Knowing Their Space: Signs of

Jim Crow in the Segregated South

Elizabeth Guffey

Figure 1

Peter Sekaer, Movie Theater, Anniston,

Alabama, 1935-6. Courtesy of Peter

Sekaer estate.

“They had black, well it was “colored” back then, on one side and “white”

on the other, and we had our place on the bus, we had our water fountains

for coloreds and our bathrooms for coloreds . . . we figured that’s just the

way it’s supposed to be.”1

”Jim Crow” was a character portrayed by the black-face minstrel,

Thomas “Daddy” Rice, whose stage performances in the 1830s and

1840s typified many whites’ view of African-Americans through-

out the nineteenth century. Jim Crow segregationist signs, believed

to have been named for this character, are emblematic of south-

1 “Oral History Interview with Sheila

ern white leaders’ unrelenting effort to enforce African-American

Florence, January 20, 2001, Interview

subservience after slavery was outlawed.2 Spread across a vast

K-0544. Southern Oral History Program

region of the southern United States, these visual communications

Collection (#4007),” http://docsouth.unc.

systems confirmed the re-marginalization of African Americans in

edu/sohp/K0544/excerpts/excerpt_1126.

html (accessed September 01, 2008).

the aftermath of the Civil War and subsequent Reconstruction. Four

2 Robert R. Weyeneth, “Architecture of

generations of Southern blacks endured Jim Crow laws; only now,

Racial Segregation: The Challenges of

some 50 years after the height of the Civil Rights Movement, are

Preserving the Problematical Past,”The

scholars beginning to examine the ubiquitous signage that kept this

Public Historian 27 (Fall 2005): 11-44.

system of oppression in place.3 Although these Jim Crow signs have

3 Elizabeth Abel, Signs of the Times,

(Berkeley: University of California, 2010).

© 2012 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 2 Spring 2012

41

begun to be considered in spatial and semiotic terms, an impor-

tant alternative is to view them through the lens of design history.

Design historians have paid scant attention to Jim Crow signs as

artifacts, or as parts of processes or systems, but doing so illumi-

nates important aspects of the signs’ function and appearance,

examining how their style made them meaningful and authori-

tative. Even more important, when recognized as a feature of

communication design history, they remind us how often design is

used to enforce social regulation (see Figure 1).

To many blacks and whites living in the South, racial

stratification might have seemed “just the way it’s supposed to

be.” However, segregation and the signs that expressed it were

consciously legislated and designed. Moreover, just as they were

rarely considered by contemporary scholars and social critics

of the time, they are rarely examined by design historians today.

Nevertheless, these signs can also be read as an early and practical

example of wayfinding. These signs confirm how design—whether

of individual letterforms and or of complete signage systems—

must always be involved in critical discourses of social, economic,

and political power.

A Missing Design Legacy?

Jim Crow signs existed in the United States for nearly a century,

but the signs themselves have utterly disappeared from public

spaces. Even documentation of their once ubiquitous presence is

rare. After scouring private and public archives, scholar Elizabeth

Abel has uncovered little more than 100 photographs of these

signs.4 As Abel suggests, both the signs and the photos of them

might have been destroyed after Jim Crow laws were overturned;

most likely many of them were simply thrown away.

One likelihood is that the very ubiquity of such signage

has worked against our remembering it today. As Abel notes, Jim

Crow signs were considered “about as worthy of documentation

as telephone poles or traffic signs, and typical y appear, if at all,

only in the background of the places or events whose documenta-

tion was the primary goal.”5 Despite their once pervasive presence

in the American South, the little visual documentation left has led

design historians to overlook this aspect of visual communications

history. Nevertheless, Jim Crow signs il ustrate how maps, signs,

and other wayfinding devices, while providing critical informa-

tion, also can pervade our consciousness and subconsciousness

and subtly shape our choice of action.

Understanding Wayfinding

An outgrowth of urbanism and mass transportation, large-scale

wayfinding systems have emerged in the postwar period. Architect

Kevin Lynch’s 1960 publication The Image of the City introduced

4 Ibid., 107.

5 Ibid.

wayfinding as a distinct field of study by analyzing how people

42

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 2 Spring 2012

perceive, remember, think, speak, and solve problems while trying

to navigate urban spaces. Building on Lynch’s seminal work and

noting that wayfinding is anything but static, designer Paul Arthur

and architect and environmental psychologist Romedi Passini

argue that wayfinding is more than generating a static mental map

of a spatial situation: it is a form of spatial problem-solving based

on understanding and comprehension. It involves knowing where

you are in a building or an environment, identifying where your

desired location is, and understanding how to get there. Successful

wayfinding systems do not rely on architecture or barriers alone;

instead, they require the consistent identification and marking of

Figure 2

space. Often seen as essential to the design process, wayfinding

Esther Bubley, Anonymous, A Greyhound bus

today is applied to relatively small-scale projects, including rural

trip from Louisville, Kentucky, to Memphis,

hospitals in Nebraska, as well as to the planning of entire cities

Tennessee, and the terminals. Sign at bus

station. Rome, Georgia, 1943. U.S. Farm

under construction in the Gulf states. Above all, wayfinding is

Security Administration/Office of War

conceived as a form of communications that guides the movement

Information, Prints & Photographs Division,

of large numbers of people, allowing them to perceive, engage and

Library of Congress, LC-USW3- 037939-E.

navigate through physical and conceptual space.6

Unfortunately in design studies today, wayfinding is a

practice-driven field. Designers generally resort to a positivist

conception of wayfinding that aims to protect wayfarers from

the uncertainty that can occur when, in the words of geographer

Reginald Gol edge, “even momentary disorientation and lack of

recognition of immediate surrounds” causes them to feel lost.7

Passini, for instance, emphasizes how “wayfinding difficulties and

6 With the 1960 publication of The Image

disorientation are highly stressful even in benign cases when the

of the City, (Boston: MIT Press, 1960)

user of a setting is merely confused or delayed. Total disorienta-

architect Kevin Lynch highlighted how

tion and the sensation of being lost can be a frightening experience

individuals perceive, remember, think

and lead to quite severe emotional reactions including anxiety and

of, and describe public space. Based

insecurity…“8

on “Perceptual Form of the City,”

a study funded by the Rockefel er

Because wayfinding is deeply infused with an ardent posi-

Foundation and conducted at MIT with

tivism, linking the field with something so loathsome as racial

designer György Kepes from 1954 to

segregation may seem unwarranted or even quixotic. Wayfinding

1959, Lynch’s analysis of how people

today is intended to help, not hinder, an individual’s passage.

perceive, remember, think, speak, and

Arthur and Passini admit that “it is unlikely that a person will actu-

solve problems while trying to navigate

ally die from the stress of getting lost.” With the result that “we

urban spaces introduced wayfinding as

a distinct field of study.

have tended to downgrade this problem as being relatively unim-

7 Reginald G. Golledge, Wayfinding

portant.”9 In this study, I explore Jim Crow signage within the

Behavior: Cognitive Mapping and Other

larger design tradition. As theorists like Kevin Lynch and practitio-

Spatial Processes (Baltimore: John

ners like Otl Aicher were developing the beginnings of wayfinding

Hopkins University Press,1998), 5.

thought and systems, this earlier, if only partial, system of wayfind-

8 Romedi Passini, “Wayfinding Research

and Design,” in Jorge Frascara, Design

ing was being dismantled. Although the Jim Crow system predates

and the Social Sciences: Making

the more modern ideas of wayfinding, its function and execution

Connections,” (New York: Taylor and

are best understood as an early example of the spatial decision

Frances Press, 2002), 97.

making that wayfinding now represents (see Figure 2). Counter to

9 Romedi Passini and Paul Arthur,

Arthur and Passini’s view, however, segregation signs were, in fact,

Wayfinding: People, Signs, and

part of a larger racial caste system that made them a life or death

Architecture (New York: McGraw Hill,

1992), 6.

