The Quiet Dissemination of

American Modernism: George

Sakier’s Designs

for American Radiator

Christine Taylor Klein

George Sakier was a versatile practitioner who worked as an interior

designer, painter, art director, engineer, and packaging designer. He

was also one of the original industrial designers in America. His

career path was as diverse as it was extensive, and his impact upon

the development of a modern design aesthetic pervaded not only in

the United States but also in Europe.

To understand Sakier’s ability to produce designs that have

become so pervasive in the American household, one must look to

his earlier career—a period of time that Fortune magazine called

his “trek from camouflage to bathtubs.”1 During this era, partic-

ularly in the 1930s, Sakier emerged as an arbiter of modernism and

as one of the first industrial designers. His bathroom and kitchen

fixture designs for the American Radiator Company reveal some of

the earliest embodiments of a uniquely American modernist style.

Through the market appeal and affordability of his industrially

designed products, Sakier quietly disseminated his modern aesthetic

throughout the country.

1 George Nelson, “Both Fish and Fowl,”

Fortune (February 1934), 40.

2 Sakier’s descendents believe that the

From Camouflage to Bathtubs

original family name may have been

Sakier’s father, Samuel, immigrated to Palestine as a member of

“Sirkin” and that Samuel, like many

the Bilu’im—a group of Zionists who fled Russia during the 1880s

Jewish immigrants of his time, may

to avoid the anti-Semitic “May Laws” of Tsar Alexander III.2 The

have changed his name when he

Bilu’im were trailblazing idealists that established an agrarian

moved to the United States.

3 For more on the BILU Movement,

cooperative society.3 Life in Palestine was fraught with disease and

see: Samuel Kurland and Hechalutz

drought, and by the turn of the century, Samuel left the farming

Organization of America, Biluim, Pioneers

experiment to settle in New York City, where he married and worked

of Zionist Colonization (New York: Pub.

as a paper and twine merchant.4 George was born the second of

for Hechalutz organization of America by

three children in December 1897. Although the family could not

Scopus publishing company, 1943).

4 “Samuel Sakier,” New York Times,

have been considered wealthy, each of the three children was given

January 4, 1934. This obituary claims

a high level of education. While both his siblings remained closely

that Samuel “settled in New York about

involved with their Jewish heritage (his older Brother Abraham

1900,” but given that George was born

was an ardent supporter of the Zionist movement and his younger

in 1897 and that George’s older brother

sister Helen was an active board member of a prominent Jewish

Abraham was also born in New York,

social agency), George took a dif erent path. His early exposure to

it is likely that Samuel arrived in the

US as early as 1894.

© 2011 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

81

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

influence the design discourse abroad. A decade later, when his

glassware designs for Fostoria first began receiving wide acclaim, he

would again influence the European modern aesthetic when “he

won the distinction of having his own designs for glass pirated

in Europe.”10

Sakier returned to New York around 1926. While in Europe,

he had gained experience as an assistant art director for French

Vogue, and he worked as art director for Modes and Manners and

Harper’s Bazaar until the end of the decade.11 By then, he had

also secured jobs as head designer at the American Radiator and

Sanitary Corporation and as a consultant designer for Fostoria

Glass Company. His service with both companies would last for

decades, and his work led him to wide acclaim in the new realm of

industrial design.

Fostoria, under whose employ Sakier made his most lauded

and recognizable work, was founded in 1887 in Fostoria, OH. The

location for the original factory was chosen “to take advantage of the

free natural gas offered [there] as an inducement to industrial users

with the money to set up a factory.”12 The company later moved to

West Virginia; Sakier would send his designs here for elaboration by

an in-house design team, and the products would be manufactured

and marketed to middle-class households all over the country.

Sakier was hired as part of Fostoria’s aggressive design overhaul—

an attempt to keep pace with the competition by modernizing its

wares.13 Under his direction, the company began to offer a broad

range of tableware, most of which evinced a combination of

neoclassical and modernist sensibilities. Fostoria prospered from

Sakier’s “simpler, friendlier” modernism, and its success inspired

other glassware companies to embrace the trend in the 1930s.14

As dynamic and innovative as Sakier’s designs were, they

often retained classical elements. Because he was designing for

the American middle-class consumer, even his more avant-garde

glass pieces tended to merely imply modernism rather than to fully

embody it. His geometric forms for footed stemware were often

accented with classical floral etching; candelabras with geometric

accents retained column-like fluting; and goblet stems were topped

10 Ibid.

with detailing similar to Roman capitals.

11 Piña,

Fostoria, 8.

12 Charles Lane Venable et al., China and

American Radiator and the Culture of the Bathroom

Glass in America, 1880-1980: From

Sakier’s full expression of modern, utilitarian purity and social

Tabletop to TV Tray (Dallas Museum

awareness is most evident and compelling in his work with the

of Art, 2000), 174.

American Radiator and Standard Sanitary Corporation. At first

13 Ibid.

14 “Notes on Glass Design,” Advertising

glance, plumbing may seem an unlikely catalyst for the prolif-

Arts (January 1933), 21. Quoted in

eration of modern design in America. However, plumbing and its

Kristina Wilson, Livable modernism:

accompanying fixtures are, in fact, rife with modernist implications.

interior decorating and design during the

Other parts of the house did not lend themselves as readily to such

Great Depression (Yale University Press

modern advances. “Designers and manufacturers,” Kristina Wilson

in association with the Yale University

Art Gallery, 2004).

