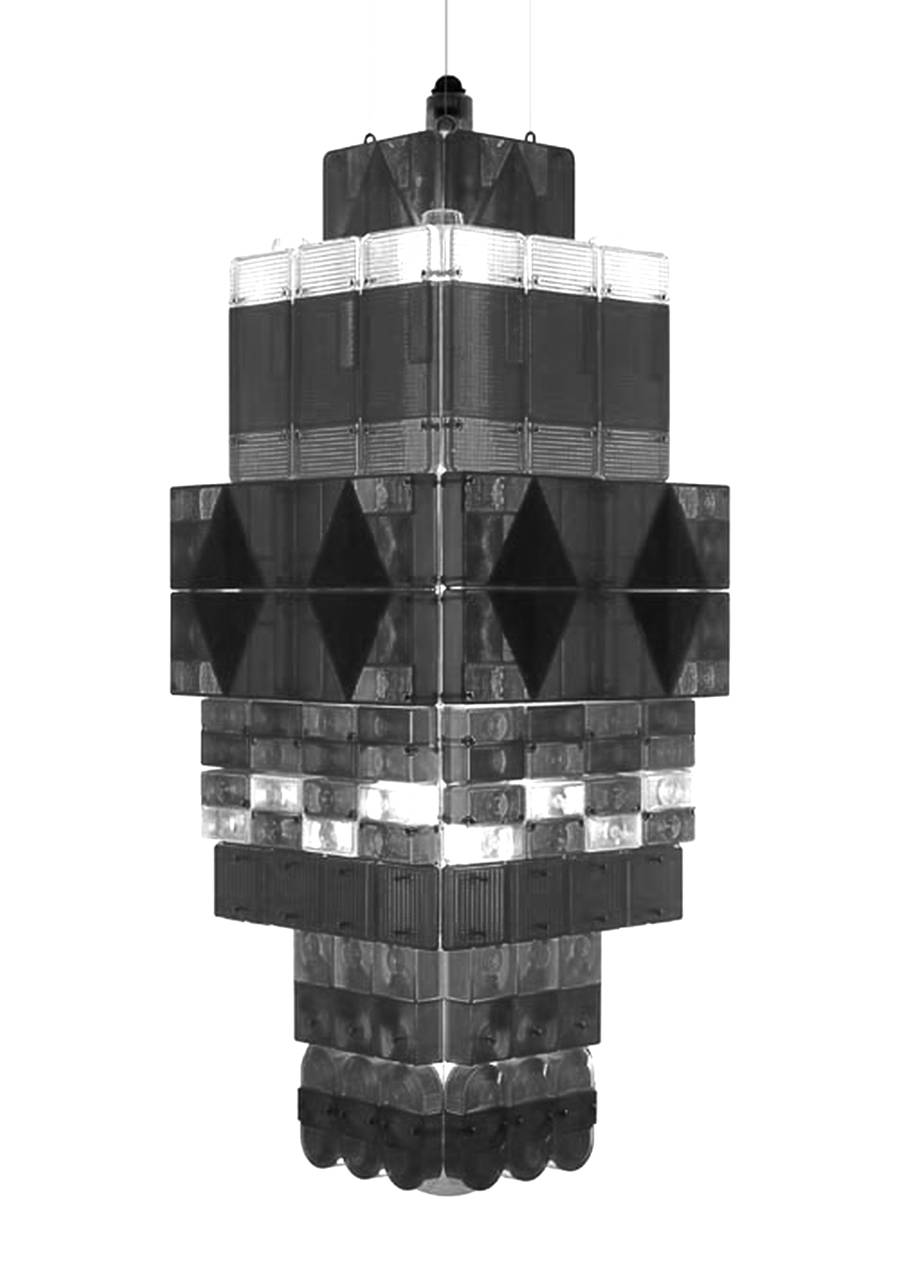

Figure 1

also forgotten styles, archaic technologies, and bits and pieces that

Tail Light by Stuart Haygarth.

never had the chance of acquiring any value. The magic wand of

design transforms these worthless, forgotten, neglected, and thrown

out items into precious pieces of aesthetic and moral value. In this

manner, design opens the door for the trashy to flow toward the

world of the valuable and valued.