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 2 Spring 2012

43

issue. In the larger design context, segregation signage involves a

complex negotiation—both guiding individuals and molding their

behavior. Jim Crow signs clearly inscribe space, but what “way”

did these signs help people to find?

Space and Jim Crow Geography

As the relatively recent development of critical geography has

pushed geographers from studying landscapes and objects to

examining the space around them, historians have begun to

re-examine notions of segregation in the South. French sociologist

and philosopher Henri Lefebvre studied the “production of space”

as a largely theoretical construct.10 A Marxian philosopher, Lefebvre

argued that space can be social as well as geographical, and concep-

tions of space have a cultural and highly changeable basis. Insisting

that conceptions of space can deny individuals’ and communities’

“rights to space,” Lefebvre argued for greater understanding of the

struggles over and meanings of space. Building on these insights,

geographers have begun in the past 30 years to urge an examina-

tion of lived experience and the spaces that shape ordinary life.11

In that light, scholars explore the evolution and effect of Southern

segregation, noting that it reflects a complex constellation of issues

revolving around racialized space. For example, Lawrence Levine

suggests that slaves created a metaphorical separate space for their

own cultural forms, and that “slave music, slave religion, slave

folk beliefs—the entire sacred world of the black slaves—created

the necessary space between the slaves and their owners and were

the means of preventing legal slavery from becoming spiritual slav-

ery.”12 Meanwhile, in Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in

10 Indeed, Lefebvre introduces the notion

the South, historian Elizabeth Grace Hale argues that segregation-

of the production of space as something

ists in the twentieth century tried to establish not metaphorical

that “sounds bizarre, so great is the say

but literal black and white spaces that shaped patterns of living;

still held by the idea that empty space

is prior to whatever ends up filling it.”

she sees this landscape of territorialism and exclusion as both

Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space

driven and challenged by capitalist expansion in the South.13 For

(Oxford: Blackwell, 1991), 15.

Hale, “consumer culture created spaces—from railroads to general

11 This notion is linked to the German

stores and gas stations to the restaurants, movie theaters, and

phenomenological concept that geog-

more specialized stores of the growing towns—in which African

raphers have adopted of lebenswelt

or “lifeworld.” See J. Eyles, Sense of

Americans could challenge segregation. . . The difficulty of racial

Place (Warrington: Silverbrook Press,

control over the new spaces of consumption, in turn, provoked an

1985) and David Seamon, Geography

even more formulaic insistence on ‘For Colored’ and ’For White.’”14

of the Lifeworld: Movement, Rest, and

More recently, Elizabeth Abel provides a rich discussion of

Encounter (New York: St. Martin’s Press,

segregation, examining for instance the “science” of racial differ-

1979).

ence; in doing so, she considers the Jim Crow signs and the rare

12 Lawrence Levine, Black Culture and

Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk

WPA photographs that documented them as part of a semiotic

Thought from Slavery to Freedom (New

system. Looking at archival photographs of the signs today, she

York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 80.

argues, “we can chart the changing intersections among a specific

13 Grace Elizabeth Hale, Making Whiteness:

disposition of racial terms, the angles of vision they afford, the

The Culture of Segregation in the South,

photographic practices they enlist, the modes of resistance they

1890-1940 (New York: Vintage, 1999).

14 Ibid., 125.

44

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 2 Spring 2012

galvanize, and the critical perspectives they engage.” While she

focuses primarily on photography’s “ostensibly neutral practice

of observation,” Abel strives to reveal “a more charged interac-

tion with the cinematic camera, [as well as] a political y engaged

photojournalism” that documents this signage. By concentrat-

ing on photographs of Jim Crow signs rather than on the signs

themselves, Abel’s analysis engages the process and purpose of

photography; in so doing, she includes signage as one part of a

larger “mode of expression” made by “public officials and private

individuals, professional signmakers and amateur scribblers.”

She concludes that the photos of Jim Crow signs are a form of

“American graffiti.”15 Meanwhile, the signs themselves, far from

being a subversive form of public communication casual y scrib-

bled on abandoned wal s, represent a particular aspect of a design

tradition—one that not only involved intentional design, but

that carried a power and intent that can be linked to larger legal

systems (see Figure 1).

Jim Crow Law

Jim Crow laws were relatively rare before 1895, when the African-

American Homer Plessy lost his Supreme Court suit against the

State of Louisiana. Plessy’s lawsuit was intended to bring atten-

tion to an 1890 Louisiana law that dictated segregated transport;

ironically, the authority and publicity of the Supreme Court judg-

ment helped concretize the concept of “separate but equal” spaces,

providing firm legal footing for institutionalized racism in the

United States. Southern segregation signs reflect a pervasive patch-

work of local and state laws that formed a racialized order through-

out the region.

In the decade following the Plessy ruling, state and munic-

ipal legislators throughout the South passed a spate of new laws

that regulated daily life;16 these mandates were so pervasive that the

phrase “Jim Crow law” first appeared in the Dictionary of American

English in 1904.17 Many of the most prominent segregation laws

15 See Abel’s first chapter, “American

dictated separate spaces on public transportation, including trains,

Graffiti: The Social Life of Jim Crow

streetcars, and trolleys. By 1909, 14 state legislatures enacted laws in

Signs,” 36.

16 For more on Jim Crow laws at the state

which passengers were assigned separate coaches, compartments,

level, see Pauli Murray (ed.), States’

or seats on the basis of race.18 These laws were first enforced by

Laws on Race and Color (Athens:

conductors and ticketing agents, whose duties included maintain-

University of Georgia Press, 1997).

ing segregated spaces; railroad companies could be fined as much

17 C. Vann Woodward and William S.

as $100 a day for violating segregation laws.19

McFeely, The Strange Career of Jim Crow

But Jim Crow legislation did not end there. By the time the

(Oxford University Press, 2001), 7.

18 Richard Henry Boyd (ed.), The Separate

United States entered into the First World War, laws in Southern

or “Jim Crow” Car Laws (Nashville:

states ordered racial segregation in marriage, education, and

National Baptist Publishing Board,

health care. Laws also molded the shape of daily life in other ways,

1909), 6.

as state and local prohibitions prevented different races from rent-

19 North Carolina Railroads (ch. 60, art. 12,

ing in the same building and required that movie theaters seat the

secs. 94-98, inclusive; secs. 101 and 103,

and 135-37, inclusive).