has written, “found it more difficult to argue that a modernist sofa,

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

83

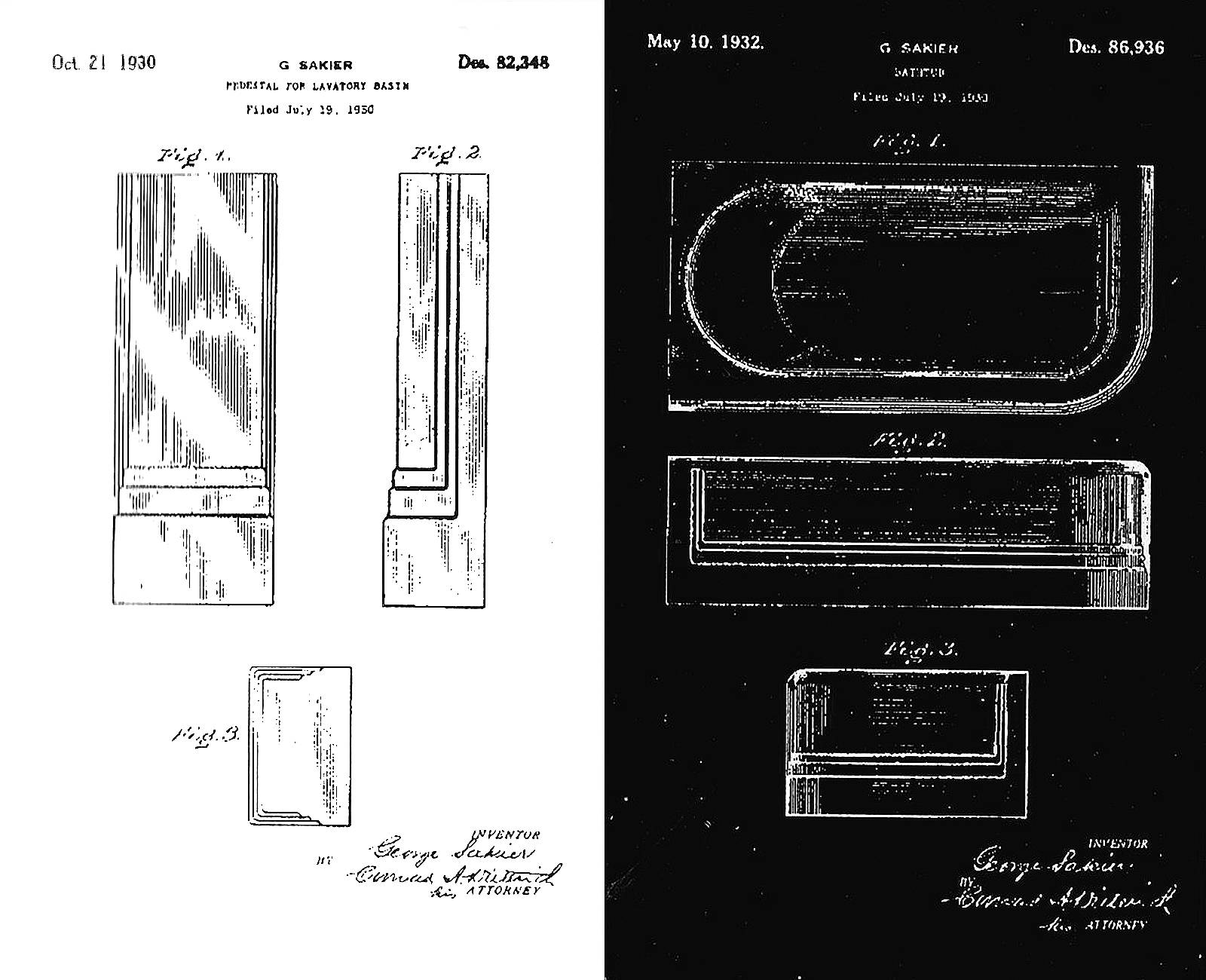

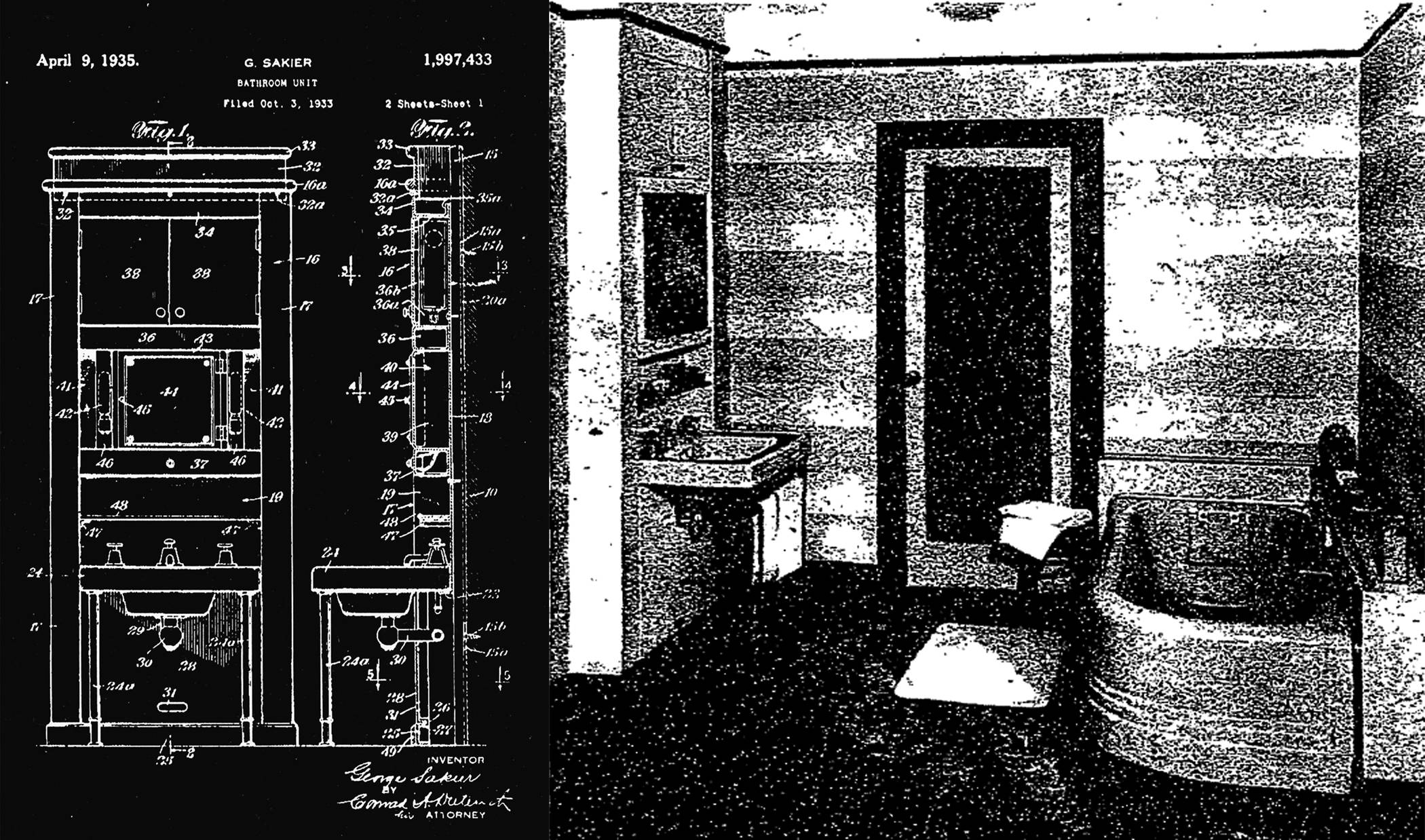

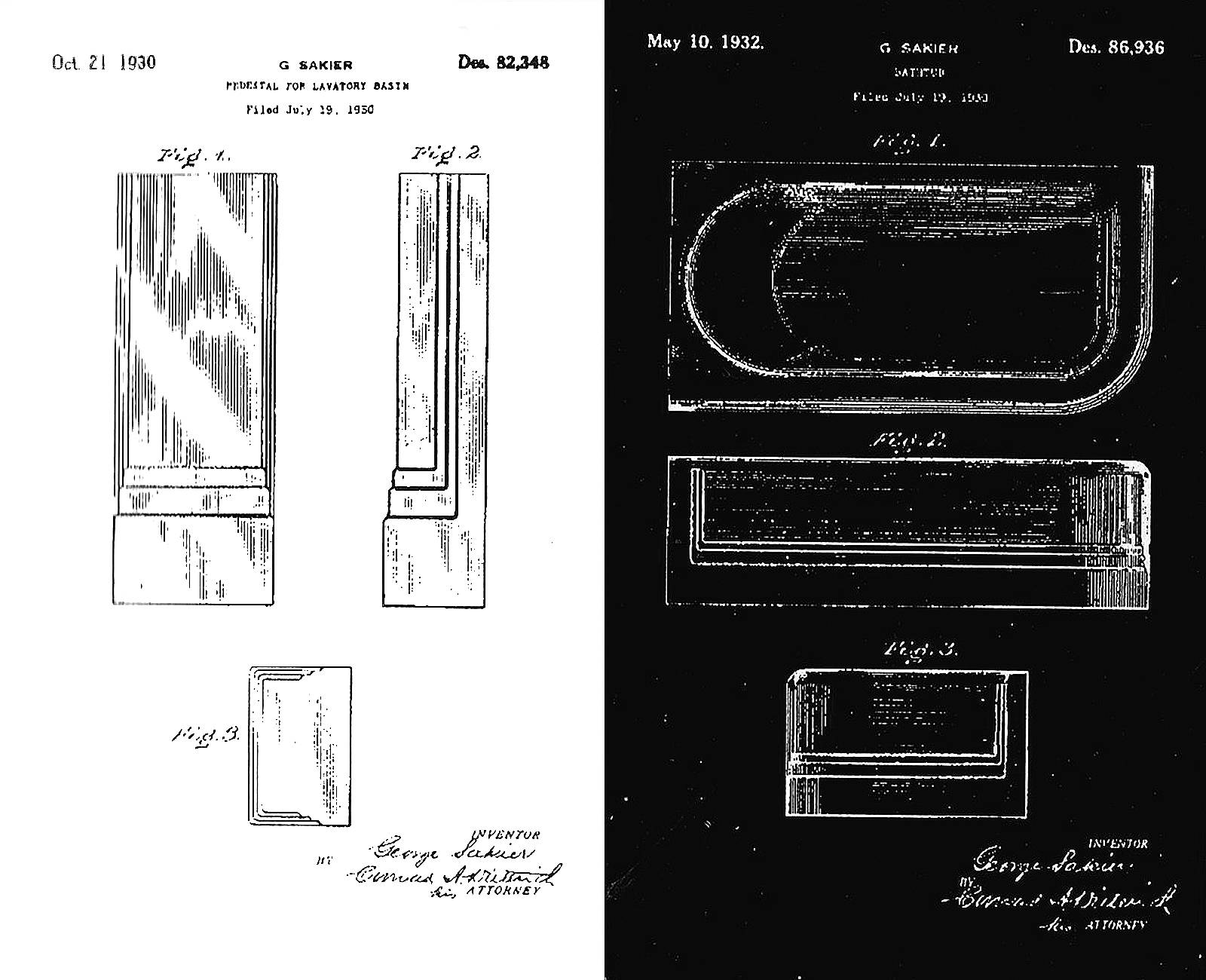