The Tail Light (see Figure 1), by Stuart Haygarth, constitutes

a good example for the issue in question. The light is included on a

list of “25 Innovative Re-purposed Home Fittings Designs” gener-

ated by FreshBump, a social news medium devoted to the fields of

advertising, architecture, computer arts, graphic design, illustration,

industrial design, interior design, and photography.

The light, which, as its name suggests, is made of vehicle

tail lights, is promoted on the FreshBump website as follows: “A

busted tail light can you get pulled over, but it can also give you

a creative new light fixture. Artist Stuart Haygarth was inspired

by lenses covering vehicle lights, seeing in them something more

elevated than banal tail lights.”38 Vehicle lights, which have never

been considered objects in their own right, are now “elevated” to the

status of a designed object, with an unexpected increase not only in

their aesthetical attributes but also in their price. Thus, this trivial,

insignificant, plastic thing is successfully commoditized by flowing

in the opposite direction in the conduit of disposal.

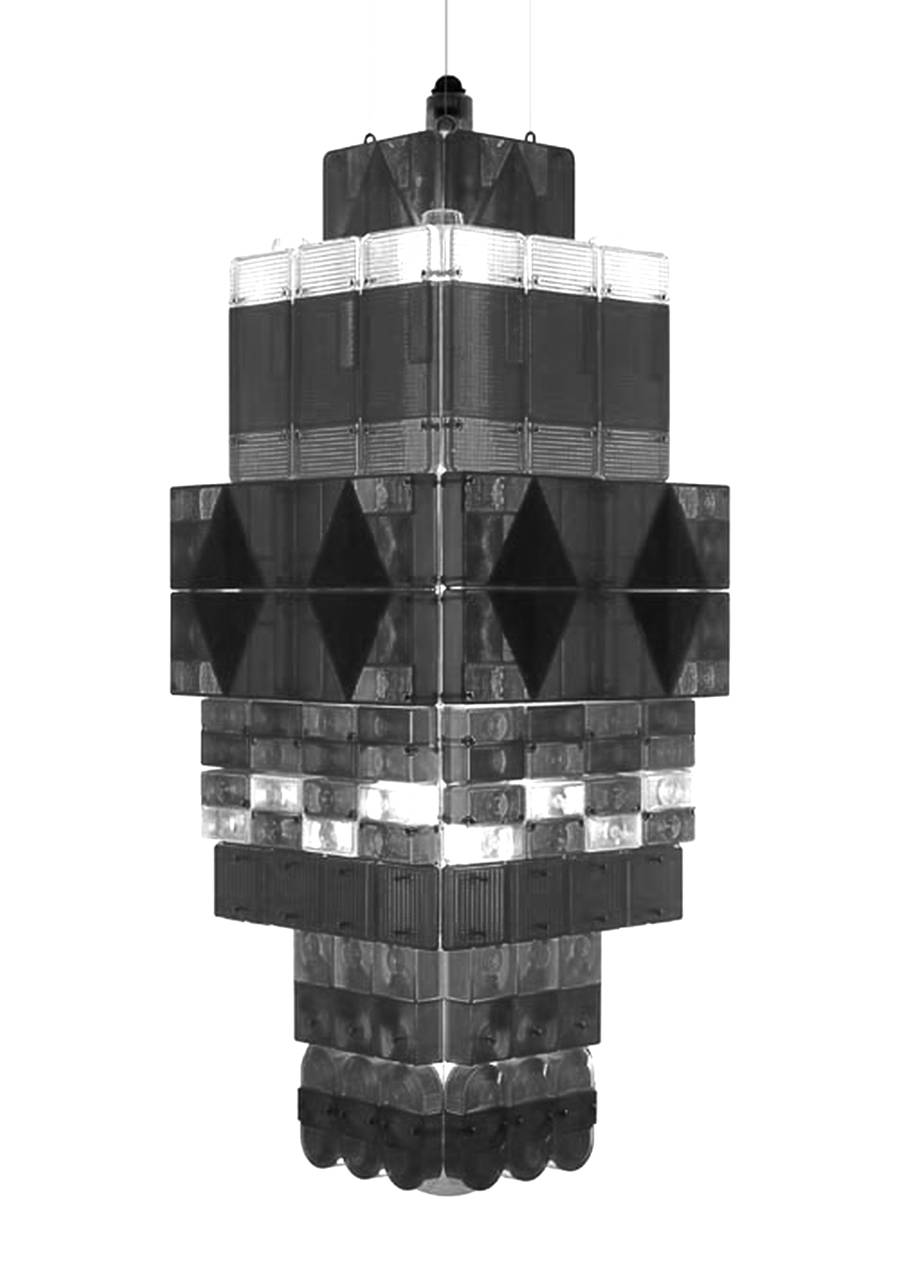

Another item taken from the same list is the Cassette Cabinet

(see Figure 2). In making something from what we have lost through

the advances of technology, this cabinet valorizes nostalgia:

37 Jean Baudrillard, For a Critique of the

Mixtapes have long been used to commemorate love (and

Political Economy of Sign (St. Louis:

Telos Press Publishing, 1981), 64-5.

heartbreak), season changes, irrational obsessions with a

38 “25 Innovative Re-Purposed Home

band, and life milestones. (It’s easier to turn 30 when it’s

Fittings Designs,” FreshBump,

to the soundtrack of Aretha Franklin.) Now that we’re in

http://www.freshbump.com/featured/

featured/25-innovative-re-purposed-

home-fittings-designs/ (accessed April

1, 2009).

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

69

the compact disc age, you’re stuck with cassette tapes filled

with dated music and emotions, but all’s not lost. Creative

Barn shows how tapes can serve a more valiant purpose

than collecting dust.39

The cabinet, designed by Patrick Schuur, was made by placing 918

cassette tapes on a wooden frame structured to create a spacious

storage area. It endows the once-useless mountain of garbage with

a new function. In addition, this monument of archaic cassettes

unearths and pays tribute to the distant memories, forgotten

moments, and absent people embedded in those memories.