races separately, that amateur baseball teams play on diamonds

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 2 Spring 2012

45

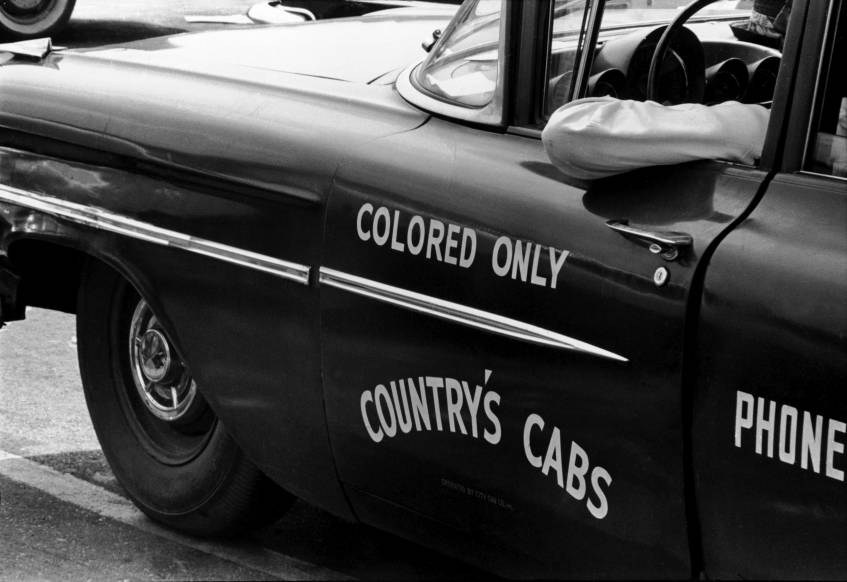

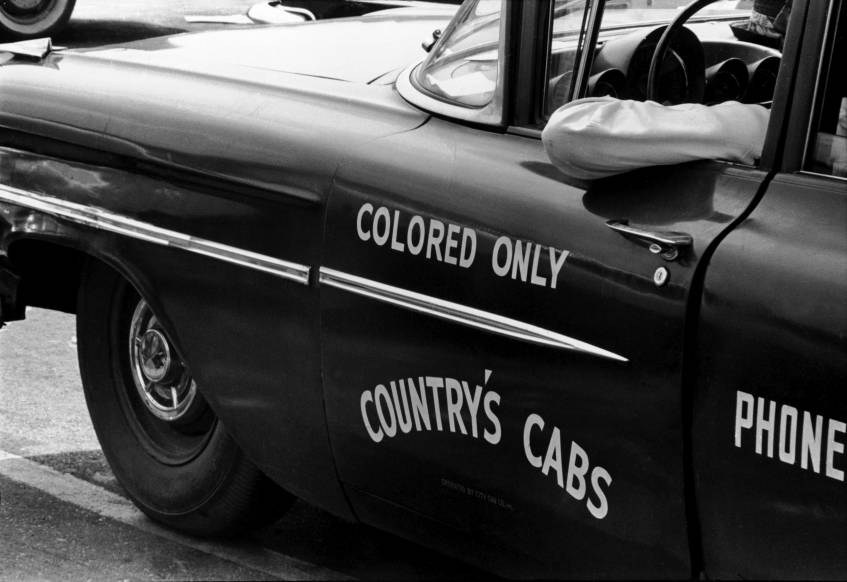

Figure 3

separated by two or more blocks, and that restaurants instal parti-

Danny Lyons, Segregated Taxi, Birmingham,

tions at least seven feet high between areas reserved for white and

Alabama, 1960, Magnum Photos, NYC16911.

non-white diners.

In the post-Civil War South, reformers argued that trans-

portation, education, and infrastructure would transform this

impoverished region. Little did they anticipate, however, that the

very trains, street cars, parks and hospitals that these reformers

helped introduce and develop would become part of complex

systems of racialized wayfaring. The rapid growth of cities like

Atlanta shows just how closely Jim Crow segregation followed

Southern urbanization. This emblem of the New South also

became one of the most segregated cities in the nation. Jim Crow

became the very public face of new civic ordinances that extended

not only to public spaces under the city’s jurisdiction (e.g., parks

and libraries), but also to privately-owned ones like saloons and

restaurants. Legislation mandated that black barbers could not

cut the hair of white women or children under 14, and separate

Bibles were required for white and black witnesses in the Atlanta

court system. In cities like Atlanta and Birmingham, taxis had to

be labeled by race “in an oil paint of contrasting color,” and laws

stipulated that drivers had to be the same race as their customers

(see Figure 3).20

Separation of Public Space in the New South

For whites and blacks, most day-to-day activities in the American

20 Woodward and McFeely, 116.

South were carried out in racialized space. Mark Schultz notes,

46

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 2 Spring 2012

however, that race relations in the rural (as opposed to urban)

South were marked by a “culture of personalism,” which shaped

racial interaction on the basis of close relations and custom, rather

than on the law.21 In these settings, Jim Crow space was rarely

labeled; tradition alone, for instance, clearly dictated that blacks

were to step aside for passing whites on a sidewalk. Many small

towns enforced Saturdays as “Black People’s Day,” when town

business districts were given over to weekly shopping trips by

African Americans flush with Friday paychecks. County fairs

often sold tickets marked “colored” to African Americans, and

they would be open to whites on Tuesdays through Fridays, thus

leaving Saturdays for blacks. Wilhelmina Baldwin, a teacher from

Waynesboro, GA, remembered that the entire town became white

after dark: “They also had a curfew for blacks. If you were just a

run-of-the-mill black, your curfew was at 9:30. If you were, you

know, what they called an educated black, you could stay out ‘til

10:30. If you stayed out beyond 10:30, you had to have a written

statement from the chief of police.”22

Because race relations were relatively settled in less densely

populated rural and farming districts, wayfinding systems in these

areas were often unnecessary. Most residents living in these small

communities were born there, and few feared getting lost, either in

physical or social terms. Outsiders who stumbled into small and

often isolated towns could read the unwritten signs that signaled

segregation. George Butterfield, an African-American Supreme

Court judge and then congressman in North Carolina, noted that,

“when you live in the South and have been in the South all your

life, you could find [places to eat and sleep] instinctively.“23

Nevertheless, as the towns and cities of the new urbanized

South grew, residents encountered unfamiliar problems; here,

where strangers could casually meet and interact, traditions were

not established. Complex racialized spaces had to be negotiated,

and expectations for behavior had to be articulated. Restaurants

frequently erected wood screens through their dining rooms, and

21 Mark Schultz, The Rural Face of White

train cars were sometimes designed with panels that divided

Supremacy: Beyond Jim Crow (Urbana:

carriages into two distinct compartments; in a Virginia courthouse

University of Illinois Press, 2005), 6.

22 Wilhelmina Baldwin, Duke University

and along a South Carolina swimming shore, ropes separated the

archive. See also James W. Loewen,

black and white sections of the court and the beach.24 And, as archi-

Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of

tectural historian Tim Weyeneth has demonstrated, large-scale

American Racism (New York: The New

building projects increasingly dictated the terms and conditions of

Press, 2005).

racialized space25 as specifically-designed schools, libraries, hospi-

23 George Kenneth Butterfield, oral history

tals, mental hospitals, homes for the aged, orphanages, prisons,

interview, July 19, 1994, Behind the Veil

project, use tape 12, tray C, Tuskegee,

and cemeteries were built across much of the South in the first half

AL., Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special

of the twentieth century. In Richland County, SC, for instance, the

Collections Library, Duke University.

1940s remodeling of Columbia Hospital by Lafaye and Associates

24 Weyeneth, 21.

included the construction of a smaller, separate hospital two blocks

25 For more on exclusion in Southern

away from the main, whites-only complex.26 When building such

architecture, see Weyeneth, 13-15.

26 Weyeneth,16.

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 2 Spring 2012

47

completely separate spaces was deemed too costly or otherwise

inefficient, structures were commonly designed to include both

separate and shared spaces under a single roof. Hospitals, for

instance, would have segregated wings, public housing would be

divided into separate districts or even units, and public parks were

fenced or roped into grounds and facilities designated as “white”

or “colored.”