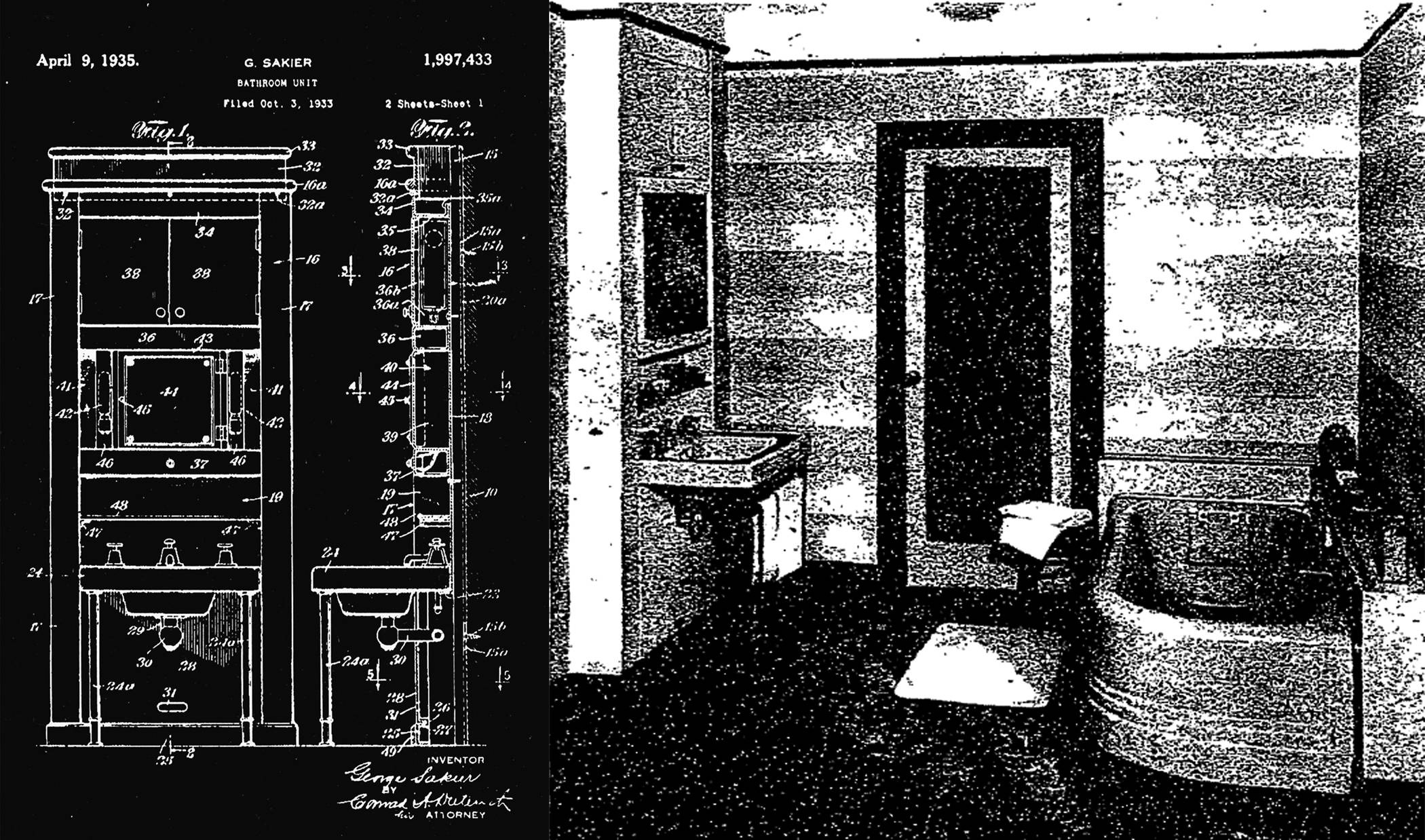

Figure 3

panels that Sakier designed for the company would ultimately

Patent drawings of the Neo-Classic line for

become his most modern and arguably most influential contri-

the Waldorf Astoria Hotel (lavatory basin

butions to industrial design.