One last example from the list is the mattress chair, Madam

Rubens, designed by Frank Willems (see Figure 3).40 In the design-

er’s description, “Madam Rubens is a plump but sophisticated lady

after an extreme makeover. She started her life as a mattress but

was thrown away after years of loyal service.”41 Recognizing that

mattresses cannot be recycled, the designer develops this solution,

guided largely by an environmentalist responsibility. The chair is

a combination of a disposed mattress and the legs of an antique

Figure 2

chair. For each chair, the mattress is folded in a different way and

Cassette Cabinet by Patrick Schuur (Photo by

Wouter Walmink).

combined with different chair legs to assure that Madam Rubens is

unique every time. The chair also is painted in a bright vivid color

of choice to complement its newish look. Thus, “Madam Rubens is

back in business as a fresh, hygienic, and exceptionally stylish tool.”42

If these old-fashioned table legs were not combined in such an

innovative manner with an already discarded mattress, they would

likely be thrown away to be replaced by brand-new minimalist ones

and would never be re-placed in the first place, at home. Moreover,

the mattress, which has never been put on display before, steps up

to the living room as an object of distinction. Any traces of outdated-

ness and mediocrity are erased and re-valued through a redefined

function and a chic appearance. In this case the style is rescued

from the past and its remnants, translated through the conduits of

disposal, are transformed into a new design language.

All these translations can be considered reincarnations or

rebirths, following Hetherington’s adaptation of the two-phased

burial practices in certain cultures that are introduced by Hertz to

the realm of inanimate objects. The first place of burial for the objects

can be “the bookcase, the recycle bin on a computer, the garage,

the potting shed, the fridge, the wardrobe, even the bin” in which

the objects are left for some time “while their uncertain value state

is addressed . . . before being removed into the representational

39 Ibid.

outside, where they undergo their second burial in the incinera-

40 Ibid.

tor, the landfill, or unfortunately sometimes just fly-tipped onto the

41 Frank Willems official webpage, http://

side of the road.”43 The interval between the two processes is of great

www.frankwillems.net/ (accessed

October 24, 2011).

42 Ibid.

43 Hetherington, “Secondhandedness,” 169.

70

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012