Although no urban planner designed fully segregated

cities, architects clearly planned buildings that not only included

separate black and white spaces but also ensured segregated

routes for finding those spaces. For example, architectural draw-

ings of cinemas designed by Erle Stillwell in North Carolina,

reveal not only separate African-American seating areas but also

careful y planned systems of diversions, including entrances (for

a similar configuration, see Figure 1), and passageways explicitly

designed to lead non-whites away from white-designated spaces.27

When Stil wel designed Raleigh’s Ambassador Theater in 1938,

27 Going to the Show (www.docsouth.unc.

he planned for African Americans to enter the building at a side

edu/gtts) is a digital library project that

entrance. Patrons climbed a discrete staircase that led them to a

documents and illuminates the experi-

landing housing what Stillwell’s plans called the “colored” box

ence of movie-going in North Carolina

between 1896 and 1930. It should be

office. Up another flight of stairs, African Americans could find

noted that women, too, were segregated

toilets, a small room for the use of “colored ushers,” and balcony

from men in a similar way. And, as

seats.28

Elizabeth Abel notes in “Bathroom Doors

Although the Ambassador Theatre was torn down in 1979,

and Drinking Fountains: Jim Crow’s

the relatively complex passage by which African Americans entered

Racial Symbolic,” Critical Inquiry 25

(Spring 1999): 448, court rulings “endors-

the movie house from the street, then found the “colored” box

ing separate car laws often cited gender

office, then found their seats and separate facilities suggests just

separation as a model for racial segrega-

how byzantine Jim Crow wayfinding could be. Recalling a less

tion.” For example, the state Supreme

carefully planned theater in Waynesboro, GA, Wilhemina Baldwain

Court of Pennsylvania cited the analogy

described exiting a matinee showing of a film in the late 1930s;

of the ‘ladies’ car,’ which is ‘known upon

white patrons insisted on not even seeing African Americans who’d

every well-regulated railroad’ and whose

‘propriety is doubted by none.’”

attended the same show. “There was usually nobody there. We’d

28 The pressure to accomplish this separa-

go to the ticket window, buy our tickets, and go upstairs (to the

tion was clear; as a point of pride, many

segregated seating for blacks). And likewise there was nobody

theaters explicitly advertised themselves

there when we would come out. Well, one day there was a little

as “white” theatres. Those theaters

white boy. . . eight or nine years old. . . he was standing there, with

that did admit blacks rarely stated so,

but even they abided by norms of racial

his hands across the door. . . and so when we got to the bottom of

segregation. If provided at all, seat-

the steps I said ‘excuse me please.’ He said ‘Niggers can’t come out

ing for African Americans was usually

till the white people get out.’” At least a decade older than the boy,

relegated to theater balconies; railings or

the movie-going Baldwin talked the boy down but recalled seeing

other barriers were commonly installed

other African Americans obeying his directions.29

to separate shared balconies. For more,

Blocked doors, the construction of isolated buildings and the

see Robert Allen, “Going to the Show:

Mapping Moviegoing in North Carolina,

erection of barriers were useful but only effective for a limited time

Documenting the American South,

to segregationists. Similarly, duplicate architectural features such as

http://docsouth.unc.edu/gtts/index.html

entrances, exits, elevators, and stairwells, might have served imme-

(accessed November 27, 2010).

diate racist ends. However, if they lacked specific labels to indi-

29 Oral History Interview with Wilhelmina

cate their function, such structural elements lost their significance.

Baldwin, July 19, 1994, use tape 12, tray

C, Tuskegee, AL, Behind the Veil project.

48

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 2 Spring 2012

When President Franklin Roosevelt inspected the construction of

the Pentagon in Arlington, VA in 1941, he questioned the inclu-

sion of “four huge washrooms placed along each of the five axes.”

The astonished president, a native of New York, was informed

that Virginia’s segregationist legislation “required as many rooms

marked ‘Colored Men’ and ‘Colored Women’ as ‘White Men’ and

‘White Women.’” Military officials, heeding larger issues of waste

and inefficiency, ultimately disregarded the local law; signs were

never mounted on the doors and the duplicate spaces lost their

initial meaning.

Finding the Way to Jim Crow Space

While Arthur and Passini suggest that wayfinding is a form of

spatial problem-solving, they insist that successful wayfinding

systems do not rely on architecture or barriers alone; instead, they

require the consistent identification and marking of space. Without

signage, the Pentagon’s Jim Crow bathrooms lost their mean-

ing. Reading the plans of Raleigh’s Ambassador Theater, with its

carefully designated “colored box office” and room for “colored

ushers,” makes clear how the architect created a labyrinth of

passageways that guided African-American customers away from

whites. But without labeling, the theater’s maze of passageways

would have been incomprehensible.

As a field, wayfinding was in its infancy when Jim Crow

laws and signs were at their height. However, as the older Jim

Crow signs make clear, by the early twentieth century, public

signage could construct complex systems when supported by

custom and law. Of course, segregation was so pervasive a system

that whites also abnegated a degree of freedom by embracing it.

They, too, arranged their shopping around “black days” in town

and avoided taking colored taxis. Jim Crow signage dictated both

white and black space. The white writer and sociologist Kathryn

DuPre Lumpkin recalled, “as soon as I could read, I would care-

fully spell out the notices in public places. I wished to be certain

we were where we ought to be. Our station waiting rooms—‘For

Whites.’ Our railroad coaches—‘For Whites.’” White passengers

could be ejected from trolleys and buses when they chose to sit in

the back rows. Jennifer Roback, for instance, points to the case of

J. M. Dicks, a white Augusta, GA ironworker who violated state

segregation ordinances by insisting on sitting in the back of a street-

car in May 1900. Arrested by the train’s conductor, Dicks explained

to the court “When I got off from work yesterday afternoon I was

feeling tough and looking tough. . . . I saw some ladies up ahead

and did not want to sit by them looking like I was.”30 Calling the

conductor a “d--- fool,” the passenger was faced with a perplexing

30 Jennifer Roback, “The Political Economy

situation: violating social custom on the one hand or transgressing

of Segregation: The Case of Segregated

the law on the other.

Streetcars,” The Journal of Economic

History 46 (December 1986): 902.

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 2 Spring 2012

49

Despite the limits that also affected them, whites—especially

men—were often accorded a degree of flexibility in infringing on

segregated spaces. For example, where African Americans were

strictly prohibited from whites-only passenger cars on trains, the

colored cars could double as smoking cars (for whites) or as spaces

where the white crew could lounge and relax. Ticketed white

passengers could pass through the Jim Crow cars, but African-

Americans were often prohibited from walking through those set

aside for whites. Indeed, public space was often deemed “white”

by default, unless otherwise designated.31

Even when signage clearly circumscribed white behav-

ior, the legal system often treated white’s infractions lightly. For

instance, when a municipal judge heard the case of J. M. Dicks,

the Augusta, GA ironworker who insisted on sitting in the colored

section of a city street car, the judge publicly belittled the conduc-

tor and arresting officers for their lack of judgment and dismissed

the case.32 Jim Crow signs dictated the decisions and actions of both

black and white Southerners, but there was no doubt who ulti-

mately held power in these situations.

Decision-Making in a Jim Crow World

Especial y for African Americans, finding the way to one’s “own”

space in the Jim Crow South clearly could be a complex and coun-

ter-intuitive process. However, failing at it also carried high stakes.

While theorists today describe wayfinding as a process that can

keep people from being lost and afraid, in the Jim Crow South,

mistaking a turn or using the wrong facilities could result in

violence or death.