pedestal, top; bathtub, bottom)

In his first years at American Radiator, his designs stayed

close to the typical neoclassical forms that drew great interest from

upper class consumers (see Figure 2). Critic Sheldon Cheney wrote

of his early works, “Sakier was creating exhibition ensembles as

luxurious as any of those advertised, for their ‘rich and Oriental

splendor,’ for their Greco-Roman ‘period’ authenticity, or for their

Spanish exoticism.”21 One bathroom design in particular, which

included oversized tubs and gold taps, was priced at an opulent

$7,000. Despite this application of ornament, Cheney, an ardent

modernist, conceded that Sakier’s design prowess shone through:

“[Sakier’s] work was always distinguished by a delicately perceptive

discrimination and a genuine originality in new material use.”22

All of this opulence would, of course, fall away in the

aftermath of the economic collapse of 1929, after which Sakier

would turn his attention toward a simpler and more astringent

aesthetic. Shortly after the market crash, construction began on the

new Waldorf-Astoria hotel in New York City. The architecture firm,

Schultz and Weaver, designed the remarkable building, then the

largest hotel in the world, with more than 2,000 guest rooms and 300

residential suites.23 Theo Arens, president of American Radiator and

Sakier’s boss, was determined to win the contract for the bathroom

installations, and he set Sakier to work designing an entirely new

line of fixtures for the hotel. The result was Sakier’s Neo-Classic line,

a misleading title given its strong lines and geometric shapes (see

Figure 3). In fact, he meant for the name to be interpreted literally; he

intended for the fixtures to become the “new classic” for bathrooms.

The design established an aesthetic based upon the utilitarian

function of the plumbing and machinery with which it operated.24

Schultz was pleased with the designs, and American Radiator won

out over Kohler, the hotel company’s previous supplier. The success

bolstered Sakier’s notoriety, propelling his designs into numerous

journals and magazines that praised the work as an embodiment

of the emerging machine aesthetic. Architect Raymond Hood,

21 Sheldon Cheney and Martha Smathers

who designed the American Radiator’s own high-rise building a

Candler Cheney, Art and the machine:

few years earlier, remarked that the fixtures had “an architectural

an account of industrial design in

character that blends them into the design of the room. They have

20th-century America (Acanthus Press,

the basic quality of good design,” he added, “of being straight-

1992), 78.