Passini suggests that wayfinding involves a hierarchy of

decision making that begins long before an individual starts to

move through space. Choosing a destination—that is, deciding

to move from point A to point B—is a high-order decision. The

scale of the trip is unimportant; the resolutions to shop at a store

31 As Tim Weyeneth notes, “much of the

down the street or to take a trip across the country both reveal

time signage was unnecessary because

that a high-order decision has been made. In the South, the very

white space was commonly recognized

choice of where one could and could not go was complex; a host of

and acknowledged by both races. The

white university and the white library

semi-public spaces (e.g., white churches, beauty parlors or funeral

had no need to post a sign. No black man

homes) were simply off limits to blacks. Indeed, most African

traveling to a southern city would seek to

Americans in the rural South relied not only on signs but also on

stay in its major hotels. In a small town

a series of learned codes of conduct, habituated through years of

everyone knew that the white doctor

living in racialized space and passed from one generation to the

did not welcome black patients into his

next. This learning was part of what black activist and academic

office.” Weyeneuth, 14.

32 As a municipal judge, the magistrate

Cleveland Sellers calls a “subtle, but enormously effective, condi-

who heard the case insisted that he

tioning process. The other people in the community, those who

didn’t have the authority to enforce the

knew what segregation and Jim Crow were all about, taught us

state-wide segregation law (Augusta at

what we were supposed to think and how we were supposed to

this time was working on a city ordinance

to the same effect, but it was still in

proposal stages). Roback, 902-3, note 25.

50

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 2 Spring 2012

act. They did not teach us with words so much as they taught us

with attitudes and behavior. There wasn’t anything intellectual

about the procedure. In fact, it was almost Pavlovian.”33

As an early, if incomplete, form of wayfinding, the Jim Crow

spatial system complicates Passini’s theory. In his view, wayfind-

ers make high-order decisions in a sociological vacuum; but unlike

Passini’s empowered wayfinders, African Americans who under-

stood the shaping of Jim Crow space automatically formed their

higher order decisions around Jim Crow exclusion. Certain desti-

nations were automatically off limits; others were simply avoided.

Remembering these limitations, Wilhemina Baldwin recalled how

her parents shielded their children, avoiding taking them to public

spaces dominated by whites. “There were just certain things that

we did not do,” she recalled. “For instance, going to wherever

we went out of town, they took us. We never had to go to the bus

station for anything. Until I got to be 10 years old, they didn’t

take me to buy shoes. They bought my shoes. And if they didn’t

fit, they’d take them back and get another size. They bought the

clothes for all of us like that. So we didn’t get into the stores to have

to deal with the clerks and whatnot.”34

Planning Action in Jim Crow Spaces

African Americans in the Jim Crow South might have practiced a

highly selective decision-making process, but as Passini reminds us,

wayfinding involves more than choosing where to go. Having fixed

a destination, the wayfarer then begins executing a series of lower

level decisions that make that action possible. For most wayfar-

ers, this planning involves designating a route and developing

an action plan. Again, African Americans chose their routes with

care. Long distance car trips through the South were often experi-

enced as a gauntlet. African American wayfarers needed “exquisite

planning,” carefully weighing the need to stop for gas and food in

segregated gas stations and restaurants, and often driving for three

or four days without stopping, loading up on cold cuts and stuff-

33 Cleveland Sellers, The River of No

ing ice boxes and lard buckets ful of ice to provide rudimentary air

Return: The Autobiography of a Black

conditioning.35

Militant and the Life and Death of SNCC

(Jackson: University Press of Mississippi,

Even planning simple routes around one’s hometown could

1990), 10.

be fraught with peril, and many African Americans chose routes

34 Oral History Interview with Wilhelmina

that avoided white spaces altogether. As Ralph Thompson recalled,

Baldwin, July 19, 1994, use tape 12, tray

his parents warily planned his childhood visits to Memphis. His

C, Tuskegee, AL, Behind the Veil Project.

mother, for example, took elaborate precautions to sidestep the

35 Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other

“things that would be embarrassing, when they couldn’t fight back.

Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great

Migration (New York: Random House,

. . If we went downtown and they had the colored drinking foun-

2010), 196.

tain and white drinking fountain, my mother would always tell us

36 Ralph Thompson interview, Remembering

to drink water before we left home. So we didn’t get caught into

Jim Crow: African Americans Tell About

drinking water out.”36 Dr. Charlotte Hawkins Brown ran the Palmer

Life in the Segregated South, William H.

Memorial Institute, a missionary-funded school in Sedalia, NC, and

Chafe, Raymond Gavins, Robert Korstad

(eds.) (New York: The New Press, 2001).

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 2 Spring 2012

51

she taught her students to develop action plans that worked around

Jim Crow restrictions. Taking her students to the movies, for exam-

ple, she’d rent the entire cinema for the day and avoid the segre-

gated upper balcony.37 But no amount of careful planning could

erase the ubiquitous presence of the signs that shaped the very

environment in which African Americans lived their daily lives.

Wayfinding in Action: Lower Order Decisions

Indeed, in the Jim Crow South, signs were used to separate

the races on a limited, local level, room by room, seat by seat.

Segregation was most tangible when confronted in person, as a

wayfarer moved toward his or her destination. Moreover, even

if an African-American bus passenger momentarily mixed with

white passengers on a crowded platform, that passenger would

constantly remain aware of the larger spatial system intended to

eventual y isolate him or her in a specific section of the bus itself

or station.

According to Passini, a journey is begun with a high-level

goal but enacted by low-level decisions. Wayfaring, compris-

ing simple actions like “walk down the hall” or “open this door,”

combines observation of local features (e.g., stairs and doors) with

previous acquaintance with a space (e.g., earlier instructions or

consultations with a map or guide). As Reginald G. Golledge notes,

this navigation can be a “dynamic process;” as the wayfarer absorbs

information from the environment, his or her original action plan

is “constantly being updated, supplemented, and reassigned.”38

Finding one’s way through streets and intersections or corridors

and stairs may seem relatively simple; for most wayfarers, deciding

what turn to take or which stair to follow, or choosing whether to

continue or to stop and acquire information from the environment

is clear and negotiated with relatively little thought. Navigating a

route in the Jim Crow South, however, required African Americans

to maintain constant vigilance.

Jim Crow signs exerted their most devastating power at

precisely this level, consistently challenging and deflecting African

Americans’ action plans. Indeed, higher level destinations could

be chosen while knowing where one would and would not be

welcome. However, confronted with “white only” trains and wait-

ing rooms, African-American wayfarers were faced with immediate

lower level decisions. Segregation signs in the South filled multiple

roles, but in wayfinding terms, they can be broken into two general

37 Charles Weldon Wadelington, Charlotte

types: identification signs and directional signs.

Hawkins Brown and Palmer Memorial

Institute: What One Young African

Identification Signs

American Woman Could Do (Chapel

Often called “the building blocks of wayfinding,”39 identification

Hill: University of North Carolina Press,

signs mark out spaces by displaying their name or their function.

1999),186.

Since the mid-nineteenth century, in rapidly growing cities like

38 Golledge, 7.

39 Ibid., 48.

New York and London, public signage proliferated, labeling space

52

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 2 Spring 2012

and addressing passersby.40 Simple labeling techniques (e.g., posted

street names and addresses, room numbering signs, name plates,

and other forms of labeling) became ubiquitous in the United

States after the Civil War. But the marking of Jim Crow space was

more specific and relied on fairly consistent terms of identification.