forward and simple.”25

22 Ibid.

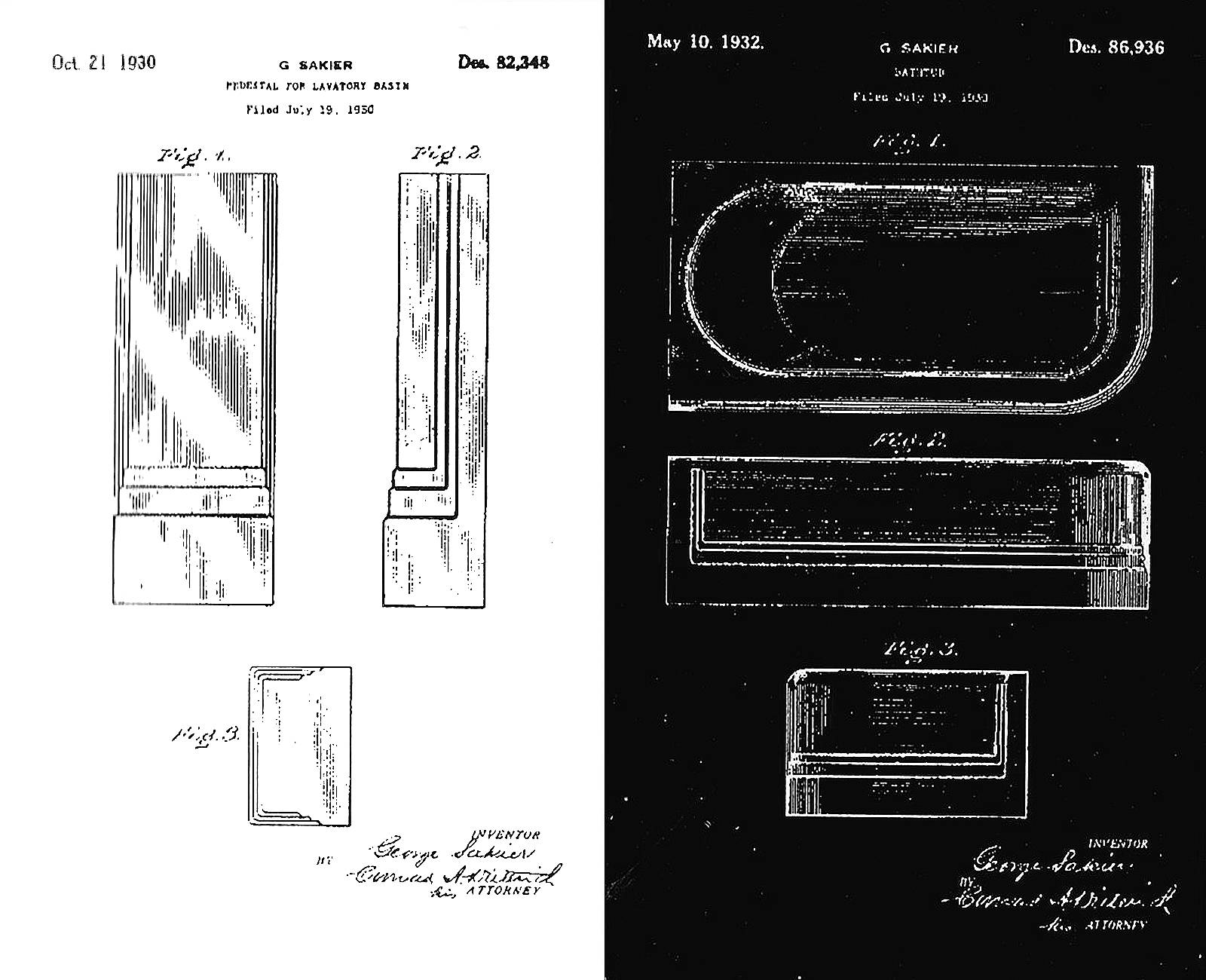

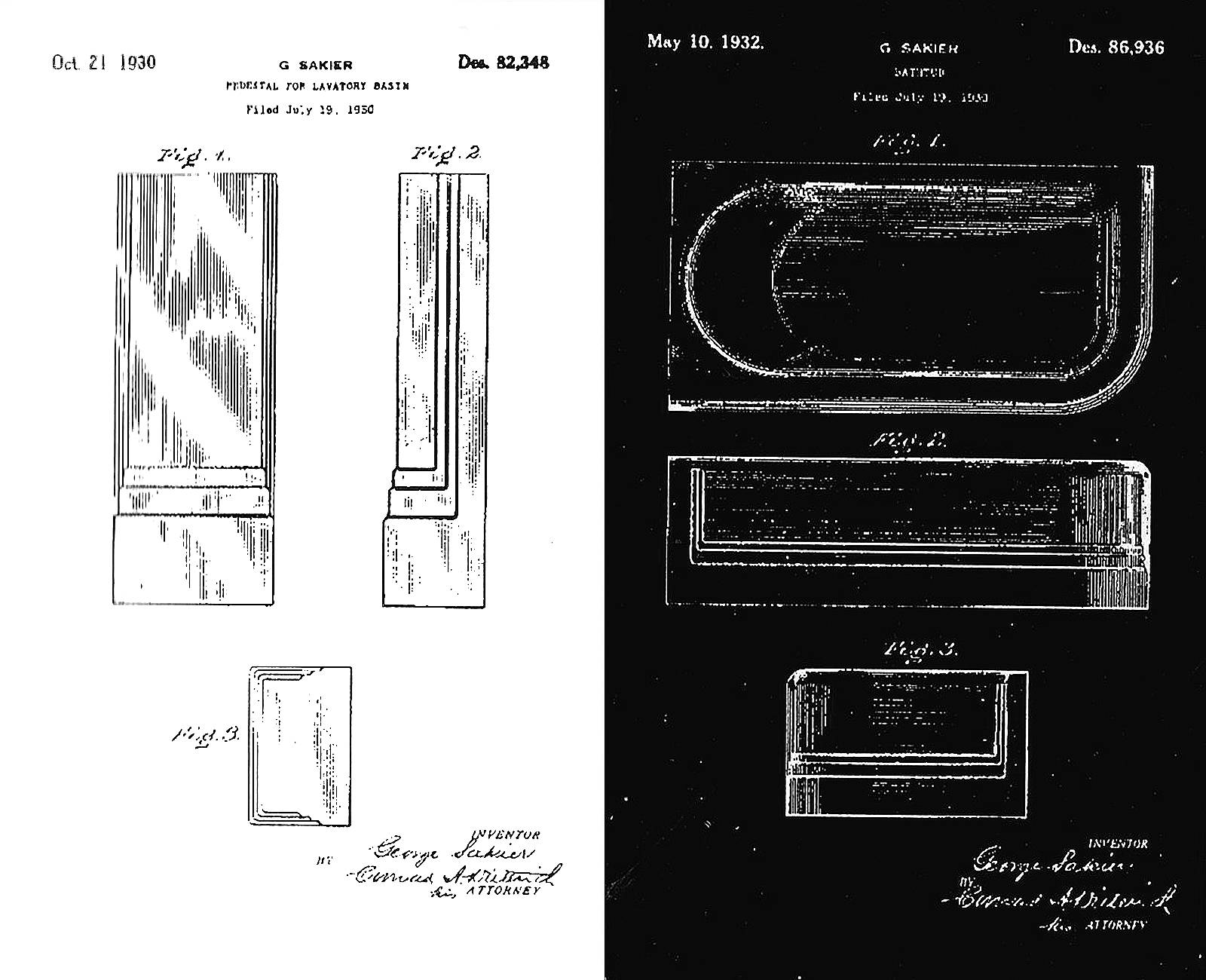

The Neo-Classic bathroom concept was exhibited in one of

23 Joseph J. Korom, The American

Skyscraper, 1850-1940: A Celebration of

the display rooms at The American Radiator and Standard Sanitary

Height (Branden Books, 2008), 423.

Corporation, and, in it, Sakier combined the modernized fixtures

24 Piña,

Fostoria, 109.

with elements of pared-down classicism to achieve maximum appeal

25 Raymond Hood quote originally posted

to consumers. Walter Rendel Storey, art critic for the New York Times,

in “What Others Say,” a promotional

described the fixtures as moving toward a “smart simplicity,” where

brochure for the Neo-Classical line.

Quoted in: Ibid., 113.

the “old-time fussiness of the ornamented bathroom has been

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

85

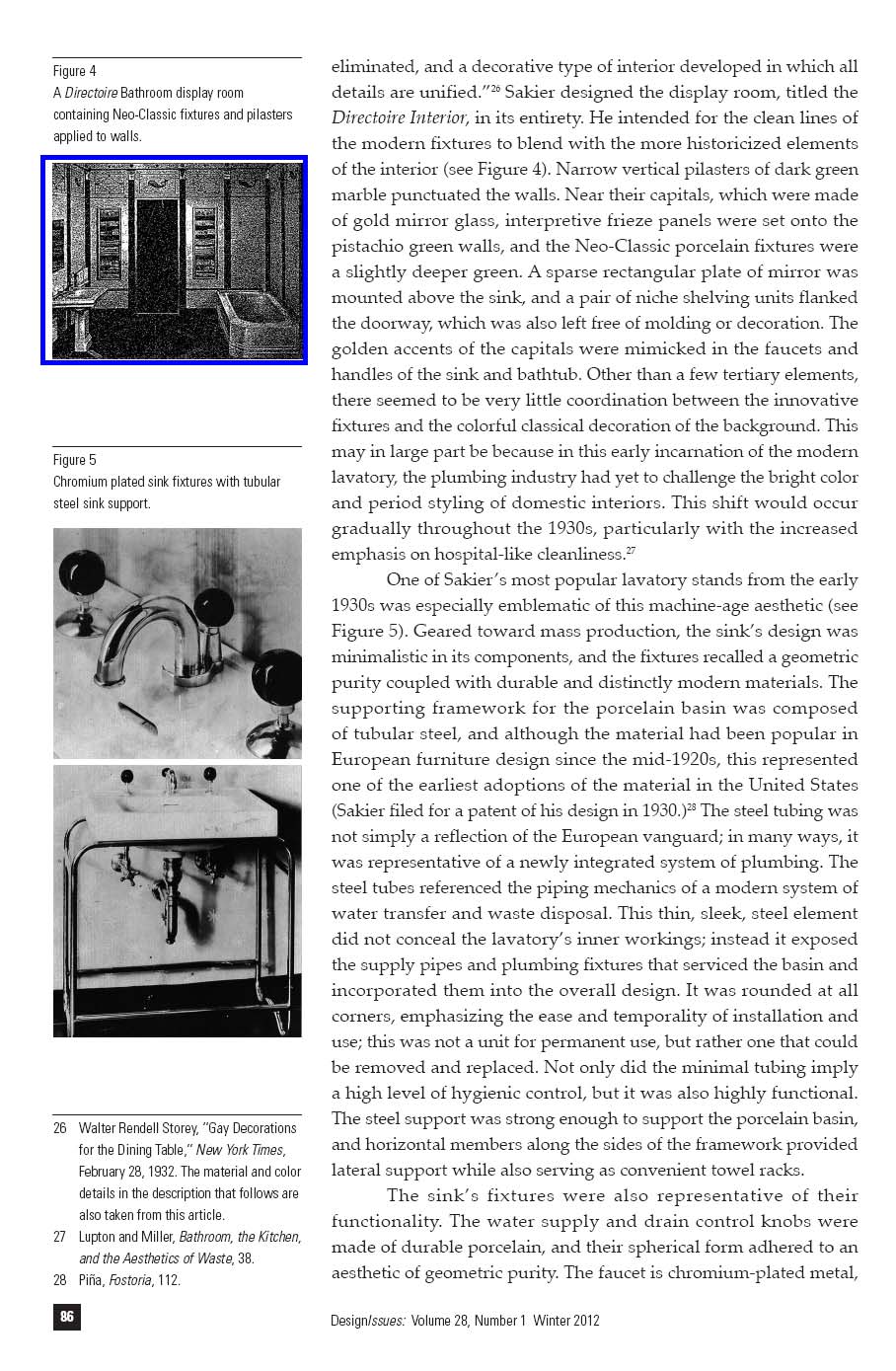

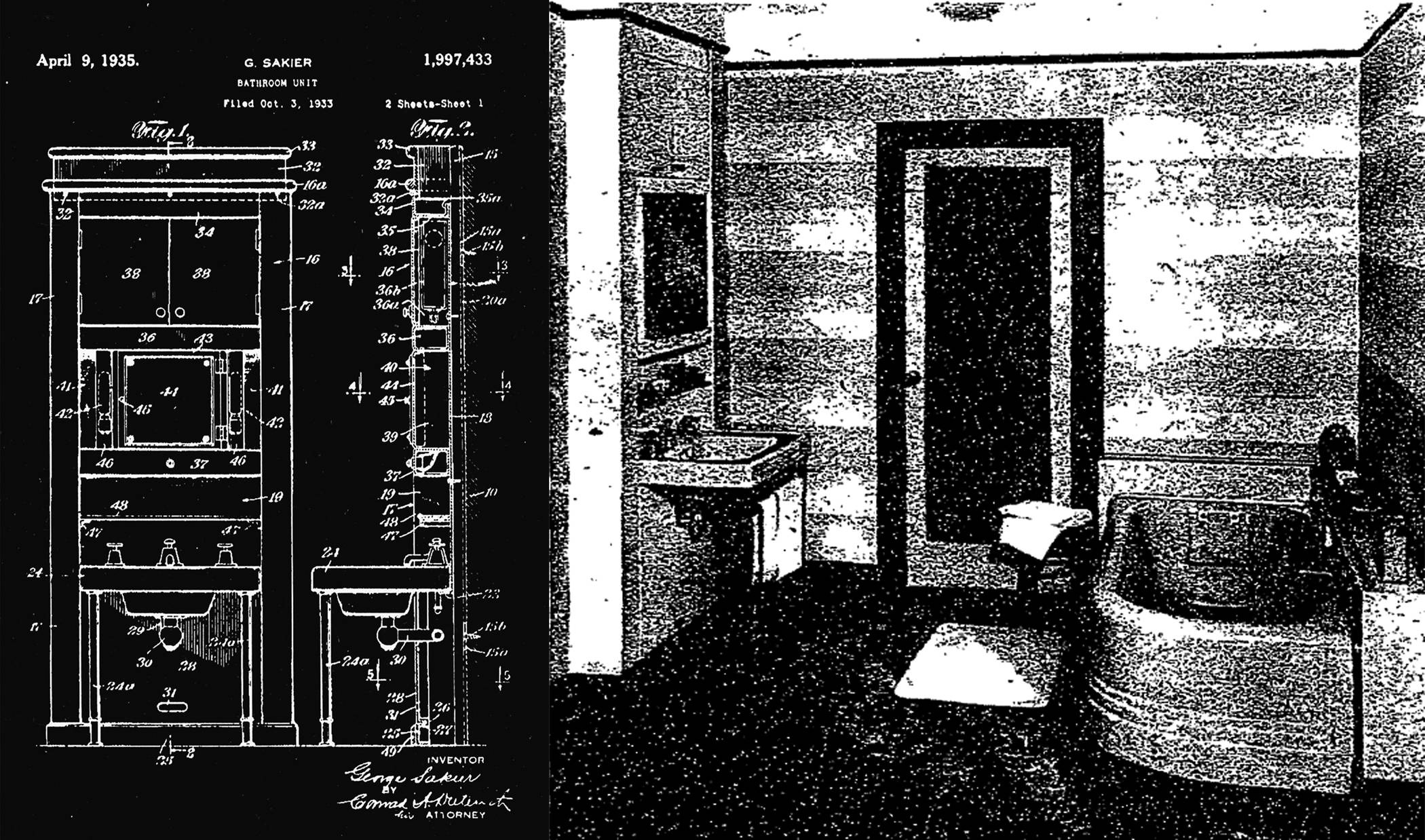

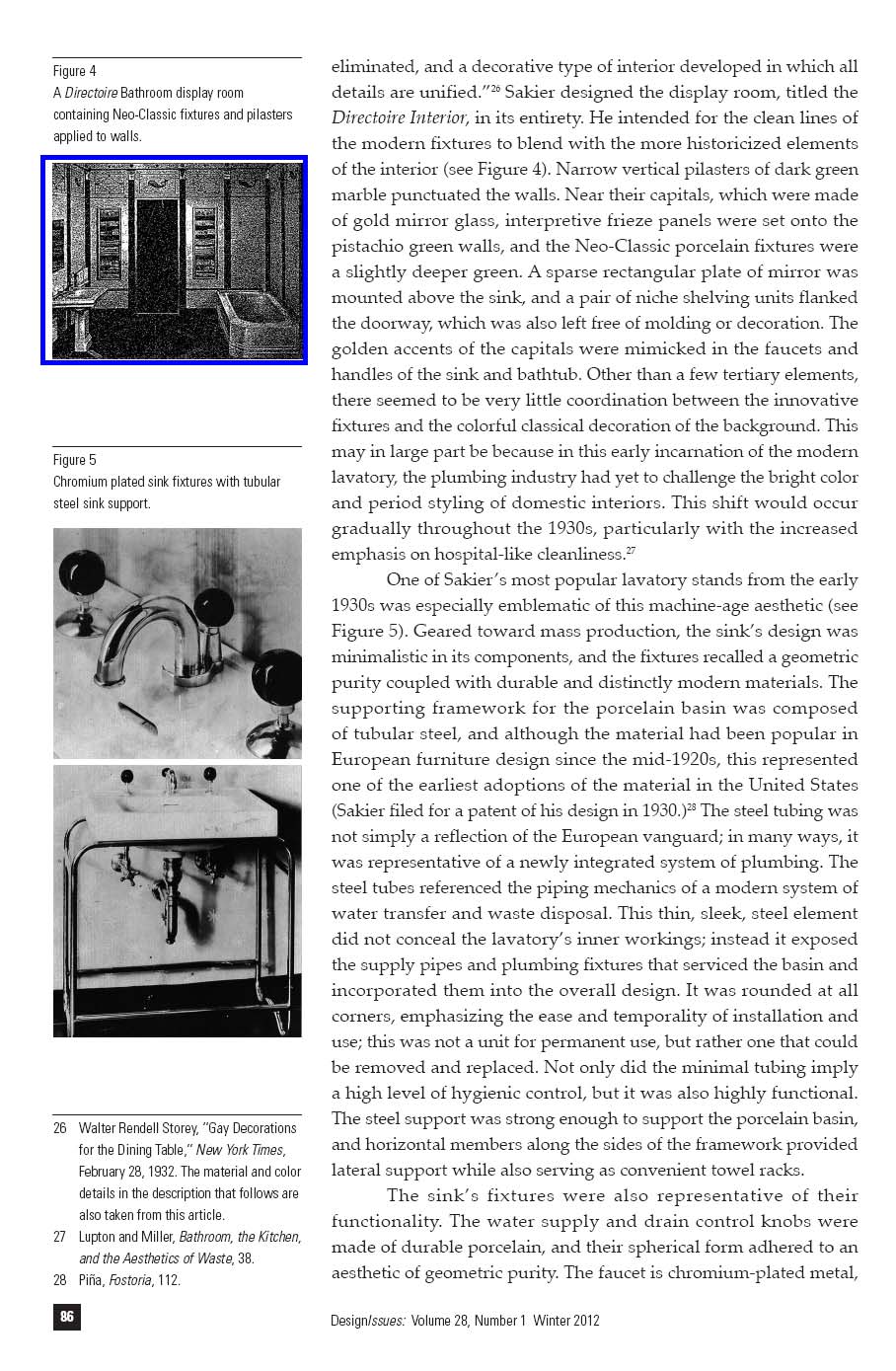

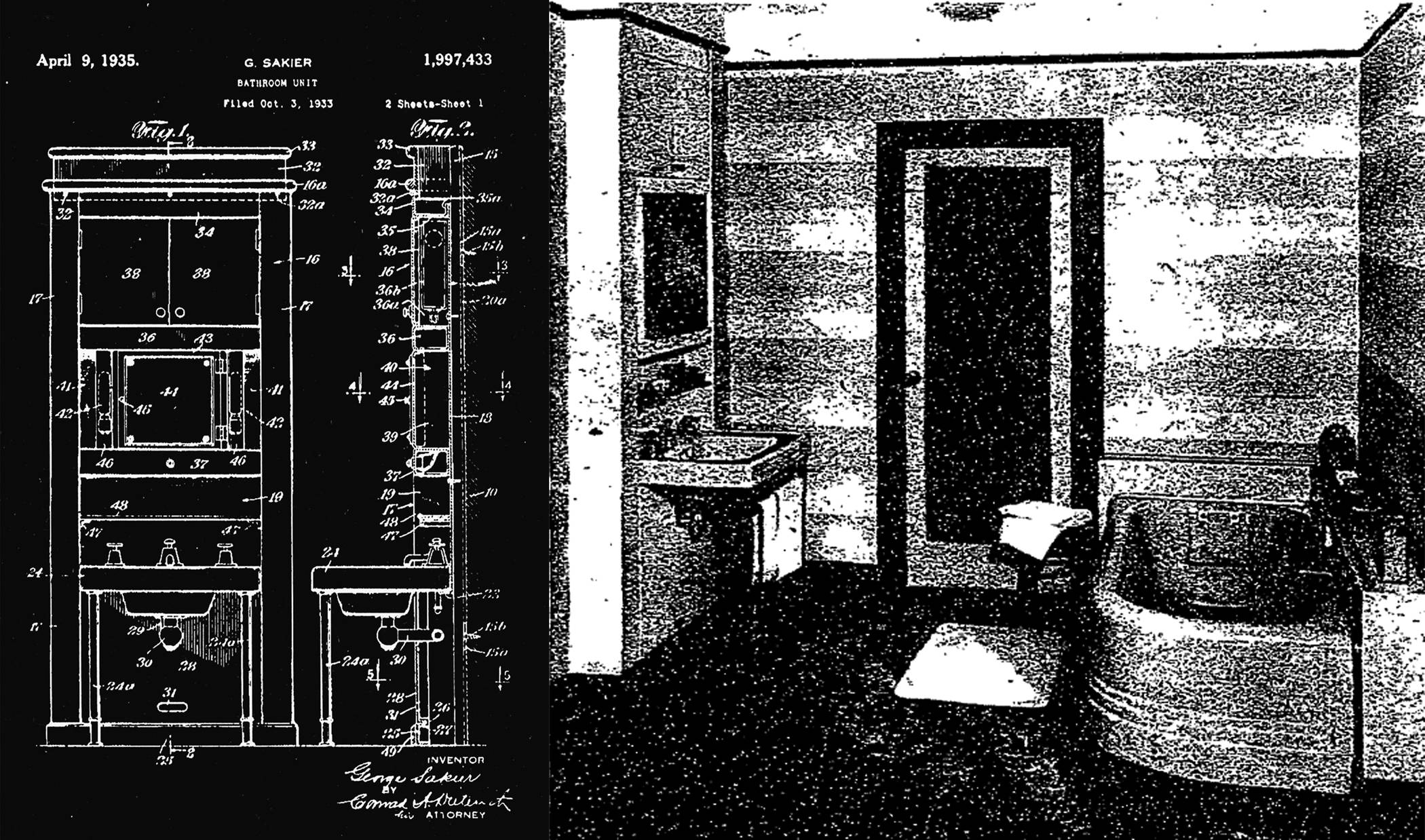

Figure 7

continuously added to production with little risk of outdating the

Top: patent drawing for the lavatory segment

previous lines, the tolerance for such rapid change, and subsequent

of the Arco Unit Panel System.

obsolescence, in the bathroom was considerably lower. Because of

Bottom: bathtub and lavatory units (shown in

the permanence of the fixtures and the organization of the laborers,

sheet metal)

the bathroom and plumbing industry was generally slower to

respond to new technologies. Aside from its inherent reluctance to

innovation, the plumbing fixture industry was also facing a growing

number of charges of an even greater economic and social nature.

George Nelson, in a 1934 piece for Fortune on the new vocation of

industrial design, cited this social neglect as leading to the “basic

indictment of the reactionary building industry which, in an

industrial capitalistic country, is technologically unable to build

houses cheap enough to house two-thirds of the people above a

minimal standard of decency.”33 An article in Architectural Record

pointed out that, despite the relative achievements of American

plumbing, a 1934 study of 64 typical cities revealed that “5% of all

dwellings had no running water, 13.5% had no private indoor water

closets, 20.2% had neither bathtubs nor showers.”34

Sakier answered this social charge with his design for the first

prefabricated bathroom, the Arco Unit Panel System, released in 1933

for the Accessories Company, a division of American Radiator (see

Figure 7).35 Cheney called it Sakier’s “machine for cleanliness”—the

bathroom’s response to Le Corbusier’s visualization of the home

as a “machine à habiter.”36 The system consisted of three separate

components—a washbasin, bathtub, and toilet—each containing

all the necessary fixtures and accessories in an adjustable metal

wall section for easy installation in new construction or joined to

existing plumbing for renovation work. The three main components,

along with additional paneling for the flooring and wal s, could be

interlocked to create a single unified system, or each part could be

used separately, depending on need and budget. The lavatory unit,

by far the most complex and inclusive, contained a porcelain bowl

with tubular metal legs and chromium-finished faucet components.