Clearly understood labels like “colored only” and “whites only”

were most common, although some relied on more cursory words,

such as “white” or “black.” Such signs routinely rerouted travelers.

Directional Signs

Coupled with exclusionary phrases, like “Whites This Way” or an

arrow with the words, “Colored Dining Room in Rear,” Jim Crow

signs not only identified, but also directed. Usually mounted on

walls or placed overhead, directional signs dictated who could

drink at which water fountain or where to sit in a restaurant (see

Figure 4).

These directives could also be complex, involving a sequen-

tial process of multiple decisions, such as entering a train station

through the “right” door, buying a ticket at the “right” window,

finding the “right” waiting room, moving from that waiting room

to the “right” platform, then finding the “right” train car. At this

time, signage systems meant to control behavioral actions (e.g.,

turning left or going up stairs) were still in their infancy. But

simple graphic prompts, such as prominent arrows or the Victorian

letter jobber’s pointing finger, or manicules still had the power to

shape decisions.41

Jim Crow Laws as Signage: Substance and Make

The Jim Crow system may seem monolithic today, but it was

actual y held together through a patchwork of legislation, and it

varied not only from state to state, but even from town to town.

40 David Henkin, “Word on the Streets:

While individual signs could convey an indisputable authority, it

Ephemeral Signage in New York,” The

took time for them to develop a consistency that would resemble

Nineteenth-Century Visual Culture

a careful y planned wayfinding system developed by designers.

Reader (New York: Routledge, 1994), 195.

Essential y, segregation signage fil ed multiple functions; at once,

41 Gillian Fuller, “The Arrow—Directional

it indicated the existence of laws intended to guide individual

Semiotics: Wayfinding in Transit,” Social

Semiotics 12 (2002): 231.

behavior, it educated both whites and blacks about where they

42 Acts of Tennessee, Chapter 10 No. 87.

should and should not be, and it served as references for train

43 Laws of Mississippi, 1904, Chapter 99:

conductors, police officers, and other authorities in case of confu-

4060.

sion. Some Jim Crow legislation specifically called for signage

44 For example, in order to “promote

to be instal ed and these statutes often dictated such particulars

comfort on streets cars,” a 1905

Tennessee law, authorized “large” signs

as the size of the lettering, the medium, and the placement. For

to be kept in” a conspicuous place,” (Acts

example, to “promote comfort on street cars,” a 1905 Tennessee

of Tennessee, Chapter 10 No. 87). Some

law, authorized “large signs shall be kept in a conspicuous place,”42

laws were even more specific. A 1904

meanwhile, a 1904 Mississippi law ordered street car signs to be

Mississippi law, for instance, ordered

8x12 inches in size.43 While legislation sometimes dictated particu-

the size of street car signs to be eight by

lars in this way,44 implementation was often left to municipalities,

twelve inches high (Laws of Mississippi,

1904, Chapter 99, 4060).

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 2 Spring 2012

53

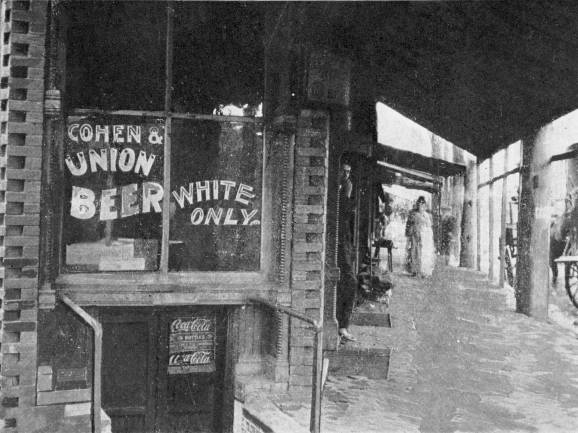

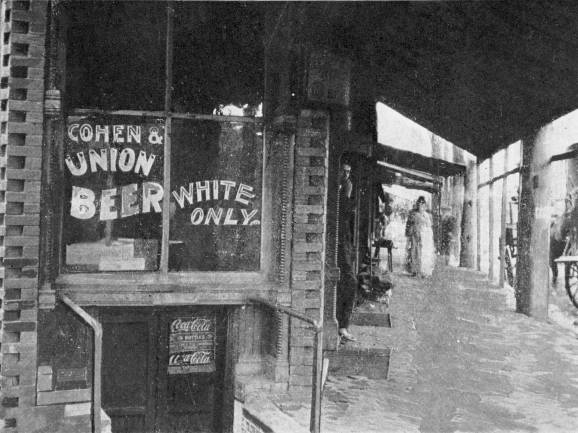

Figure 4

Anon. Showing how the colour line was

drawn by the saloons at Atlanta, Georgia.

1908, Courtesy of The New York Public

Library. www.nypl.org.

local transit authorities, or individual business owners. It was not

uncommon for individuals to go beyond the law by creating and

placing signs on an ad hoc basis; for instance, no state or local law

regulated the race of patrons using a Coca Cola machine at a sport-

ing goods store in Jackson, TN, despite its being marked “White

Customers Only!”45

Although Jim Crow signage clearly was part of an elabo-

rate system that created separate Jim Crow spaces, the signs that

made up this network varied in style and content; indeed, where

wayfinding devices today aim to be uniform and predictable, Jim

Crow signs were stylistical y diverse. Dating from a period when

graphic design was still coalescing as a self-identified profession,

individual designers or firms were rarely associated with these

communications. Initial y Jim Crow signs were often the work of

local or itinerant sign painters or skil ed itinerants whose work

included advertising murals and lettering on shop windows and

vehicles. Many of these signs reflect their painters’ pride in their

craft; Jim Crow signage often includes decorative flourishes and

other embellishments that seek to anesthetize the regulatory

message. For example, the decorative sweeps and italicization

of an Atlanta saloon sign from 1908 reflects a degree of elegance

often displayed in late Victorian signage (see Figure 4); in this case

the sign tries to integrate “white only” with the business’s name,

“Cohen & Union Beer.” Similarly, a 1939 photograph of the sign

for “The Gem Theatre: Exclusive Colored Theatre” reveals an orna-

mental italic subscript that reinforces both its Anglicized spel ing

“Theatre” and preferential description “Exclusive” (see Figure 5).

In both these cases, the aestheticized letterforms seem to be an

attempt to mask the blow of segregation by “prettifying” it, domes-

45 See Library of Congress, Prints and

ticating it, or at least making the regulatory message more palat-

Photographs Division, Visual Materials

able. The politesse of a hand-lettered sign on a North Carolina

from the NAACP Records. Call LOT

13087.

54

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 2 Spring 2012

Figure 5

Russell Lee, Gem Theatre Sign, Waco,

Texas, 1939, Courtesy of the Library of

Congress U.S. Farm Security Administration/

Office of War Information, Prints &

Photographs Division, Library of Congress,

LC-USF33- 012498-M2.

Figure 6

Jack Moebes, Jim Crow sign being removed

from a Greensboro, NC bus, in response

to a court ruling, 1956. Copyright Jack

Moeges/Corbis.

bus read “NORTH CAROLINA LAW/White Patrons, Please Seat(sic)

From Front/Colored Patrons Please Seat(sic) from Rear/NO SMOKING”

using an italic script to suggest an effort at elegance that matches

the decorous use of “please” (see Figure 6). In some African-

American owned establishments, however, such signage could be

cursory and grudging. A haphazard col ection of signs hanging on

a mixed-use living quarters and juke joint for migratory workers

in Bel e Glade, FL, for example, includes one clearly hand-painted

sign stuck off to the side, reading “COLORED ONLY,” fol owed by

the phrase “POLICE ORDER” (see Figure 7).