The sink element was attached to a wall panel six to eight inches

deep—deep enough to conceal the plumbing pipes and to avoid

disturbing the building wall. The panel included shelving and a

33 Nelson, “Both Fish and Fowl,” 97.

34 “Technical News and Research: A

mirrored medicine closet, bordered by lighting that conveniently

Prefabricated Bathroom” Architectural

plugged into the nearest wall socket. The panel was made of two

Record, (January 1937), 39.

vertically telescoping pieces to accommodate rooms of various

35 Note that Architectural Record in

heights, and the sink legs easily adjusted to account for uneven

1936 and 1937 consistently refered to

floors.37 The toilet component held the tank within the wall unit

these panels as “Arcode Sectionals.”

to remain accessible for quick repairs and, once again, to avoid any

Elsewhere, the systems are referred

to as Arco.

pipe installation within the building’s walls. An available option in

36 Cheney,

Art and the machine, 79.

this unit was a convector radiator, capable of heating an 8’ x 10’

37 Walter Rendell Storey, “Ease and Style

room, particularly in the area of the toilet.38 And, of course, the

in Outdoor Furniture,” New York Times,

colors and finishes of each component were customizable to suit the

June 18, 1933.

consumer’s taste. The system was a revolutionary contribution to the

38 “Technical News and Research: A

Prefabricated Bathroom,” 46.

88

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

development of prefabrication and industrial design in America. Its

high functionality and technical beauty earned the Arco Panel Unit

System a position in the influential Machine Art exhibition at New

York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1934.39

The entire system was designed to optimize comfort in use

and convenience in installation, while also imparting a modernist

look. More importantly, it was intended to be readily affordable

and widely applicable. The same year as the MoMA exhibit, it was

reported that 133 of the units were being installed in an apartment

building in Washington, DC, and 400 more were slated for instal-

lation in another building.40 Within a few years, the Arco Units were

installed in thousands of homes and apartments.41 The immediate

interest in the concept seemed to validate Sakier’s social initiative

and design ideal. However, the project never reached the level of

commercial success that his other lines with American Radiator

enjoyed. Like so many other attempts to market prefabricated

components in the 1930s and 1940s, including several later ef orts

by Buckminster Fuller, the unit was never adopted as a prototype.

Perhaps consumer interest waned when presented with such a

rigidly modernist system; perhaps the consumer could not reconcile

the notion of adaptable bathroom components with preconceptions

of the architectural fixedness of previous components. Most likely

to blame were the plumbers and contractors who failed to evolve

in response to the new technology. American architect Alexander

Kira reflected on the stubbornness within the “structuring of the

plumbing industry, which has followed the pattern peculiar to the

home-building industry: field erection and assembly of thousands

of independently produced and often unrelated items.”42

Despite these problems, Sakier continued to investigate

prefabrication as a mode of production and installation with the

introduction of the “packaged kitchen” assembly for the Accessories

Company in 1936. The kitchen panels were intended to complement

those of the bathroom system and implemented many of the same

design ideals. Steel wall sections, each of which were capable of

sustaining a bearing load of 7,000 pounds, were assembled and

framed into the house, and the cabinets and equipment were

mounted on this system.43 The system was modular, offering 15, 20,

39 For more information on the exhibit,

and 35-inch segments to allow for flexibility in arrangement and to

see Machine Art: March 6 to April 30,

accommodate different types of layouts. For a large kitchen with a

1934, Museum of Modern Art, New

pantry, the retail price was around $500, but the smaller, straight-line

York (New York: Museum of Modern

assemblies could run as low as $275. The units were broken down

Art, 1969).

40 Nelson, “Both Fish and Fowl,” 98.

into different construction types to allow for the various levels of

41 Cheney,

Art and the machine, 79.

budgeting. Different assemblies were offered for houses in several

42 Alexander Kira, The Bathroom (Viking

different price ranges: $15,000 and above, $8,000 to $15,000, and

Press, 1976), 9.

less than $8,000. Sakier designed the kitchen system to be highly

43 This description is paraphrased from

functional, while also promoting modern hygiene and efficiency.

“Technical News and Research:

Integrated Kitchens,” Architectural

Record (October 1936).

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012

89

In 1936, he wrote an article for House and Garden intended to

appeal to female consumers, who were the primary market for such

fixtures. He equated the chore of cooking with a type of artistry and

invited his female readers to “imagine a breadboard that lets down

at the touch of a finger,” or “a ‘kitchen dashboard’ with sockets and

switches for electric appliances.”44 There was a designated area for a

paper towel roll right next to the sink faucets, “where, of course, it

should be.”45 If his prefabricated bathroom panels were “machines

for cleanliness,” then his kitchen systems were machines for cooking,

cleaning, storing, and household management. Sakier was able to

successfully combine modern modes of design and assembly with

the traditional methods of household engineering promoted a

decade earlier by Christine Frederick, who argued that each aspect

of the kitchen should be composed to minimize labor and maximize

comfort and ease of use.46

A Modest Legacy of Modernism

With each of these designs, Sakier sought to inject the new ideals

of modernism into the accessories of domestic life. As an artist, his

work for American Radiator seemed an odd fit—even to him—

although ultimately he found it a satisfying situation: “At dinner,”

he once wrote, “when my partner feels it is about time to ask what

I do, I general y, albeit I have more romantic wares to of er, answer

that I design bathtubs. The response is electric, earnest, and most

gratifying. I am now sure of her complete attention for at least three

courses… I become a social asset.”47 Although painting remained

his passion, Sakier relished the notion that his designs had spread

so broadly across the country, imparting his ideals of functionality

and efficiency into innumerable homes.

Acknowledgements

This article is the result of Professor Christopher Long’s seminar

course on Modern American Design at the University of Texas at

Austin. I owe a debt of thanks to Professor Long for his guidance

and encouragement. Thanks also to Susan Blumberg, Sakier’s

grandniece, Martha González Palacios, head librarian of the

Architecture and Planning Library at the University of Texas at

Austin, and Christian Klein, professional designer and intellectual

buttress.

44 George Sakier, “Her Kitchen,”House

and Garden 70 (October 1936), 142.

45 Ibid.

46 Christine Frederick, Household

Engineering: Scientific Management

in the Home (American School of

Home Economics, 1920).

47 George Sakier, “Hot and Cold,”

photocopy of undated article in

George Sakier Foundation archives.

Quoted in Piña, Fostoria.

90

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 1 Winter 2012