Institutionalization and Mass Production

In the early years of Jim Crow signage, the use of ink and paint was

sometimes legally stipulated; an 1898 Tennessee law, for instance,

insisted that such signs not only be placed in a “conspicuous

place,” but that they be painted or printed.46 Widespread demand

ultimately led to the mass manufacture of Jim Crow signs, and

46 Acts of Tennessee, Chapter 10 No. 87.

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 2 Spring 2012

55

Figure 7 (left)

by the 1940s, such signs were standard retail products commonly

Osborne, “Colored Only: Police Order,” Belle

available at national chains (e.g., Woolworth’s and Western Auto),

Glade FL, 1945, Copyright/Corbis.

as well as at local home supply and hardware stores throughout the

South. The manufactured signs were quite different from the hand-

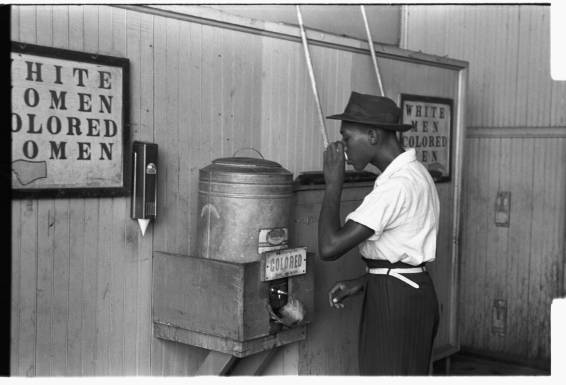

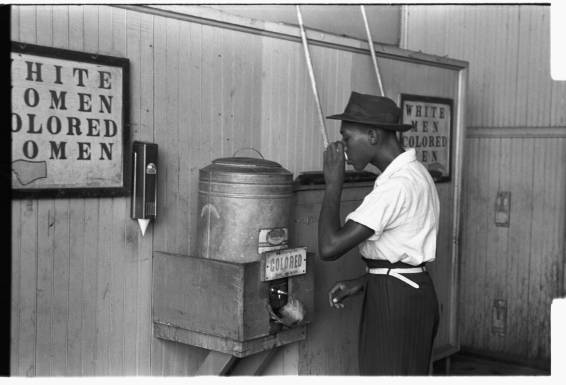

Figure 8 (right)

Russell Lee, “Man drinking at a water cooler

drawn and -painted signs of a generation earlier, tending toward

in the street car terminal, Oklahoma City,

the utilitarian rather than the decorative; they were more matter-

Oklahoma,”1939, Courtesy of the Library of

of-fact rather than persuasive (see Figure 8). Moreover, as wayfind-

Congress U.S. Farm Security Administration/

ing devices, they were not as descriptive and provided less explicit

Office of War Information, Prints &

directions for users. William Kennedy, a journalist for the Pittsburgh

Photographs Division, Library of Congress,

Courier, reported from Jacksonville, FL in 1961, that “best sellers”

LC-USZ62-80126.

were the “catch-all plain race labels, which could be tacked on any

door” and simply read “white” and “colored.”47 While most manu-

factured signs were produced with standard industrial printing

processes, including offset lithography and silkscreen, Jim Crow

signs were also customized with stencils and vinyl letterforms and

were printed on more permanent materials, including metal and

porcelain. At the new Tennessee Valley Authority headquarters,

for instance, an imposing “WHITE” sign was crafted in metal and

installed above public water fountains, conveying a tangible sense

of institutional authority. While the sans serif letters were clearly

influenced by the spare, unadorned typographic forms of the emer-

gent Modernist movement, their function was utterly antithetical

to the egalitarian, even utopian, goals that drove designers such as

Jan Tschichold and Herbert Bayer to develop typefaces that would

promote universal legibility.

The tradition of hand-made, and especially painted, Jim

Crow signs continued until the Civil Rights movement obvi-

ated the entire system in the early 1960s. Nevertheless, as mass-

produced signs became more and more common, the increasing

consistency of segregation signs’ appearance began to convey

a kind of uniform identity, flatly assigning races to different

47 William Kennedy, “Dixie’s Race Signs

spaces. Nevertheless, this increasing uniformity was misleading:

‘Gone with the Wind,’” Reporting Civil

the South’s segregation laws and customs were inconsistent and

Rights 1 (New York: The Library of

America, 2003), 627.

56

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 2 Spring 2012

inconsistently applied; in addition, the signs’ authoritative appear-

ance belied a system of racializing space that, while pervasive, was

far from universal y understood.

Ambiguous Spaces and Incomplete Wayfinding Systems

Jim Crow segregation differs from latter-day wayfinding in several

notable ways. While Passini defines wayfinding as “essentially

congruent with universal design” and a formal desire for inclu-

siveness, Jim Crow signage was dictated by racial exclusivity.48

Moreover, the Jim Crow system was held together through a

diverse hodgepodge of legislation that varied not only from state

to state, but even from town to town. The patchwork of laws

was essentially reflected in the many different forms of graphic

expression; the style, content, and materials used to make Jim

Crow signage were wide-ranging. There was no consistent look

to the signs until they began to be mass-produced. Finally, no

one “designed” Jim Crow signs; indeed, the earliest signs predate

modern notions of design and designer.

Not surprisingly, Jim Crow space was piecemeal and

fraught with inconsistency. Some spaces (e.g., city sidewalks)

proved impossible to formal y regulate; rarely, if ever, was specific

behavior or action in these areas dictated by signs. Similarly,

while crowded train and bus depot platforms frequently included

numerous “white” or “colored” signs designed to instill order in

the spatial and social chaos, these spaces were often fluid, evok-

ing both spatial and racial confusion. Indeed, the wayfinding signs

sometimes added to the system’s inherent dysfunctionality. Easily

destroyed, moved, obscured from view or lost, the signs were

anything but permanent, and the spaces they were designed to

regulate remained transitory and amorphous rather than strictly

defined and demarcated.

Some Jim Crow signs were even designed to serve dual

purposes. Despite legal requirements to provide separate facili-

ties for both races, some impoverished Southern towns could only

purchase a single public water fountain; by default, such amenities

were marked with a “whites only” sign. As Lillian Smith observed,

however, “sometimes when a town could afford but one drinking

fountain, the word White was painted over one side and the word

Colored on the other. I have seen that. It means that there are a few

men in that town whose memories are aching, who want to play

fair, and under ‘the system’ can think of no better way to do it.”49

48 Romedi Passini, “Wayfinding Design:

Principal flashpoints of racial tension were the street cars

Logic, Application and Some Thoughts

on Universality,” Design Studies 17

and trolleys that ran in larger Southern cities in the late nineteenth

(1996): 319.

century; as the journalist Ray Stannard Baker noted, what made

49 Lillian Smith, Killers of the Dream,

them volatile spaces was the “very absence of a clear demarca-

(New York: W. Norton, 1994 reprint of

tion.”50 Streetcar interiors created what he called a racial “twilight

1949), 95.

50 Ray Stannard Baker, Following the Color

Line, American Magazine (1908): 30-1.

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 2 Spring 2012

57

zone.” Rather than run two sets of trolleys at great expense, trans-

portation authorities often followed the letter of the law by segre-

gating the interior space of each tram. Local laws, such as the

one established in 1900 in Augusta, GA, stipulated that African

Americans must first fill seats in the rear of a car, while whites were

to sit in the front seats. Although the first two seats of each car were

reserved for exclusive use by whites and the last two seats reserved

for blacks, the undefined middle zone was segregated according

to the capacity of any given car and its relative use at any given

time.51 In response, ”white” or “colored” signs were often hung on

strips and slid along the length of the car; if trolleys were crowded,

many municipalities empowered conductors to determine the loca-

tion of the car’s “middle” and to allocate seats accordingly. Indeed,

conductors were often legally provided with the power to arrest

and otherwise enforce their temporary regulations.

This movable streetcar and later bus signage created an

unstable space that became a flashpoint for racial conflicts, result-

ing in fights, arrests, and even death.52 To illustrate, in 1917, African-

American members of the U. S. Army’s 24th Infantry Battalion

were ordered from Columbus, NM, to Houston, TX. Fearing the

onslaught of large numbers of negro troops, local politicians tight-

ened segregation. When the soldiers arrived in the city, however,

they simply ignored the Jim Crow signs hung in movie theaters and

street cars. At times they tore the signs down and at least once, at

a local dance, made them objects of ridicule by wearing them; their

anger at Houston’s ordinances percolated into a full-scale mutiny

by August 1917.53

Such uprisings occurred throughout the South. In a single

year, beginning in September 1941 and ending 12 months later,

at least 88 cases occurred when blacks occupied “white” space on

public transportation in Birmingham, AL.54 After the war, men,

51 Jennifer Roback, “The Political Economy

particularly African-American veterans returning from active

of Segregation: The Case of Segregated

duty—more actively resisted these signs. In 1946 in Alabama,

Streetcars,” 901.

a black ex-Marine removed a segregationist sign from a trol-

52 Carol Anderson, Eyes off The Prize: The

ley; in the resulting melee, he was shot dead by the local chief of

United Nations and The African American

police.55 As late as 1956, just as Jim Crow travel restrictions were

Struggle for Human Rights, 1944-1955

(New York: Cambridge University Press,

being lifted from interstate travel, Jet Magazine announced the

2003), 58.

death of Robert L. Taylor, a 30-year-old veteran from Ohio, who

53 Arthur E. Barbeau and Florette Henri,

dared to use a whites-only restroom on a speeding train in central

The Unknown Soldiers (Cambridge: Da

Tennessee; Taylor’s body was found the next day beside the train

Capo Press, 1996), 28.

tracks.56 At best, Jim Crow wayfinding was based on a rigid race-

54 Robin D.G. Kelley, “’Not What We Seem’:

based caste system; for soldiers who’d experienced spatial freedom

Black Working-Class Opposition in the

Jim Crow South,” Journal of American

in the North, the West, or overseas, the extent to which it shaped

History 80 (June 1993): 75-112.

the lives of African Americans and their day-to-day movement

55 Anderson, 58.

was inexcusable.

56 ”A Fear That a Negro Ohio War Veteran,

Robert Taylor, Was Slain for Using

White Toilet on Tennessee Train,” Jet

Magazine, January 5, 1956.

58

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 2 Spring 2012

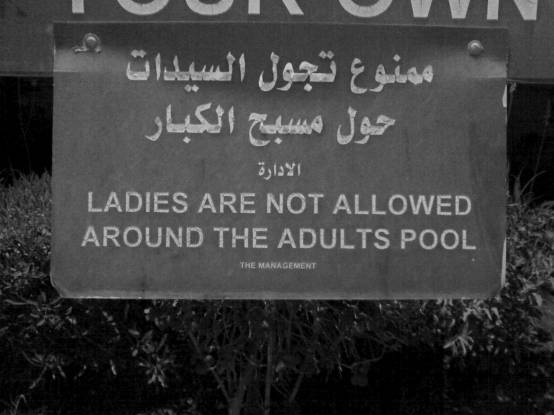

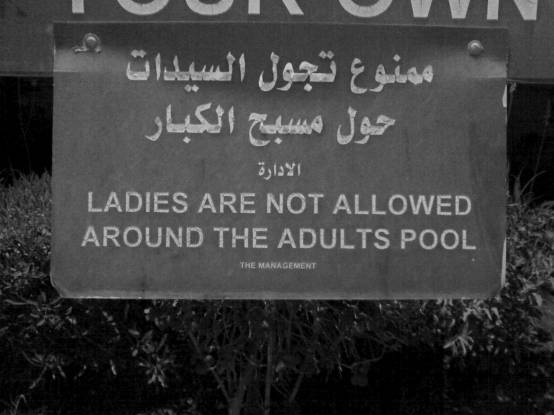

Figure 9

Ladies are not adults, photo by Eric Bruger,

used under the Share Alike license of Creative

Commons. Photograph URL: http://www.flickr.

com/photos/uw-eric/3182483073/

Ending Jim Crow Signs

When Rosa Parks famously refused to give up her seat on a

Montgomery, AL, bus to a white man in 1955, she sat in the bus’s

fifth row—officially the beginning of its colored section but also one

of the ambiguous “twilight zones” that a conductor might trans-

form from “black” space to “white” space by simply repositioning

a printed sign. Her act of civil disobedience reflected the increas-

ing questioning of Jim Crow segregation and the system it repre-

sented by both whites and blacks. Indeed, Parks’ action was well

timed; after 1946, when the Supreme Court’s decision in Morgan v.

Virginia ruled segregation illegal on interstate bus travel, Jim Crow

laws were increasingly challenged at the local level.

In considering the system under the rubric of wayfinding,

defined as spatial problem solving, a critical need is to identify just

whose problems wayfinding actually addresses. For the whites

on Parks’ bus, Jim Crow signs directed African Americans away

from white space, thus perpetuating a sense of racial entitlement.

Of course, this study of Jim Crow signs as wayfinding signals is

more than a historical exercise in remembering the forgotten past

and more than a theoretical exercise in overlaying the two systems.

More critical y, this study is intended to prod us to consider more

recent wayfinding systems that perpetuate similar entitlement. In

South Africa, for instance, racialized wayfinding was explicit and

careful y control ed during that country’s long-standing system of

apartheid. Meanwhile, in other countries, most notably in Saudi

Arabia today, gender-specific wayfinding systems continue.

Whether applied to hotel gyms and pools which are off-limits to

women, or McDonald’s restaurants, which are restricted to women

and families, the Saudi kingdom has shaped a complex system of

spaces for women and aims to guide them toward it (see Figure 9).

Segregation signs not only point to separation in public space; they

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 2 Spring 2012

59

also serve as reminders that both law and signage are “designed”

and that “designers” have a role to play in thinking critical y about

their purpose. We have no record of what figures like Aicher and

Lynch made of the Jim Crow system; in some ways, this system

might have been the underbel y of or the precursor to the univer-

sal signage and systems that began to develop just as the segre-

gation system was being dismantled. In modern public spaces,

strangers can meet and mix in an informal manner. Traditional

mores are no longer relevant and residents must be guided

through unfamiliar spaces.

The most pervasive designed systems are often invisible

to those who follow them; if Sheila Florence simply assumed that

segregated racial spaces were “just the way it was,” she would

never have reflected on the powers that shaped Jim Crow signs.

Signage systems have hardly disappeared; but for designers today,

the fundamental issue is not just in noting them or designing them

from a disconnected, disinterested position. The real question

is about how well we know our own spaces and the power that

resides in them.

60

DesignIssues: Volume 28, Number 2 Spring 2012